On June 24, 2025, the Election Commission of India (ECI) issued a circular asking people in Bihar to submit documents proving citizenship (such as birth certificates, passports, etc) as part of a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls. This was especially focused on those whose names were not on the rolls before January 1, 2003, implying that they had to establish their citizenship in order to vote.

In early July, the Chief Electoral officer (CEO) of Bihar published a newspaper ad that many said softened the rules. It said if documents were unavailable, people could still submit the new enrollment forms to their Booth Level Officer (BLO). It also said the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) would later verify documents via local inquiry.

This has caused massive confusion and outrage: some people thought documents were no longer mandatory, while others were even more confused. Thereafter, the ECI clarified that the original document requirement still stands and that the ad was being misinterpreted. Forms could still be submitted without documents, but a claims and objections phase (up to July 25) would require documentation. The EROs could inquire into missing documents in specific cases.

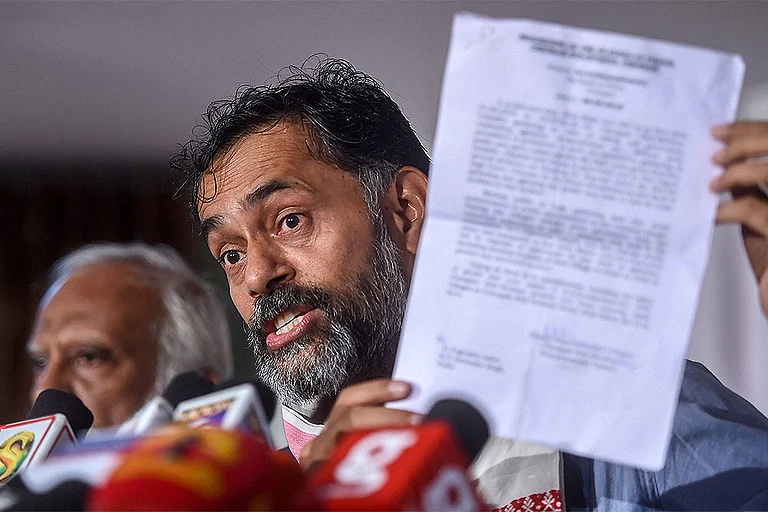

In this interview, Prof Jagdeep S Chhokar, founder-member of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), sounds the alarm over the ECI’s move to revise the electoral rolls in Bihar—a process it promises to make nationwide—based on demanding proof of citizenship.

With ADR filing a petition in the Supreme Court, which comes up for hearing on 10 July, Professor Chhokar warns of potential mass disenfranchisement, especially of the poor, migrants and marginalised groups.

He critiques the opaque process, the shift of responsibility onto citizens and the risk of voter anger on the eve of elections. This, he says, may be a trial run for a nationwide rollback of voting rights. Excerpts from a telephone interview with Outlook Magazine’s Pragya Singh:

Outlook: There’s been confusion about whether the government is still backing the recent electoral developments in Bihar. It seems the process is on hold. Could you clarify?

First, it’s not the government—it’s the Election Commission. That’s an important distinction. Second, the Election Commission, as of now, hasn’t changed its stance on reviewing the voters’ documents. The confusion began with an advertisement published in Bihar newspapers by the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) of Bihar on 24 July 2025. The Election Commission of India (ECI) clarified this in a press note the next day. But it caused a lot of misunderstanding.

In what way?

Some people interpreted it to mean the Election Commission had stepped back and that people had won. That’s false. It’s propaganda. I’ve clarified this in at least 10 to 15 interviews in the last few days—TV, YouTube, newspapers—the documents still need to be provided, as the June 24 communication indicated.

People need to read the third paragraph of the press note issued by the Election Commission of India. It clearly says you have to submit the necessary documents. They’ve only extended the deadline a bit—till 25th August—but that’s just a month’s extension, and woefully inadequate for such a massive exercise. You can file complaints or objections during that period, but the documents are still required.

And most people don’t have those documents?

Exactly. Let me give you an analogy. You’re from North India, right? Often, when you as a shopkeeper how much money he is owed, he responds, “Paisey aa jayengey—don’t worry about the money.” That’s how this is being handled. There’s a vague promise—but without papers, it won’t work, just like you cannot buy anything at a shop unless you pay money.

So the Bihar Chief Electoral Officer’s newspaper advertisement on July 6, 2025, which was soon followed by the ECI’s press note, was misleading?

Yes. It seems like a red herring—possibly with or without the blessings of the ECI. The ad even said that if you don’t have papers, decisions will be made based on whatever documents are available.

And who makes that decision whether those documents are adequate?

The Electoral Registration Officer (ERO). But the ECI has also said: until the draft electoral roll is released, no one can say whose name is on or off the list.

So what do you think is the motive behind collecting forms filled by people—the pre-printed enumeration form, which appears to be a key component of the ECI’s Special Intensive Review (SIR) of the electoral rolls in Bihar?

It looks like the focus is on collecting these forms, regardless of whether people have provided the requisite documents and photos or not. People will add their Aadhaar numbers, mobile numbers (the documents they are more likely to possess) and submit these forms to the Block Level Officers (BLO). Then, visualise the next steps: a press note will be issued to say that “7.9 crore forms have been collected”, matching the total number of voters in Bihar. They’ll claim success based on this. [Reports say, less than 50 per cent of these forms have been collected by July 8.]

But the real test is not the submission of this form but the draft electoral roll, which will be issued, presumably in August, a process managed at the state level by the CEO, Bihar, the District Election Officers, and the EROs?

Yes. That’s when we’ll know how many names made it to the electoral roll. Now, if you have been a voter in Bihar, and find that your name is missing from this electoral roll, you’ll have to go to the Election Commission—with papers to prove your citizenship.

Will migrant workers be able to do that? Will those who don’t have documents be able to procure them even in the one month additional time period?

That’s the key issue. They will not. First of all, people working in Mumbai, Kolkata, Madras, Hyderabad, Punjab, Haryana—will they be able to check the electoral roll in Bihar? No. It used to be the Election Commission’s responsibility to ensure people were registered. Now the burden has shifted to the citizen. It’s like saying: “If you want your name on the roll, come and request us for it.” And who will decide if you get it? The ERO!

What about those who weren’t on an electoral roll before January 1, 2003?

That’s another problem. The ECI’s 24th June circular says there’s a presumption of citizenship for those on the electoral roll as of Jan 1, 2003. There’s a flip side to this statement. It is that for those who weren’t on the electoral roll by that date—there is no presumption of citizenship for them.

That’s a serious issue.

Absolutely. There are two consequences here: First, that names from January 1, 2003 might be deleted without following due process—which is illegal. There is a legal process involved in striking off names from the electoral rolls, but that has not been followed under this new SIR. That’s simply against the law and right to vote. That’s the basis of our petition in the Supreme Court. If there’s no presumption of citizenship, then what are those people? What happens to them?

That could have far-reaching implications.

Yes. If someone isn’t presumed a citizen by a constitutional authority, it’s a big deal. It opens the door to disenfranchisement—arbitrary, discretionary and potentially dangerous.

But hasn’t the Supreme Court said the ECI can’t verify citizenship?

Yes. It has, in 1995 and 2024, and even Mr. Ashok Lavasa, a former Election Commissioner of India (2018-20) recently wrote in The Tribune about how the ECI’s job is to register voters, not to verify citizenship. Citizenship is a given if one’s name is on the electoral roll—the eligibility to vote is what the ECI should focus on.

Is there a correct way of doing this exercise?

Yes, it is that you keep verifying the existing rolls—check if people are still living at the same address, if they’ve moved, died, etc. But this current process is turning it into NRC 2.0—a citizenship check.

What are the larger consequences?

If they proceed this way, it could be disastrous. Imagine a village where 500 people usually vote. Suppose that on voting day, 200 people find their names missing. That’s a volatile situation. If this happens in one or two villages, it may be suppressed. But what if it happens in 100 villages?

That could lead to unrest.

Exactly. Democracy and voting are very sensitive issues. If people feel excluded, especially those who’ve voted for decades, the fallout could be severe.

So, again, is there a correct way to handle this?

Yes. Like I said, the ECI should keep verifying voter rolls continuously, election or no election. Don’t turn it into a citizenship verification exercise. No electoral roll will be 100% accurate, especially in a country as large and diverse as India and with its unique attributes. Mistakes in the electoral rolls should be corrected—not weaponised.

What about migrants? Are they facing a new risk of being excluded in a different way during this electoral roll revision process?

Yes, and I have worked with migrants for 20 years. I was the founding chair of the Board of Trustees of Aajeevika Bureau in Udaipur. While the government has talked about Non Resident Indians (NRIs), getting the right to vote, why are we not worried about MRIs: Migrant Resident Indians? The migrant workers are basically ignored, unlike the NRIs, because they aren’t an organised vote bank. And yes, this process could effectively erase them and the Muslims, Dalits, the poor, and the illiterate from voter rolls. That’s the real danger.

So, if there had not been this kind of one month or two-month deadline to the process, then this problem could have automatically been avoided?

Yes, with more time and, more crucially, proper consultation with everyone involved, this situation could have been avoided. This rushed, forceful process is worrying. Recall that they tried to link Aadhaar and voter IDs earlier. The Supreme Court blocked it, yet they collected lakhs of forms. Now it’s the same story. Forms will be collected, and thereafter, thousands will be found, lying unattended, scattered all over the country. It will be for nothing.

So what happens now?

We’ve filed a petition in the Supreme Court—others have followed, including political parties. But political parties are too timid or compromised to raise this issue adequately. Nobody wants to challenge the system. Everyone’s files are with the Enforcement Directorate. No one wants to be arrested.

Is this a test case for citizenship and voting to be linked inextricably across the country?

Yes. Bihar is the trial balloon. If it succeeds here without resistance, they’ll expand it to other places. Then, 30–50 per cent of the country could end up being disenfranchised. You’ll have citizens without the right to vote, like Palestinians in Israel—I don’t think I need to elaborate further on this