They will all vanish at the same time, like the millions of images that lay behind the foreheads of the grandparents, dead for half a century, and of the parents, also dead. Images in which we appeared as a little girl in the midst of beings who died before we were born, just as in our own memories our small children are there next to our parents and schoolmates. And one day we’ll appear in our children’s memories, among their grandchildren and people not yet born. Like sexual desire, memory never stops. It pairs the dead with the living, real with imaginary beings, dreams with history.

—Annie Ernaux, Les Années

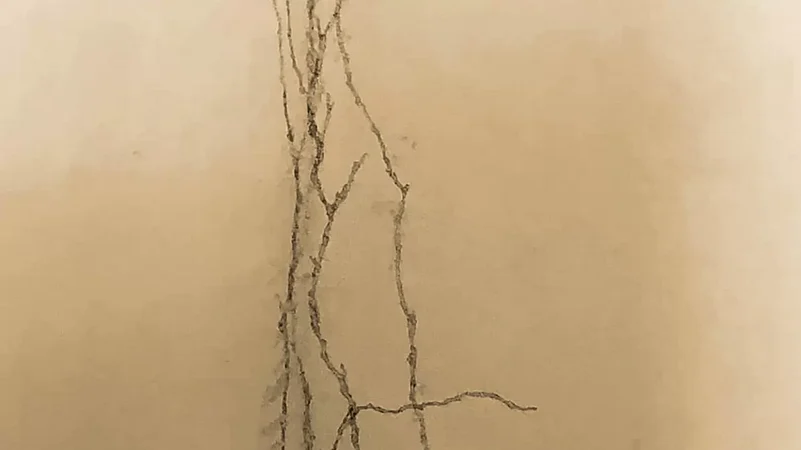

I call them veins. All these entangled pathways that line the walls of this house. Now that she is dead and gone, these termite trails remind you of the face, the neck, the arms where her veins looked like pathways to many elsewheres, imagined places she must have made up in her head to escape the dreariness of her life. It is a woman’s life and much of the memory of that life and the lives of women in the family are transferred through stories told by other women. They added their bits. Some imagined, some real. This concoction was passed down to the girls who then became women, experienced some of what their mothers and grandmothers had lived through and some wrote about these memories.

Like Toni Morrison who created a new word ‘rememory’ in Beloved in response to the tenuous nature of conceptions of history and identity and national memory and explored the issues inherent in remembering undocumented and under-documented African–American past. In an essay, Morrison said rememory referred to “recollecting and remembering as in reassembling the members of the body, the family, the population of the past”.

The interrelations of personal memory and communal history have often been explored by fiction writers to challenge narratives of the past, ones that are part of larger networks, including the media ecosystems, and patriarchal viewpoints.

Writing about memory has become more democratic in ways that democracies themselves didn’t evolve. The Nobel Prize for Literature being awarded to women like Annie Ernaux and Morrison is reassuring. We have our versions of memories and all relationships with memory are personal and political.

Ernaux has described the writing of her books ‘difficult’, ‘dangerous’, and ‘hazardous’, but she has also insisted that there was an inner compulsion to write. “Writing was only to fill the emptiness, to be able to say and to bear the memory of 58, of the abortion, of parental love, of all that was a story of flesh and love,” she writes in Se perdre. Writing enabled her to bear those memories. There must be a balance between feeling and reporting. There must be a way to write about desire, about everything else that might be in the realm of shame. Autofiction allows women to do that. It is ambiguous, rebellious, liberating.

It is an important moment for women because it recognises the power of the personal.

It shows us a way to confront and recount memories of others and our own, giving us hope. The past, when you turn towards it, is an eternity of darkness. But there are flickers of light.

Like the memory of my grandmother who passed away many years ago. I live in her room now when I visit my childhood home. In her last days, she had lost her memory and had started to crawl. My aunt took a pair of scissors and chopped off her hair that made her look like a wrinkled, feral child. I remember feeling sad about that. I try to forget my last memory of her. She had been sitting on the floor eating human turd. Her own. It has taken me years to write about it. A shameful confession.

It was last year that I decided to stay in my grandmother’s room. One of the two beds still remains. Two dressing tables have been eaten away bit by bit by the invisible destroyers called termites. I tried to salvage one. Couldn’t. There is an old wooden box where my great grandmother kept her things. It is empty now.

The termites have erased much of what belonged to the past except some memories that come in flashes. Episodic and not semantic. What is left to do but to open old trunks, doors, etc. And reconstruct, recast and reimagine and remember in order to understand who we are and how we remember what we remember.

There is an old photo of my grandmother with my grandfather on the wall. That is all there is that remains of her besides what family members took as keepsakes. I got a brass box, where she kept her betel leaves, katha and chuna and zarda. I also moved an old wooden almirah to my room in the same house but I like to stay in her room to have an audience with memories, so I can tell the story of the women in the house and in the neighbourhood, the women who grappled with a curse they only heard about and inherited. They say that in this neighbourhood, the daughters are never happy in love or marriage. They always return to live in the shadows of others.

My aunt once said there are many such women. “Look around,” she said.

And after a little pause, she looked at me. “Look inside this house. Look at yourself. Look at me,” she said.

My aunt has a great, episodic memory and when she narrates a story, you are startled by the imagery. She remembers the colour of my mother’s sari when she first saw her 43 years ago. She remembers even the 664 quality georgette white sari that my grandmother wore for her silver marriage anniversary, a white georgette sari with white embroidered flowers on it.

“Mama also wore a similar sari,” she said.

Mama was the other woman. My grandfather had perhaps fallen in love and brought home a tribal woman who went to church on Sundays and baked cakes. The ten siblings started calling her ‘mama’ after they had been told she was like their mother. Mama was a nurse and, in their old age, the two women spent their evenings together chewing paan. This I witnessed. The rest of the story I was told in bits and pieces. In their absence, only some objects remain. Like the bed. My grandmother looks a little sad in that framed photo. She is sitting in a chair and my grandfather is standing next to her. The photo shows no intimacy. They are both looking at the camera. The photo makes me sad.

One day, if I have the courage, I will write about the women in my family who learned to live without love. They spoke about their grief with each other. They protected each other. They remembered each other. They warned each other.

I inherited that sense of matrilineality, a bunch of women whose stories spanned all those years. The women formed these little friendships and drew this circle around them and I was inside it.

There are objects and there are old faded photos. There is the house itself. Then, there is the room that belonged to her with the black and white mosaic floor. Every room in that house has mosaic flooring in a different colour. My room, which previously belonged to my aunt, has red and grey mosaic; the corridors have blue and white and black mosaic; the room now nobody’s, which had once been allocated to my mother, has a yellow and peach mosaic floor. All these are continuing and disappearing threads of life. All these rooms and more are storytellers like the objects in them.

The world needs more stories about memories of women. All those stories are full of possibilities of redemption and resistance. For women and for the world. Memory never stops. Ernaux said that.

Let women write more about their memories. Fictional and otherwise. About the dead and the living.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Rooms and Their Histories")