In the intricate tapestry of Jammu and Kashmir’s sociopolitical landscape, where history and aspiration intertwine, a profound shift is quietly taking place. The recent overhaul of reservation policies in Jammu and Kashmir is poised to redefine the landscape of opportunities for the region’s youth. As the government expands reservation quotas for various communities, the aspirations of merit-based candidates are increasingly being overshadowed and their future prospects have been narrowed in ways that are both immediate and long-lasting.

This article delves into the far-reaching consequences of the recent reservation amendments―which have significantly broadened the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) list by incorporating 15 additional castes and instituted a notable 10 per cent reservation for the Pahari community and other tribes under the Scheduled Tribes (STs) category―reflecting the voices of all stakeholders. However, the overarching concern persists: do these new reservation rules violate the 50 per cent constitutional cap? Many news reports suggest it does. Drawing from the recent legal precedents, such as the Patna High Court’s ruling against Bihar’s attempt to exceed the constitutional reservation cap, this analysis explores the potential constitutional challenges these new policies could face.

While the Supreme Court on August 1 affirmed that states are constitutionally empowered to create sub-classifications within the SC and the ST categories, they must demonstrate that the sub-classified groups are indeed more marginalised. The need to uplift historically marginalised communities is undeniable, but it must be done in a manner that does not undermine the aspirations of those who strive on the basis of merit.

As Jammu and Kashmir stands at this critical juncture, the need for a balanced approach has never been more urgent. This is not merely about policy—it’s about the very future of a generation, whose dreams of advancement may be eclipsed by the shadow of these new rules. The delicate balance between social justice and merit hangs in the balance, and how this is navigated will define the region’s socio-economic fabric for years to come.

The government’s decision to expand the list of OBCs by adding 15 new castes and increasing the reservation quota to eight per cent marks a significant shift in the region’s socio-political landscape. Additionally, the inclusion of the Pahari community and other tribes in the ST category, with an added 10 per cent reservation, has further tipped the scales.

However, these changes have been introduced without a corresponding increase in the number of seats available in educational institutions and government jobs. This lack of expansion in opportunities has resulted in a significant reduction in seats and job opportunities available for general category candidates. They now find themselves competing for a rapidly shrinking share. The general category―which previously had access to around 45 to 50 per cent of seats and jobs―has now been drastically reduced, leading to heightened competition and increased pressure on the youth of the region where now a large population group will compete for a less number of seats.

Kashab Sharma, an assistant professor of history in the Higher Education Department of Jammu and Kashmir and a member of the Pahari community, offers a critical perspective. “While the allocation of an additional 10 per cent reservation to the Pahari community could advance their development, it also raises important questions about the fairness towards open merit candidates. Although the Pahari community faces unique challenges that may justify their ST status, the additional quota diminishes the opportunities for others. This situation underscores the delicate balance required in reservation policies—to uplift marginalised groups without compromising equitable access for all. A thorough review of the socioeconomic conditions of both Pahari and open merit candidates, coupled with an exploration of alternative solutions, could lead to a more balanced policy that supports the Pahari community without unfairly disadvantaging the others,” he says.

Drawing parallels with other states such as Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, where similar expansion in reservation quotas have taken place, it becomes evident that the impact on general category candidates has been consistent—fewer opportunities and greater competition. The recent Patna High Court judgement, which struck down Bihar’s decision to reserve 65 per cent of government jobs and educational seats for various castes, underscores the delicate balance that must be maintained between social justice and meritocracy. The Supreme Court’s refusal to stay the Patna High Court’s order further highlights the judicial concern over breaching the 50 per cent reservation cap.

In the context of Jammu and Kashmir, these concerns are particularly acute. The current reservation quota, excluding the Economically Weaker Section (EWS), stands at 53 per cent, leaving the open merit category with just 37 per cent of the opportunities. In a region where the unemployment rate is already one of the highest in the country, this reduction in opportunities is likely to exacerbate the struggles of the youth.

Voices of the Youth from J&K

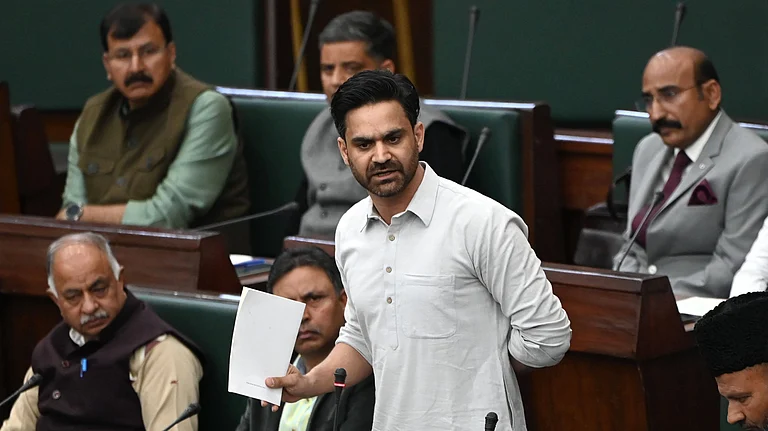

While discussing the impact of the new reservation policy in Jammu and Kashmir, it is critical to include the voices of those actively involved in the movement against these changes and those who favour it. Vinkal Sharma is spearheading the youth movement against the recent reservation policy changes deeming it as a murder of open merit. “The Jammu and Kashmir administration’s decision to increase the ST reservation by 10 per cent at the expense of open merit is a blatant disregard for meritocracy and fair opportunities,” says Sharma. He highlights that while the Gujjar-Bakarwal communities have already moved the High Court challenging this decision, open merit candidates have launched a pan-J&K movement to fight against the new policy, both politically and legally.

Sharma also points out the significant challenges faced by the youth in Jammu and Kashmir, where there is a lack of IT parks or a robust private sector, leaving government jobs as the primary source of employment. “Open merit candidates survive on merit, and for the last five years, changes in reservation policies have disproportionately affected them,” he says, referencing the impact of past policy changes that reserved certain government jobs exclusively for undergraduates and disadvantaging graduates.

Drawing attention to the specifics of the new rules, Sharma explains: “In the recent recruitment processes, of the 1,200 posts for sub-inspectors, only 293 were allocated to the general category, when the allocation for open merit candidates was 50 per cent. Now, with the reduction to 40 per cent, the impact is even more severe. Just to gain a few seats in the assembly, they have sabotaged the careers of thousands of open merit candidates.”

Furthermore, Sharma draws parallels with the Patna High Court’s ruling, which struck down Bihar’s attempt to increase reservations beyond the 50 per cent cap, as a potential basis for challenging the current policies, emphasising the importance of adhering to constitutional limits. The Patna High Court invalidated the reservation policy on the grounds that it exceeded the constitutional limit. While the Bihar government conducted a caste census revealing that the lower caste groups formed a majority, leading to a 65 per cent reservation allocation, the court ruled that such a quota breached the 50 per cent cap established by the Constitution, and therefore, could not be upheld.

A civil service aspirant from the remote Poonch region, who was recently granted the ST status, says that while reservation for the Pahari community is justified, it is crucial to conduct a caste census to determine their true representation alongside other communities like the Gujjars and Bakarwals in Jammu and Kashmir. He emphasised the significant disparity in opportunities and basic facilities between the Pahari regions and more developed areas like Jammu and Srinagar. Unlike those who migrate for better education by choice, Pahari students are compelled to leave their homes simply to access basic education, which places a heavy financial and emotional burden on their families. As underdeveloped regions lack even basic healthcare and educational facilities, the aspirant argued that the right to equal opportunities remains elusive, violating the spirit of the constitution. He stressed that a caste census is essential to ensure that providing justice to one community does not result in injustice to others.

Navigating the 50 per cent Cap on Reservations

The Supreme Court, in its landmark judgement in the Indra Sawhney case, capped reservations at 50 per cent. This ruling was designed to ensure that merit-based selection would not be unduly compromised. However, the new policies in Jammu and Kashmir, which push the limits of this cap, raise significant constitutional questions.

The potential breach of this threshold invites legal challenges and poses a substantial risk of further complicating an already intricate situation.

The youth of Jammu and Kashmir are no strangers to challenges. The region’s tumultuous history has often placed them at the crossroads of conflict and opportunity. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the unemployment rate in Jammu and Kashmir hovers over 21 per cent, significantly higher than the national average.

This bleak employment landscape is further darkened by a series of high-profile recruitment scams that have rocked the region in recent years. From the J&K Bank recruitment scam to irregularities in the selection process for government jobs, these incidents have eroded the trust of the youth in the system. Many candidates, having aged out of eligibility due to prolonged delays and scams, now find themselves with little hope.

The new reservation policy, though intended to uplift the historically-disadvantaged communities, risks unraveling the delicate balance between social justice and meritocracy—a cornerstone of our constitutional ethos. As we navigate this complex landscape, it is imperative that policies are crafted with a nuanced understanding of the region’s unique challenges. The path forward must be one that not only acknowledges the need for equitable opportunities, but also safeguards the aspirations of a generation poised at the crossroads. The future of Jammu and Kashmir hinges on how we reconcile the demands of social equity ensuring that no group’s dreams are eclipsed in the process.

(The author is a policy analyst from Jammu and Kashmir)