Amrita Sher-Gil would have turned hundred this January. However, if not in person, in her work, the legendary artist remains alive and fresh in the minds of people more than ever. Generations of artists, from Sayed Haider Raza to Arpita Singh, have been influenced by her compelling works signposting a forceful modern art. A visiting dignitary like Aung Sang Suu Kyi remembered her work vividly while she was a student in Delhi. Sher-Gil has also been a beacon for women at large for her strong and empathetic works about their plight.

What is it that makes the work of the artist so significant for the present? Perhaps it is the unbearable grace of the figures, which reflected the life of people around her, touching upon the essential aspects of their lives. She returned to India in December 1934 after her training at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris, but did not join her parents immediately in Simla. Instead, she stayed for a while in her ancestral home in Amritsar, Punjab. While still there, she painted the Group of Three Girls, which depicts three young women in bright clothes. Their flamboyant costume contrasts sharply with their melancholic expressions and reflects the state of their existence. Even though grouped together, each one appears isolated and self-enclosed.

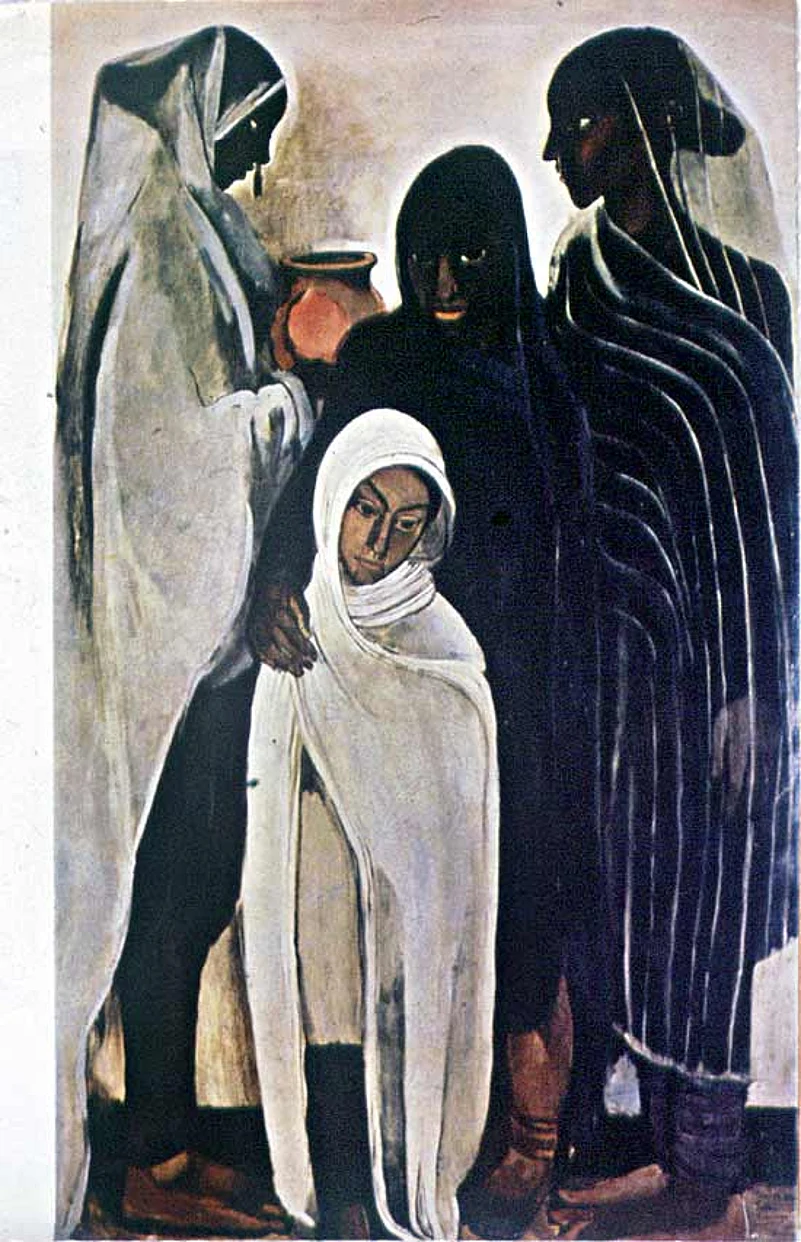

In winter that year, Amrita made two of her important paintings, Hill Women and Hill Men. The melancholy faces and thin bodies of the poor folk are transmuted into figures bearing an unutterable grace and dignity. According to Amrita, “It was the vision of a winter in India—desolate, yet strangely beautiful—on endless tracks of luminous yellow-grey land, of dark-bodied, sad-faced, incredibly thin men and women who move silently, looking almost like silhouettes, and over which an indefinable melancholy reigns....”

The fact that Amrita imbibed the traditions of the country and reinvented them to evoke the present is reflected in a spellbinding manner in her south Indian trilogy. The moulded rhythms of Ajanta begin to be assimilated in a painting like The Bride’s Toilet, made on her return to Simla. In Amrita’s painting, the fair-skinned and obviously upper-caste woman turns towards the viewer to reveal her desolation. Her keen eye for the essentials is evident in the masterly work Brahmacharis (1937), in which a group of young Brahmin boys, wearing their sacred thread and white dhotis create a composition of both nobility and vulnerability. The Brahmacharis is indeed a masterpiece, perfectly poised between the serenity of ritual tradition and the turbulence of diversity. In monumentalising the everyday, the ordinary, Amrita reached her apogee with South Indian Villagers Going to the Market. With their burnt sienna bodies and their brilliant clothes, the figures appear to have stepped out of the Ajanta cave walls to go about their everyday affairs.

Amrita had the opportunity to observe the lives of women closely, and while aware of the deeply sensuous rhythms of their lives, she also empathised with the frustrations of their truncated selves. The painting of the bride is of a woman dressed in resplendent clothes that contrast with her expression of foreboding. In Woman Resting on a Charpoy (1940), she reflects the sequestered feminine world which was her domain and became the rich ground to represent the female form layered with meaning. The plunging view of the woman lying on a bed, one hand thrown back, her legs in a position of abandon expresses all the lassitude of her existence which contrasts with her bright clothes. Verandah with Red Pillars and In the Ladies’ Enclosure also serve to bring out the grace and tedium of the daily lives of women.

If Amrita’s oeuvre evokes the tenacity, grace and utter will to survive of the people around her, it also brings out the rich traditions existing in the country, which when melded with Western forms, would lead to art highly relevant and significant for the present. Although she died suddenly at the youthful age of 28, her legacy continues to influence generations. The large collection of her works at the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, donated by her husband, the late Dr Victor Egan, after her death, bear witness to this fact. Streams of visitors come to see these paintings, being impacted by their strong artistic value.

(Dalmia’s biography Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life has been published by Penguin as a paperback to mark the artist’s birth centenary.)