Too Many People, Too Little Training

- By 2020, UP, Bihar, MP will account for 40% increase in working population, but only 10% of increase in income.

- Labour force growth largest in rural areas; employment growth elsewhere.

- Skill shortages a big risk for India. Most future job opportunities in sectors where Indians have little expertise.

- 89% of working population has no vocational training

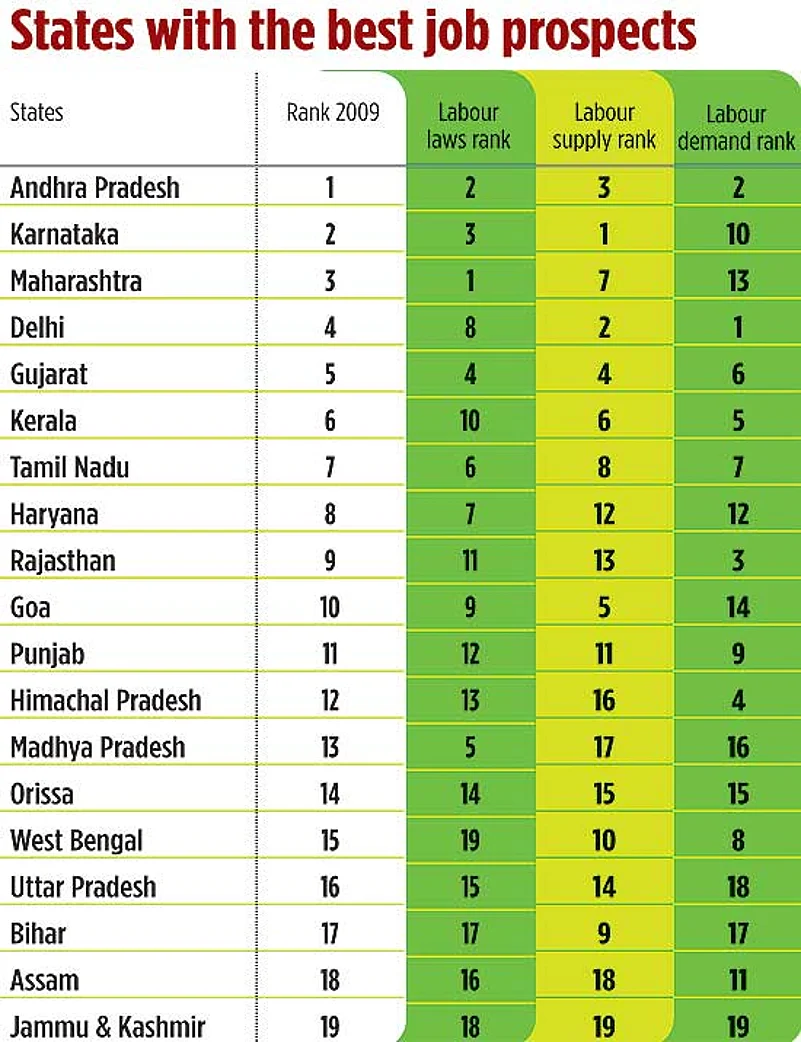

- AP, Karnataka, Maharashtra top labour prospects ranking; West Bengal, UP and Bihar near the bottom.

***

Over the next twenty years, expect a big shift in the political battleground, from the minds and hearts of people to their places of work. Just finding jobs, any job—a task the ‘employment exchanges’ have managed to do for less than 0.5 per cent of registered job-seekers—will not do the trick. Between 2001-06, the country’s population grew from 1 billion to about 1.4 billion, and 308 million of these were of working age or between 15-59 years old. Not only will this number jump even more dramatically by 2025, other serious issues could plague the workforce. Starting with an element of chance that dictates what happens to every person who turns 15 and expects to find employment soon. Not only could the child find he was born in the wrong family, he may do worse—find that he belongs to the wrong Indian state.

“Many of us intuitively recognise that the most important decision a child in India can make is to choose their parents wisely. But the second most important decision the child can make is to choose where they are born,” says Manish Sabharwal, chairman, Team Lease. The Team Lease-iijt ‘India Labour Report 2009’—a survey on the ‘geographic mismatch and ranking of Indian states by their labour ecosystem’—will be released shortly. The report highlights regional disparities in employment, skills development and incomes as one of the most striking labour trends in India. It shows how states need to fight harder to create jobs, as well as create the right working conditions, raise the level of access to education as well as foster new methods of skill development.

Hi-Tech City in Hyderabad

Sabharwal describes as a “tragedy” the mismatch between the much-touted “demographic dividend” and the actual jobs for trained workers. It is only compounded by the fact that jobs are being created in states other than those where most people live. Each of these puts paid to India’s dreams of a demographic dividend. We may be an increasingly youthful nation, but we also have a rising force of unemployed, under-employed, untrained, or incorrectly trained workers. Though people are clearly moving from farm to non-farm jobs, or rural to urban, unorganised to organised, and subsistence self-employment to wage employment, the question is, are they moving fast enough and are states trying to keep up with the changing population profile?

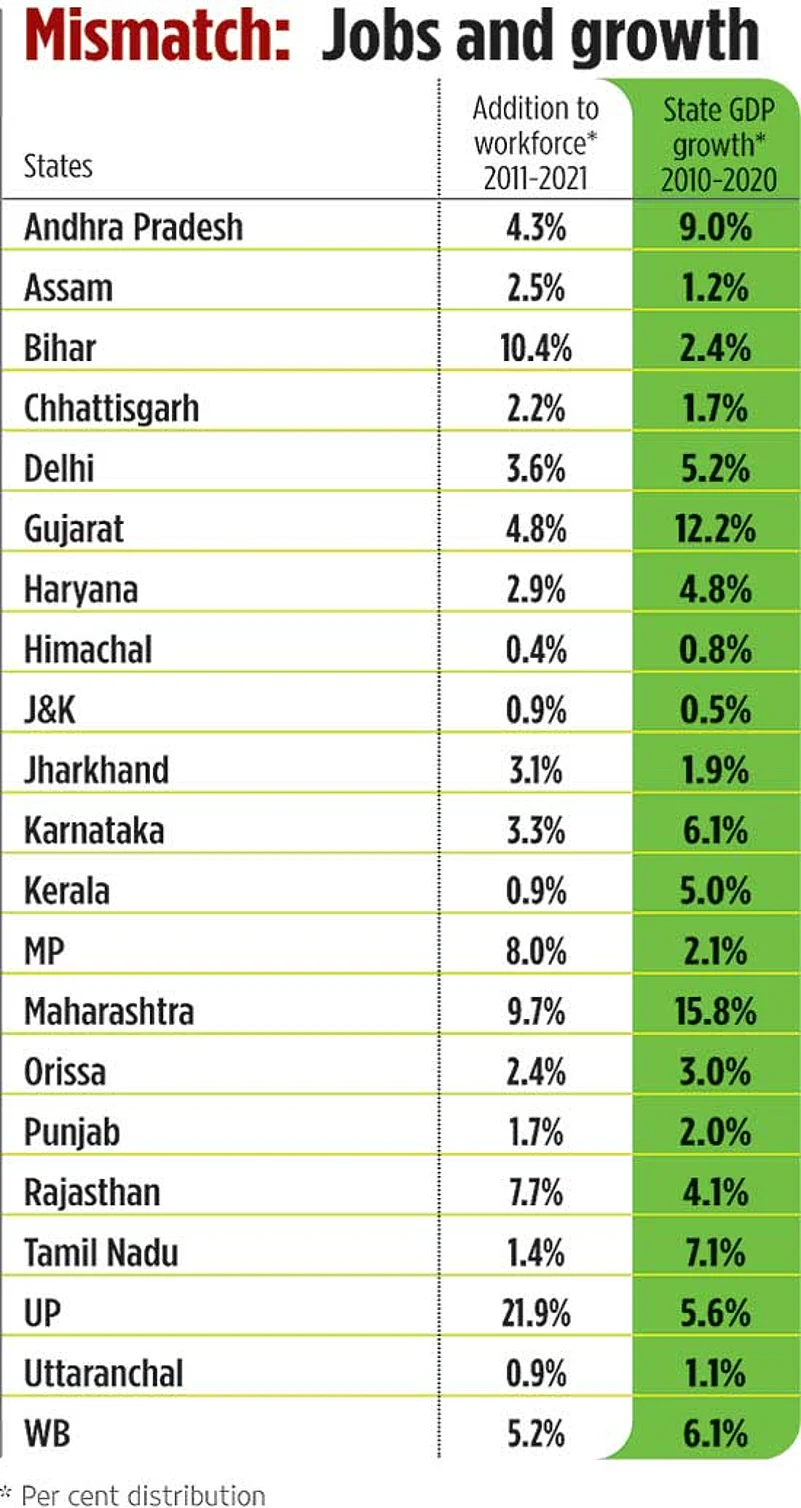

Maybe not. For instance, the report highlights how over the next decade, much of India’s demographic dividend will occur in states with backward labour market ecosystems. This implies that between now and 2020, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh will account for 40 per cent of the increase in 15- to 59-year-olds, but only 10 per cent of the countrywide increase in income. Over the same period, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh will take a lion’s share of India’s GDP growth—up to 45 per cent—but they will absorb less than 20 per cent of additional workers joining the market over the same period.

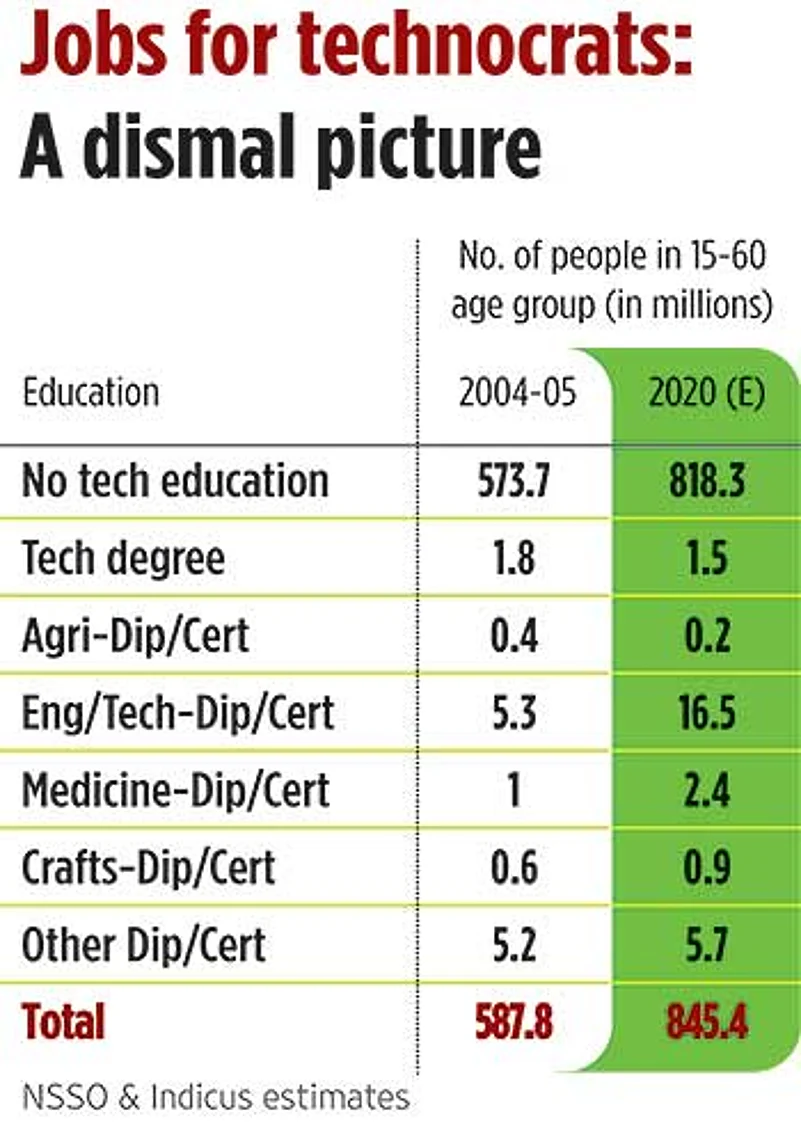

The skill-demand gap is neatly highlighted in ilr 2009: around 13 million new entrants join the workforce every year, but the existing formal vocational training capacity has been accessed by only 1.3 per cent of these—or less than 2 lakh people. Just vocational training will not do the trick either. Schools do lack vocational training, but at the same time “we must not vocationalise school education too much—the government cannot teach somebody in six months what they should have learnt in 16 years,” says Sabharwal.

A deeper look at the geographic mismatch (the previous ranking was in 2006) shows that in terms of the entire labour ecosystem—the demand and supply of jobs, and the implementation of labour laws—Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Maharashtra are at the top. However, many states losing the opportunity to differentiate themselves are at the bottom of the ranking, and these have higher chances of housing more of the poor, witnessing forced migration and social problems such as Naxalism. “Demographics is not destiny and states can bend the curve with radical programmes to improve their employment, employability and education ecosystems,” avers Sabharwal.

Cisco campus in Bangalore

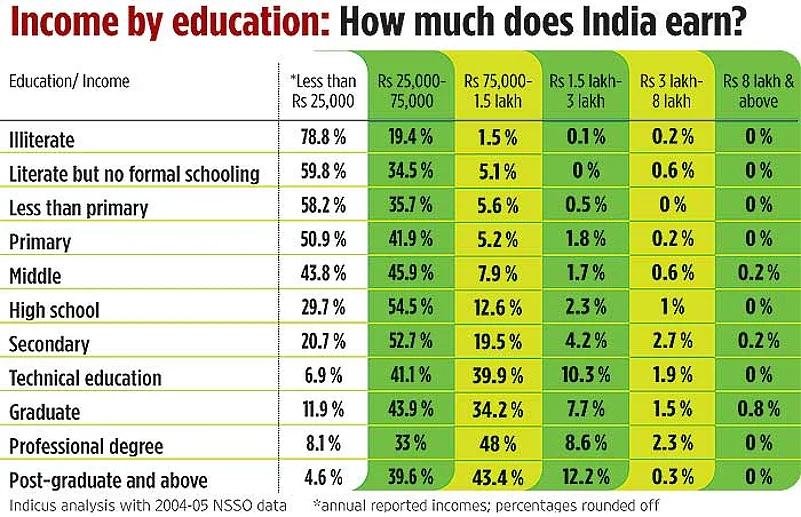

A substantial increase in capacity of vocational training, ways to enter and exit from the formal education system, and simple tools, such as allowing vocational training credits to be transferred as an “opening balance” to the formal education system, would work. But ensuring that labour gets trained in an employable, not defunct trade is also key. Besides unemployment, the “skill gap” has an unhealthy impact on livelihoods and the ability of Indians to climb out of poverty. The report finds that incomes naturally tend to rise with the higher number of years of education completed.

Delhi’s Connaught Place, abuzz with ‘executives’

“At present, what we see on the ground is that subsistence self-employment is the most prevalent form of entrepreneurship in India, which needs to be replaced by decent wage employment,” Sabharwal says. Jobs will come, but not from where we think they will. Growth is going to happen but in industries, in places and environments where not enough Indians have been trained to work in. Unless the challenges, the youth demographic upsurge and the large-scale migration out of low-paying productive jobs, are managed well on all fronts—at home, in school, and in vocational centres as well as colleges and universities—the future looks scary.