After the initial sense of grand tragedy ebbed, the image of lakhs of migrant workers returning to the village brought about a nostalgic turn in the minds of some urban commentators. They were once again seduced by the notion that the Indian village is an enduring space from an ideal past—the last refuge of sanity, order and values in times of global disarray. A resilient idyll. Some were moved to recall the gram swaraj alternative as envisaged by Gandhi. Some felt it was a reading of values that had exerted its pull on migrant workers: they had seen through the cities as a morally doomed hell, and their love for the villages seemed infinite on the rebound. The city appeared heartless, the village compassionate. But all that vicarious love sprang in urban hearts without conceding the fact that the Indian village is itself the problem. It is the first of the maladies for migrants, the very reason why they are migrants.

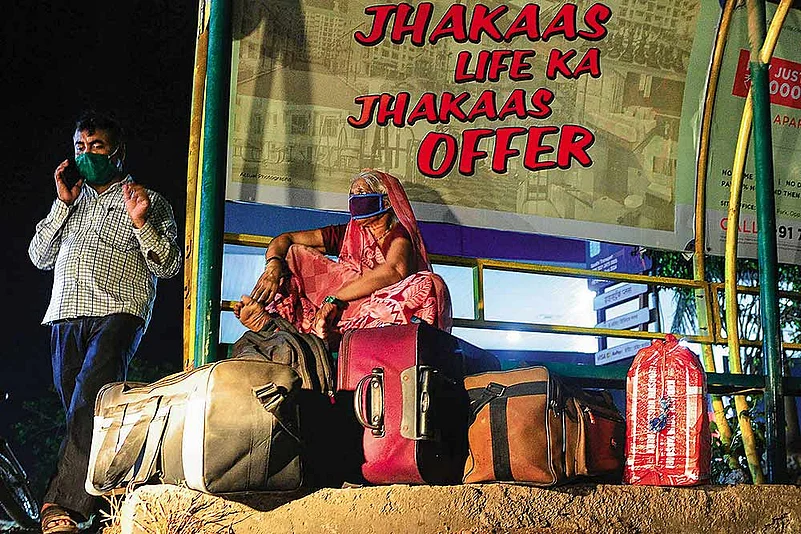

The problem of migrant workers is not to be defined in terms of a choice between village and city. It is about a condition in which they are neither part of the village, nor part of the city. Privileged migrants can belong anywhere. They can feel equally at home in Sydney, Dubai and Toronto..and move seamlessly between Gurgaon’s Cyber Hub and Koramangala’s pubs. They are in ‘hometowns’ when they come to Patna, Patiala and Palakkad. Villages are their ancestral lands. But the migrant labourers are literally called pardesi/bidesi at home and pardesi outside. ‘Those who have gone to other lands’, and ‘those who have come from other lands’. Outsiders in the village. Outsiders in the city.

The usual way of seeing the relationship between migrant workers and the village is the economic one. But this entails only one part of the problem. Migration is a response to a deeply socio-cultural malady too. The Indian village creates a horrendous condition for people; it impels them to migrate. It makes the lives of women, Dalits and other disempowered castes an unspeakable hell. It is a graveyard of individual freedom and equality, the deathbed of justice and dignity. It cannot see Dalits wearing a new dress, or slippers, or riding a horse. It cannot take women walking about freely, or ‘laughing-out-loud’. Ideas and people cannot meet or mix, new winds cannot blow. It is adverse to love, life and freedom of mind. Hierarchies are so entrenched in village life that any possibility of equality becomes impossible.

Thinking about the village is also about which side of the village you are on: east or west, north or south or in the corner house? Which side of the village is the temple, which side is the garbage dump? The location of your house is also your social location in the village. Social control is routine and supreme; constraints are the norm, and everything is marked to that end. Castes are marked, communities are marked, houses and streets are marked. Objects and places are marked—hence, also, mobility. The village is already a quarantine zone. On the social map of the nation, it has to be marked in the red. As Ambedkar said, “It (the Hindu village) is a case of territorial segregation and of a cordon sanitaire.”

The love of the Indian intellectual for ‘the village’ is nothing but love for the genealogy of their feudal-savarna caste lineage. Unless you are a feudal, you cannot feel proud of the village or its litchi gardens. Can the landless labourer, who slips in the darkness and silence, feel proud? What stories will you tell when you don’t have those rolling acres, those ponds and mango orchards? The pride comes from a sense of possession. Production? No, that’s something else. That’s what division of labour is there for. The lion’s pride, pardon the pun, comes from its power to prey upon other life. For the migrant worker, the city may be cruel and indifferent, but the village is a life sentence that you escape. A life sentence is not a life, and fugitives cannot be nostalgic.

Yet, there is still the soil and the language. Yes, I love my village. But if you’d ask me to live there, I wouldn’t unless I’m left with no choices. I don’t like the city. But if you’d ask me to leave it, I wouldn’t unless I’m forced to. This is not a Chinese proverb that the nation can uninstall like an app. It’s about the central paradox of life in which a nation of precariat lives. I’m not a migrant labourer who can represent the ‘I’ of them. But I could have been one of them. Once you have been in the village, it lives in your lives—in your dreams and subconscious, in your sleep and anxieties. It’s part of your body, rhythm, language and map. It follows you like a shadow. It haunts you like a ghost. It lives in your brutal memory and also in a sense of belonging. It rings in your violence, your silence and feelings. When you are sad, you cry for it. When you are happy, you sing for it—a land of social distancing but cultural belonging. Like being together apart. Like a separated lover, it dwells in your eyes and longs in your heart. But like a jilted lover, it drains your emotions and breaks your confidence when you meet.

One who migrates never regrets. The regret is that someone is left behind. They are the one who sing the songs of separation, or the migrants sing in their image. They would be happy to leave the village, to not to have to sing that painful song again. But do they have space in the cities?

Migration is death

In many north Indian languages, the metaphor of death and migration is the same. So are their songs and imageries. Both draw their energies from each other; they merge and become mirages of each other. Take the famous Bhojpuri song, Chadhte fagun jiara jari gaile re: “The arrival of fagun/burnt my heart/How did my beloved/forget my love?/He went abroad, and didn’t return/Neither does he send a message/Does that country not have a cuckoo?/Did the papiha die here?” Songs like Kaune khotwa mein (in which nest do you hide, my beloved bird), kaune nagariya mora saiyanji ke dera (In which city has my beloved put his tent) and others echo this prototype. Is it about death or migration? It’s about both. Both the migrant and the dead take that arduous journey to pardes…the unseen, alien land. Take it as fate or fact. For that society, migration is destined like death itself. It’s not a pilgrimage one takes to understand the deep meaning of life, but a journey to make a bare minimal life. Or a death.

For, the journey itself is about violent separation from the loved one. Also, dissociation from caste and community chains. To lose identifications entails the loss of family and familial identity. Perhaps that’s why migration is equated with death. If life is the name of belonging, death is its severing. What do feudal families do when a girl elopes with someone outside the caste? They declare her dead in the first performative act. They often perform her death ritual to mark this dissociation; she becomes the living dead. Any attempt on her life is seen as a pious act, so the ritual is only a prophecy of the real. But the very dissociation marks the potential of love and freedom. For those who risk their life for love, for the one who leaves home for dignity, it inaugurates a new life. Death is an opening. One has to die to get a new life, to mark a new subjectivity. One migrates to escape the everyday deaths.

But some also return to migrate again—strung in between caste dynamics at the village and the nature of their job in the city. While outside, they all carry strong elements of bidesia bhav, alienation. But as soon as they re-enter the quarantine zones of the village, jati bhav takes over. This does not mean the village is unchanging. It’s disintegrating, sometimes for the good, sometimes for worse. One hoped the cities would be different, a space for freedom. But what happens when the city mirrors the villages? This is the starkest of ironies. Go to Ambedkar’s words: ‘What is the village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism?’ That fits the city today! Look at Delhi, the Jat galis, Jatav galis, the elite RWAs blocking some communities…. The Pinjra Tod women, in their very name, ask for what cities are supposed to offer: freedom. And they are locked up! And yet, it is the city that still offers hope in its anonymous openness. The migrant workers will migrate again.

Dr Prakash is an Assistant Professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU (Views expressed are personal)