Mike says that to hear the tale of my 50 years of solitude is to fall into a Garcia Marquez trap of twisted plots, dubious characters, catastrophes, and triumphs — minus the comedy. That’s my husband, the reader. I, the artist, sometimes look at my improbable life as if I were a figure stretched out across the surreal, cinematic canvases that are my signature.

Fifty is a bit of a stretch. I’m really 48, I think, but I’ve embraced 50 for some time now, probably starting around 45.

I am known as Balbir Krishan, though I’ve had other names. I am from and of the Jaat farming villages of western Uttar Pradesh. I was born at home and my family called me Ballu. Five years later, at my first day of school, the teacher scoffed at the unlikely appellation and told me that my name, henceforth, would be Balbir. Just like that, the name was scratched into the attendance register and across all the years of my life.

Here is the story that shaped me. It begins in heaven, drops like a rock into hell, and only much later finds its way to earth, where I can claim to be a reasonably well adjusted out gay man. So, if within my story is impenetrable pain, there is magnificence too, and between the lines, everything else. There are details far harsher than I can narrate here. They will wait for another time. They’re not going anywhere.

Not to see the hunger, hope, and lust for life underlining my story would be a serious omission. I always wanted to live, even when I lay down on the railroad tracks at age 22 and lost my legs. I may not have survived with my entire body, but today I am alive, with my mind and all my senses intact. I am able to feel happiness and I know how to love. My husband Mike doesn’t believe in fortune — good or bad, but he says that if he had to believe in a miracle, that would be it.

Early childhood as Ballu was idyllic. I farmed our fields with my father, took care of the family buffalo, and swam with playmates in the canals. Friendly people patted me on the head and pinched my buttocks. I was cute, but in ways unlike other boys. Bala was my sister, one year my elder. Soon after I was born, my mother and father sent her to live with my grandparents in my mother’s village, because they needed a child at home. My mother and I visited them for three months of the year. I adored my sister. Those were good times. They didn’t last.

Difference is not appreciated in the severe, unforgiving villages from where I come. I was different from other boys. I knew it. Others sensed it too, and soon enough, my free babyhood pass expired. School began. It wasn’t far from home, and I would return home for lunch and go back to school once done. My mother, out in the fields with my father because there was no one else to attend to at home, would leave food on the table for me.

One day, at the age of eight, an uncle met me at the empty house. He raped me. I got back to school late, limping and bleeding. The teacher sized up the situation immediately. He beat me and berated me in front of the other kids, who laughed at the spectacle. He called me ganduwa, a name, which along with Balbir, stuck. Life changed with those names. In my eighth year I said goodbye to my little rural world and spent the rest of my childhood in hell.

My uncle threatened me for my life, and worse, to tell my father of my wickedness. Once he realized that he was in the clear, I, dirty little secret, became an easy, regular victim for him and many other random associates. I got passed around. Another uncle, khap cronies, and senior boys at school, some who later became police officers, joined in. These were, or became married men with children. All of them. A number still live in the village today. The terror of the threat of my dishonor and humiliation before my family and the people of the village guaranteed my silence. By my teens, rape had become an everyday event in my life. Today my body bears the scars, and chronic health problems, of having been torn up for years.

I methodically hid and disposed of the bloody rags I packed between my legs, but how could they not have known? I excused my mother, but hated my father. He had failed to protect me. I didn’t get to ask him why that was before he died, but as I entered my teens, I began to fight with him while he lived. My father and I fought daily wars over money, over the beatings he meted out to my mother, but much, much more than he ever understood.

Abused children with some inner resources still intact manage to find ways to cope. I found refuge at the edge of the canal that bordered our plot of land. The canal ran east to west, touched the horizon, and gave me sunrises and sunsets. Nature offered me respite from the chaos of the world of people, my enemy. If others were around, I kept my distance. My ears became inured to the taunts. Nature became my friend. However truthful and dependable it is, it didn’t offer me protection from people. I needed to go back home to eat.

I began to unravel. I hit my teens and bunked school, smoked, stole, fought with my fists, broke into houses, and mugged people on the outskirts of the village. I was on course for killing or getting killed. At 15, I ran away from the violence of the village and landed square in the violence of Delhi.

That I’d find in Delhi people more ruthless than the person I myself had become tested the limits of my comprehension. The brutality of the village had battle-hardened me, but I landed in the city, incredibly, an innocent. My first night at the Old Delhi station I was robbed of the few hundred rupees I’d taken from my father before leaving home. Within two hungry days and nights on the pavement, I descended into abject penury and began begging. I lined up at temples for food, joining India’s sickest and saddest people. Within the next few days I started finding odd jobs washing dishes, sweeping floors, and running errands for small-time shopkeepers, one more shrewd and underhanded than the next. I sold coconut, corn, and all kinds of trinkets at car windows at big-road intersections. I fell in with a group of sex workers. They dressed me up and painted my face. I sold my body.

Long-distance truckers picked me up and took me on as a cargo boy. I traveled as far as Bihar and Assam, but once out of Delhi the raping started again. Of the two truckers who were my attackers, one was exceedingly deranged and vicious. One very bad night I realized that to save my life, he would have to die. In our death fight, he came within inches of losing his life at my hands. I pulled back at the last moment and escaped back to Delhi, wrecked.

It was a rare stroke of good luck that I found work as a servant for a well-to-do family in Haryana, where I began, for the first time ever, to put together the pieces of my shattered life. I had access to the books of the house and there I found the novels and short stories of Munshi Premchand, who wrote of the struggles of the exploited. I found myself everywhere in those books, and they planted seeds of consciousness.

If I had had to stagger back into my village a broken young man for everyone to jab at, and to pick up where I’d left off, I never would have returned. Instead, almost a year and a half after leaving, I re-entered that lost, god-forsaken world emboldened, smouldering with rage, and ready to battle to reclaim what was mine — my own life. My former abusers were thrilled to see me, but I taught them quickly that I would expose them for their crimes, even to my own father, and that they would die before touching me again, and never again did they. My mother, I learned, had kept vigil by spinning at a charkha, but without thread, each night of my absence. My father said nothing when I returned, but wept privately.

I finished out my teens back in school, studying what I wanted, defying my father’s orders, which I laughed at. My interest in art began as soon as I could hold a pencil, but in my village, girls drew and sketched. Boys didn’t. I deflected the harassment I got for being the only boy in drawing class in secondary school. I didn’t care.

I entered college at Baraut for art, geography and history, despite continued opposition from my father, who wanted me in the police or army. My programs of study were mostly theoretical, not practical, so I drew on my own. I drew a series of figures based on the cave paintings at Ajanta, which I saw in books. Somehow, my work was discovered back at the village, and word spread that I was making obscene drawings. I was called out and ostracized for depravity by people who knew nothing of art. No one in the village had any knowledge of Ajanta, and trying to explain was pointless. This was the time when my sexuality was emerging, and I knew instinctively that I had to keep that a secret. I panicked and destroyed some drawings, and hid others.

I continued on to Agra for MA studies in art, and lived at the hostel. There I entered into a relationship with another boy. For the first time in my life I had sex that was consensual. I fell in love. He claimed to love me back, but he was game playing. One day he let me know that he had a girlfriend, and that I should get one too. I was crushed. I wanted to be his one and only, to hold onto him, so I did what he said and tried to enter into a side romance with a girl who liked me. I failed utterly. I broke down and confided everything to my hostel roommate, who then outed me. By next morning gossip that Balbir was a homosexual had reached all corners of the campus, and the stares, whispers, and jeers began as soon as I stepped outside. I’d survived my shattered youth, but I couldn’t endure the shunning and humiliation at Agra. A feeling that I’d never fit into this world took root and grew. I’d won many fights in my 22 years, but none of that mattered because the final battle was lost.

I was done. I walked along the railroad tracks outside the city on the longest, last day of my life, and lay down. I don’t know how much time passed. I don’t know if the jolt I experienced was a moment of clarity, or the train itself. But within that instant I understood that I wanted to live. I remember trying to claw myself off the track. Time ran out. It came too fast. Like thunder rolling across the sky, it exploded, faded, and disappeared. It came. And went. And took my legs. I pulled my mangled body alongside the tracks on my elbows several kilometers, until I reached the first village.

When I regained consciousness in hospital, I was stung that I was alive. Crazier than that was the realization that I was still gay -- a fact I understood, finally, I’d never be able to kill. That’s how my awakening began, though coming out to the world didn’t happen until 15 years later. Mike doesn’t believe in rebirth, but says that if anyone was ever born again, I was in 1996. I’ve said it many times before, out loud and in print: I lost my legs, but won my life.

That I would live after the “accident” wasn’t a given, and certainly not a medical expectation. I spent three months in hospital between life and death. When my hemoglobin reached the minimum level for receiving anesthesia, the first of several surgeries began, and I was amputated at the knees. I spent the next year at home in bed. How ashamed I was to be a young man fed, washed, and toileted by his mother and little brother! As an escape I returned to drawing, on scraps of paper, anywhere I could get them.

I don’t know how, but mercifully, the news of my outing at Agra didn’t travel with me on that long road back to my village, but once there, I continued to put up with the long running open secret that I was a ganduwa to simmer on. I was brimming with rage, and dared those who thought themselves more clever than I to ask me questions to my face. They got the verbal equivalent of a kick in the teeth. People withdrew from me, and stared from a distance. Good, because I wanted space from them, too. I cultivated a reputation for ferocity, not unlike when I was a delinquent teen. As for the “accident,” I let it remain just that. Neither my family, nor neighbors said anything of it, at least in front of me.

From my bed I resumed my studies with the help of an exeptionally kind college professor, Chitralekha Singh, who sent me books and exempted me from class attendance. When I was able to get up, and return to Agra to sit for exams, she found a charity that donated me a hand tricycle.

We were broke. Physically and spiritually. My father spent every last rupee on my medical care. Bala died in the third year of my accident. My beloved sister had entered into a bad marriage. Just months after the birth of her second son, her husband and mother-in-law beat her to death when she refused to meet their unending dowry demands. Arun, my little brother by thirteen years, was still too young to earn, so once I left my studies I needed to find work. I was invited by an entrpreneur to help him found a new school in the village and to teach there. I had the hand tricycle, so I could get around. We divided forty students between the two of us. I started out making 700 rupees a month, but that depended on whether or not families paid their fees. The school was a success, and it grew. I worked there for six years.

In the year 2000, the Jaipur Foot Foundation fit me for prosthetics. They were heavy and clunky and they hurt, but I learned to manage with them, and they changed everything for me. For more than a decade I used them for getting to work, in and out of Delhi, and to look and feel more normal. After I met Mike, we began saving for new imported legs, with hydraulic knees. We got them, but they were impossible to use, despite months of trying. We decided to abandon prosthetics altogether, and only then did I begin to feel more able in life and suffer less pain. I now rely on a wheelchair and rubber kneepads I sewed together for when I need to get around to do things the chair can’t.

Despite that I had work, and an income, though meager, life was a daily grind. Drawing became my refuge and saved me from despair. I taught by day and drew at night. I used the cheapest ballpoint pens I could find, and I continued to scavenge paper. There was no money left over for paint, brushes, or canvas, but still, I developed a practice. I picked up cheap used art books and catalogues from the Daryaganj market and dissected every fuzzy black and white image they contained. I began to invent my own subjects and characters, and concoct my own techniques.

In 2003 I entered an M.Phil program at Agra and like before, was exempted from attending class. With the prosthetics I was able to get to Agra by myself to sit for exams. I lived on the platforms of the train station while I was taking them. The first night, I removed my legs from my body and lay down on a bench under a sheet I’d packed with me. Early the next morning I was awoken by screaming people and police officers, who thought they’d discovered a severely dismembered cadaver. Those sorry folks were in for an additional shock when the upper half of that body opened its eyes and sprang up.

That, dear reader, is your breath of comic relief, in what I know is so far an exceedingly bitter story. If I’ve seemed remote during its telling, it’s not for lack of feeling. There are heavy emotional and psychological tracks that accompany this narration, but I hope you will agree that adjectives like scary, confusing, devastating, and even hopeful are superfluous here.

I plowed on. I passed the NET-UGC and interviewed for a lecturer position at Allahabad. On the panel was Dr. Yogender Nath Yogi, then president of the Uttar Pradesh State Lalit Kala Akademi in Lucknow. I was carrying with me some of my drawings, which he asked to see. I didn’t get the job, but he was impressed by my work, and asked me for my artist résumé. He was appalled that I didn’t have one, and that I’d never considered showing my drawings. He put me in touch with Dr. Sabita Nag, who was the head of the art department at a college in Meerut.

Dr. Sabita became my champion. She got my work photographed, helped me fill out applications for group shows at the state akademis, and helped me sell my first drawings. When I speak of my mother, I could be referring to my birth mother or to Dr. Sabita.

I won state and national level awards. Dr. Sabita connected me with a Mumbai corporate group that bought my work. They bought up everything I made, without conditions. I handed over my village school to new leadership and threw myself into my artwork full-time. The 135 drawings and paintings I sold to that company over five years kept my family afloat. I knew I was selling on the cheap, but I was grateful nonetheless for the money. It gave my father delayed medical care, and my brother an education, and eventually, a government job and a big wedding.

Emboldened at winning awards and selling work, I ended my relationship with the corporate group, left my village and moved to South Delhi, fully ready to join the arts scene to exhibit, market my work, and be part of a community. Ha, ha. The gallerists unmasked me for who I was: talented, but naïve -- an ultimately Hindi-only speaking village artist out of his league, trying to fit in to a world of upper-class Delhi manners and English accents. I was a foreigner in my own country. After three fruitless years trying to fit in, and failing to exhibit or sell paintings, I was broke and needed out. Determined to show that I’d done something before slogging back to the village, I applied for and landed a solo show at Triveni Kala Sangam.

This was the turning point. The Bonding of Spirituality was a success beyond all my hopes. I sold half of the paintings I put up. Still, it wasn’t enough to sustain my artificial stay in South Delhi, though it made me believe that I’d get back there for real, someday. Knowing that I was living on borrowed time, I’d been applying for government lecturer jobs and got one as a school teacher of art thirty kilometers from home. With that I was able to quash any shame of returning to the village empty-handed.

I know that this article is meant to be about my coming out as a gay man, and I hope, patient reader, that I’ve conveyed, over these last few pages, that I’m addressing that, while perhaps taking a scenic route in getting there. It was never a straight point A to point B line with me. No one should have the idea that I came out when I was outed at Agra. No, no. The college was nearly 300 kilometers from my village, and I slammed shut the closet door on the way out. Mercifully, there were no smart phones or social media in 1996, and my accident didn’t get into the press.

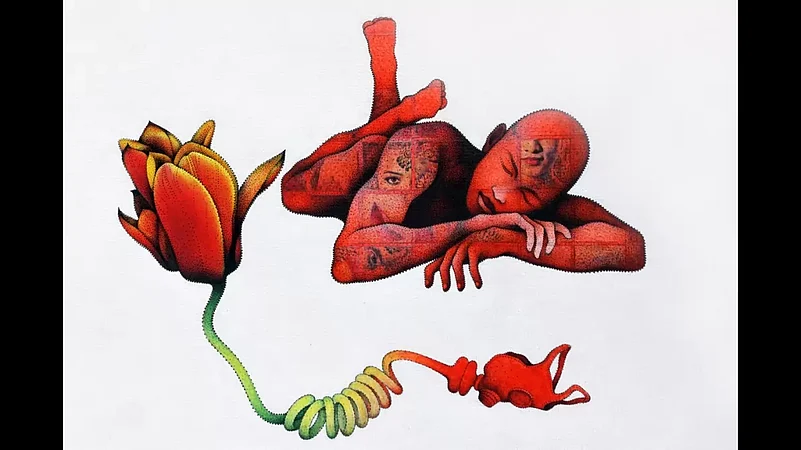

My real coming out unfolded through the long arc of my artwork. If my biography was raw, so was my early work, because reflected in it was my life. After the accident, I painted wretched children and suffering humanity because I was that child against that backdrop. And then, what emerged from the violence and injury in those works is transformation. This was during the mid-aughts. My subjects grew quieter and more introspective, were in dialogue with themselves, having conversations on success, failure, pleasure, pain, and dreams. All of these figures are men, and clearly they are my own incarnations, as I journeyed into my past, back to my present, and ahead to my future. These men are moving on to something better, though they may need to pass through purgatory before they get there. Some may turn to ash before they rise again.

Like thirst and hunger, I ached to draw and paint the male figure for as long as I can remember, and I wanted to paint men in all their naked beauty, in the same spirit that women had been celebrated in their own nudity throughout the history of art. My reserve was based on what India, and gallerists in particular, were prepared to put up with. I took my first full-frontal painting to get photographed at the busy studio in Meerut I’d gone to many times before. I took out the painting. The eyes, whispers, and several direct admonitions made me retreat. When I got home I scrubbed the penis, already cloaked in abstraction, out of the work completely.

Though I was pleased with the direction my art was taking, troubling thoughts and feelings were stirring in my personal life. I was restless. I’d been carrying on an unsatisfying relationship with a young, straight man who tried to be gay with me, which I knew from the start would not end well. The men in my artwork began to behave differently. I began painting nonstop. I didn’t direct the artwork as much as it directed me.

I opened my second solo exhibition, Out Here and Now, at Delhi’s Lalit Kala Akademi at the end of 2011. On exhibit were paintings of men who were nude, together, fully sexual, if still detached emotionally. I painted my subjects over hundreds of tiny sexually-charged images that I’d amassed from the internet and printed on canvas. Art historian Johny ML wrote up the catalogue. It was he who challenged me to come out as a gay man publicly in print, and I accepted. I came out in that catalogue and at that show.

Many artists and other visitors who came to the show praised my work, and that invigorated me. Still, Lalit Kala Akademi, a government-sponsored cultural center, has eight galleries in its arts complex, so some people wandered into the show without knowing what they were getting into. I was up against some very negative reaction. Even a number of established artists I was in regular contact with cut me off when they saw my male-centric work and learned that I was gay.

The second day of the show I fully understood how risky it was to have staged it. I began receiving anonymous phone calls accusing me of polluting Indian culture, warning me to close the exhibition, and threatening my death. My posters around town were getting torn and defaced. I was unnerved.

Two days later, a masked intruder stole into the gallery and attacked me while I was filming a gallery walk. He smashed a painting before fleeing. Immediately after, my family pressured me to cancel what remained of the exhibition and return home. While I was between hospital and the police station, a friend began to pack it up for me. That’s when several artist activists -- Johny ML, and photographers Ram Rahman and Sunil Gupta, converged at the gallery to insist that I keep it open. They arranged round-the-clock protection for me. They broke news to the media, which picked up the story and reported it as an act of extremism and an assault on free expression. The resulting publicity embarrassed the police into taking a report, which they’d initially refused to do, having accused me of asking for trouble and deserving what I got.

Johnny, Ram and Sunil worked their contacts, and the LGBT community of Delhi rallied and showed up at the gallery en masse. It was the first time ever that I’d met people who identified as out, gay and proud, and it was a revelation. Camaraderie like that was entirely new for me. At my core I was still a Jaat villager. I’d had no experience with the urban gay rights or social scenes. These people changed my concept of identity, and how I wanted to live.

Before the show’s closing, I had an additional, especially auspicious meeting at the gallery. A supportive artist wanted to introduce me to a gallerist who’d recently returned to Delhi after several years in New York. Myna Mukherjee was an activist in feminist, queer, and social justice circles, and had been building an arts center in the South Delhi enclave of Shahpur Jat, which she called “Engendered.” We met, and astonishingly, she took me on as an exhibiting artist. With gratitude, our relationship continues to this day.

Life didn’t exactly follow an upward trajectory after coming out to Delhi’s art world. There was more work to be done. Mike had been living in Delhi since 2007, but we first met in 2012 when he showed up to see work that I was exhibiting at Pragati Maidan. I was still living in the village and working at my school when at the end of 2013 the local Hindi press reported, out of the blue, that I was getting married, to a man. Madness ensued. My family revolted. I lost my job. A confidante warned me that the village khap was moving against me.

Mike begged me to come home to Delhi, to stay. I did, but not before relatives from across the family hinterland swooped down on me at home in the village to stage an intervention to force me to publicly denounce the reported news and then marry a woman that they would provide. I battled back and called out two in the room who had abused me in my youth. They called me a liar, but the assemblage was shaken. That kind of confession, by a man, is never supposed to come out. But come out I did, and this time without caring a whit about any consequences. With my cane I steadied myself on legs, left the village, and never returned.

Neither was I going to worry about official reaction to my work, which had been growing increasingly censorious as attacks on freedom of expression were ramping up across the country. Though it was supposed to have achieved the opposite, with the 2012 attack I was done with self-censoring, even doubting my art, and though I knew I was at greater risk, I was seeking greater truth in my work and integrity as a man. Several times over the next few years I had exhibitions shut down, censored, or threatened with confiscation by the self-appointed moral police, as well as the government.

By 2016, Mike wanted to leave his job and return to the US. I suppose the time was right for both of us. We settled in New York City. From afar we watched with concern the darkening atmosphere over India, but then, in 2018, the end of Section 377 was settled by the Court, and our faith in justice rebounded. No longer were we criminals in our own country. How we would treasure a return to India with as married men, legally recognised. All of us, no matter who we love, should be able to participate equally in the rights, responsibilities, and benefits of our India. Here’s looking at you, again, Supreme Court.

I suppose the ultimate coming out would be taking Mike to the village as my husband. My family knows him, and though my mother won’t say his name when we’re on the phone, my niece and nephews do, though they most often refer to him as tauji or mamaji. But I’ve come out so many times, in so many ways over the last ten years — about my sexuality, my youth, my “accident,” my art, my marriage to Mike, relocating to the US, that coming out has become a mantra, the truth about who am I, what I do, and everything I want to do and be. I am Balbir – a real artist – out, gay, proud and happy, nearly 50 years of catastrophes and triumphs after my start, stepping out, journeying out, still coming out, into the world, and lusting for life.