A small caravan of tractors trickling in towards Delhi on NH44, armed with nothing more than slogans and unbending intent. Under usual circumstances, they would have become just another sector of protest—no shortage in India of those. But as the days went by, they built up such gale force behind them as to recall a medieval army, the sort that could decide the balance of forces in history. The proud but care-worn faces of Punjab’s farmers—those who sired India’s Green Revolution—have by now sown a perfect political storm, confronting the NDA government head-on, becoming one of the very few who could compel it to blink.

Since December 1, the Centre has appeared on the backfoot—going through five rounds of negotiations with 40 farmer union leaders, saying it was open to amendments in the new farm laws, even considering a special session of Parliament to get statutory sanction for the changes. Ten days later, though, the script is stuck as the maximum offered does not match the minimum demanded. After all the labour, for both sides, often operating across a gulf of trust and belief systems, the harvest is delayed.

ALSO READ: Minus And Maximus

That things were headed for a difficult impasse became clear on December 8, the very day the farmer unions called a moderately successful Bharat Bandh across the country. Union home minister Amit Shah had stepped in for the first time, holding four-hour-long talks with 13 farmer union leaders, but ruling out a full repeal of the three new agri-laws, passed by Parliament during the monsoon session in September. The NDA government instead offered a fresh proposal: giving it in writing that it would build in amendments to the laws based on the farmers’ demands. That reluctance to repeal had coloured the previous rounds of meetings too, but Amit Shah expressing it conveyed an extra degree of finality.

The talks faltered—the sixth round, slated for December 9, was postponed. Instead, both sides decided to confer internally—at a morning cabinet meeting and at the farmers’ new caravanserai, the Singhu border. On Wednesday, December 9, a joint meeting of farmer unions at the latter venue, expectedly, rejected the rejection, so to speak. Nothing short of a full repeal of the three farm laws and the Electricity Bill 2020 by way of an immediate ordinance and later through a special session of Parliament, they said.

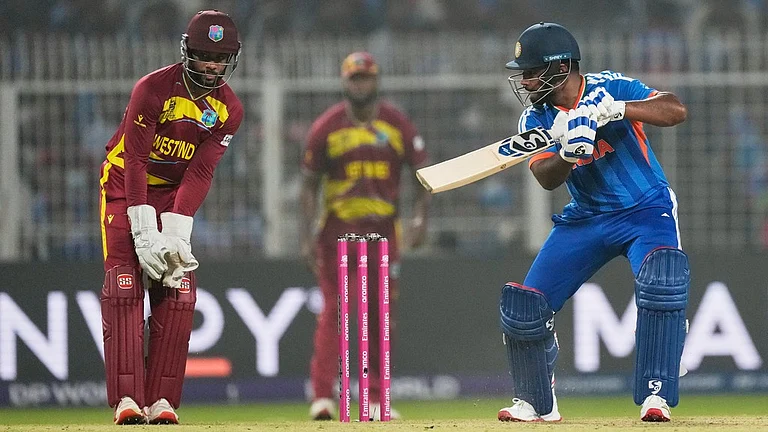

Early December—as farmers converged on the Delhi border, clashes broke out with cops .

This line of total defiance was delineated by Hanan Mollah, former Lok Sabha MP and general secretary, All India Kisan Sabha, a CPI(M)- affiliated farmer union, with the words: “There is absolutely no scope for any amendments, we want a repeal of the three farm laws.” Yet, there’s some internal variegation of views. Privately, some farm union leaders like Rashtriya Kisan Mahasangh national convenor Shiv Kumar Sharma, aka Kakkaji, who realise the Centre may not budge, say: “Although our public stand is a full repeal, we can negotiate provided the government is ready to provide remunerative Minimum Support Price (MSP) as a legal entitlement to all farmers for all produce.”

ALSO READ: ‘New Laws Not Related To MSP’

Even so, that’s just a degree of difference on the bargaining approach: the thing bargained for is the same. How did India’s farmers—a vast, disaggregated population, fighting a prolonged existential crisis and with no sustained voice in policy—attain this level of organisation and unanimity?

The killing of six farmers in June 2017 at the protests in Mandsaur, Madhya Pradesh, was a tipping point. India’s isolated farmers’ movements started coming together after that—coordinating, forming coalitions across groups, gaining considerable strength from that unity. The creation of the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee (AIKSCC) has been a very significant development in the history of farmers’ movements, says V.M. Singh, its convenor.

ALSo READ: Minimum Support, Maximum Mileage

And yet, coordinating between hundreds of farmer unions—each with a divergent agenda, or different ideological position—poses a gigantic problem. At one level, there are 30 unions from Punjab, who form the heart of the siege at Singhu. Then there’s the AIKSCC at the national level, with a working group representing over 300 groups, including 10 of the Punjab unions. Then there’s the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM), a coordination body between the Punjab groups, the AIKSCC, the Rashtriya Kisan Mahasangh (RKM), different factions of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU Chaduni, BKU Rajewal and almost 38 others), says Binod Anand, founding member, Rashtriya Kisan Manch. To understand the landscape of protests, one must negotiate this alphabet soup.

On November 3, about 50 farmer leaders from across India met at Delhi’s Rakabganj Gurudwara and selected 10 leaders to form a coordination committee of the SKM to represent farmers at talks with the government: five RKM leaders and five from the AIKSCC. The first five were Shiv Kumar ‘Kakkaji’, Jagjit Singh Dalewal, Gauri Shankar Bidhura, Harpal Singh Billari and Swami Indradeo from one of the BKU factions. Initially, Yogendra Yadav, V.M. Singh and three others were selected from the AIKSCC. Later Yadav and Singh were replaced with Hanan Mollah, and Rakesh Tikait of BKU (son of late BKU leader Mahendra Singh Tikait) joined along with Yudhvir Singh. By the third meeting, Kavita Kuruganti from AIKSCC was in the talks, representing the South by way of Karnataka.

ALSO READ: Sow Only After Preparing Soil

On November 5, a Bharat Bandh was announced by the two bodies together, and the show of solidarity began. On November 13, two meetings were held, one in Vasant Kunj and another again at Rakabganj Gurudwara, where the basic agenda was hammered out: about half-a-dozen demands. On November 26-27, the idea of the Delhi siege was born. Since December 1, the Samyukta Kisan Morcha leaders began negotiating with the NDA government, representing 30 farmer unions from Punjab and Haryana and hundreds of others from Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Kerala and other southern states.

During the negotiations, some tensions and ideological differences appeared, especially between the left-wing AIKSCC members and the right-wing RKM members. AIKSCC leader Kavita Kuruganti says it’s natural and actually a sign of robustness. “There are always small differences in a coalition of this massive size. But you must recognise the sheer scale and diversity of this movement. It is unprecedented that so many different groups, from different areas and different constituencies, even different politics, have been willing to join hands and coordinate. It is a credit to the seriousness of the cause,” she says.

What makes the farmer unions unique? “It is the preparedness and peaceful resolve of the diverse farmer unions, despite all provocations, to stay put until their demands are met. The evidence of preparedness is the long queues of tractor trolleys, trucks converted into spacious rooms with warm beddings, everyone ready to survive the chill of the severe winter out in the open. The farmers have also come prepared with food rations and have refused to eat any food offered by the government. Instead, they prefer to eat at langars offered by the gurudwaras. The camaraderie is extraordinary: protesting farmers have the support of fellow farmers back home who ensure that wheat and other crops are sown in time and tended to while the protesters continue to struggle at the different borders of Delhi. The support pouring in from all sections of society is simply amazing,” says Kuruganti. It’s a massive mobilisation, a virtual siege of the capital city at four borders: Singhu, Tikri, Jharoda and Chilla. All four shut without any violence: just like the negotiations.

A Federal Failure

Why such inflexibility? A legal reason can explain the unbridgeable gap between the laws and those it affects. Some constitutional experts say the three agri-laws violate the federal character of the Indian Constitution. Agriculture is under the purview of the State List and the Centre has no jurisdiction to rule over agriculture even under the Concurrent List. Says K.T.S. Tulsi, MP and senior advocate: “This is an attempt by the Centre to usurp powers explicitly given to States under Entries 14, 18, 46, 28 of the State List. These three new Farm Acts lack a legal framework the way they came into existence. They deprive states of their revenue via any cess or levy. Therefore, they are a challenge to the separation of powers that forms the backbone of Indian democracy.”

The Acts also come up short in their dispute resolution provisions, Tulsi argues. “(They) fail to lay down who can represent the parties in a dispute. The Act goes on then to overburden an already overworked sub-divisional magistrate (SDM) in the absence of such a conciliation process being elucidated. The most inhumane of all provisions are those that take away the right of appeal from a farmer. The State, exercising its power through multiple bureaucrats, seems to have elevated itself to the status of God, its decisions immune from challenge. There is a glaring absence of any power being given to the farmer if the decision delivered is biased, a product of corruption, prejudiced or simply a manifestation of the said authority’s bad mood.”

We Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere—a hukkah here, police helmets there, catching the news, checking the tractor rearview, a health check (it’s Covid time and social distancing is far off anyone’s mind on a protest site), piping hot bhatures…the farmers have dug in their heels.

Historical Echoes

But sometimes the ground insists on its mood being given precedence. The historic parallel is clear to all those old enough to remember: a similar siege of Delhi was organised by farmers 32 years ago, for a week beginning from October 25 to early November, 1988. Almost five lakh farmers, mainly from western Uttar Pradesh, virtually swamped the protest site of those days, Boat Club lawns, filling the entire stretch from Vijay Chowk to India Gate—a shouting distance from North and South Blocks and Parliament, where the winter session was about to begin. Led by Mahendra Singh Tikait, the charismatic BKU leader, they had a long list of 35 demands—including higher prices for sugarcane, waiving of electricity and water charges. The Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress government, in power with a brute majority—almost 60 MPs more than the present Narendra Modi government—ultimately succumbed.

“Yet, the BKU was largely a regional force confined to western UP,” says Prof Zoya Hasan, who has researched the Tikait-led movement threadbare. “In sharp contrast, the current movement is much more ambitious, a pan-Indian phenomenon, a much larger canvas.” Their social composition is very different too, she says. “The BKU movement was preponderantly led by Jat farmers from Muzaffarnagar, Meerut and other western UP districts, although the BKU did have broad support from other castes among farmers. The current movement is a loose, cross-cultural rainbow coalition—farmers from different states, cutting across multiple castes, multiple classes,” she says. Given this internally variegated character, it’s no surprise to find contrasting ideologies cohabiting under one umbrella. Some figures, like Hanan Mollah, are affiliated to the CPI(M), quite a large contingent from Madhya Pradesh and other central Indian states is affiliated to the AIKSCC, many from Punjab were affiliated in the past with the CPI(ML). Plus, there are the 40-odd groups descended from Tikait’s BKU. Kakkaji began his political activism with the RSS in Madhya Pradesh.

This wide social base also gives a pan-India colour to the veto it offers neoliberal economics—which the three laws passed by the NDA embody. Says Prof Manoranjan Mohanty of Delhi University: “This is the first major effective challenge to the NDA regime in the last six years. The anti-CAA protests were widespread but fizzled out due to the pandemic. The current protests are pan-India, have a multi-class character.” The latter bit is also a point of contrastive analysis for him, compared to key peasant movements of the past, such as the Telangana movement in 1946 (which was primarily confined to Warangal and Bidar), the Tebhaga movement led by the CPI-affiliated Kisan Sabha in 1946-47 in Bengal, the 1921 Moplah rebellion of Kerala and the Naxalite movement of the ’60s-70s. Those were, by definition, “peasant movements…the participants were mainly farm labourers and small farmers. This movement includes farmers from all sections, poor and rich,” says Mohanty.

Despite the support of 24 Opposition parties, there’s a disconnect at the ground level between the farmer’s movement and electoral politics, admits Hasan. Although over 65 per cent of India’s voters are rural, farm issues mostly never become a dominant agenda in Indian elections, points out Sanjay Kumar, director, CSDS. Reason: farmers are divided over identity issues such as caste, community, religion et al. But the groundswell of support this time is forcing the NDA government on the defensive, says Mohanty.

An eclectic, regionally diverse character is not the only difference. Media itself has exploded—and that makes for a force-multiplier. Binod Anand recalls that the 1980s offered only the print media, plus state-run Doordarshan and BBC. Today’s movement is being covered 24x7—there are, literally, hundreds of TV outlets and thousands of social media platforms. If the former elicit charges of pro-establishment bias, the latter make amends. “Consider the popular hashtags: #FarmerDilliChalo, #TractorToTwitter, #StandWithFarmer, even #BoycottAdanisAmbanis. Preparing press briefs for such a large and diverse media contingent in several languages is a tremendously challenging job,” admits Anand.

A World of Protests

All that social media also creates another factor: things do not stay local. A massive show of support flowed from the Indian diaspora in the US, Canada, Europe, Australia and elsewhere. Hundreds of Indians living abroad signed online petitions. About 36 British MPs sent a joint letter to British foreign secretary Dominic Raab. And, catering to his own large Punjabi voter base, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau became among the first world leaders to express support for the farmers’ right to protest, reiterating his words on December 4. “Canada will always stand up for the right of peaceful protest anywhere around the world. And we’re pleased to see moves towards de-escalation and dialogue,” Trudeau said. It was not uncontroversial. India issued a demarche saying such remarks could damage bilateral relations and external affairs minister S. Jaishankar skipped a Canada-led meeting of foreign ministers on December 7. But Punjab’s strong cultural links with diasporic populations had by then set a narrative New Delhi could scarcely ignore. Downtown Toronto, Saskatoon, Halifax in Canada; Indianapolis, NY, Chicago, DC in the US; ‘India stop selling off your farmers’ placards across the Atlantic in central London; Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra down under. Northern California, which has large concentrations of Sikh and Punjabi origin populations in Yuba City and Stockton, saw a kisan car rally block traffic on Bay Bridge. But the global heart of all this, undoubtedly, was the remarkable traffic block at Singhu, on NH44, at the gate of Delhi. How long that endures may affect the shape of India’s politics and economics.

***

Contentious Laws

1. Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation Act 2020

- Barrier-free trade outside APMCs

- No licence required to buy/sell

2. Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Prices Assurance and Farm Services Act 2020

- Creates framework for contract farming between buyer and farmer

- Three-level dispute settlement mechanism: conciliation board, sub-divisional magistrate and appellate authority

3. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020

- Removes cereals, pulses, oilseeds, edible oils, onions and potatoes from list of essentials

What farmers want/fear

- Repeal the three laws by calling a special session of Parliament

- First law will give entry to corporate agri-business

- Second law will destroy APMCs

- Third law will lead to price fluctuations (Example: potato prices shot up from Rs 20 before-Bill to Rs 70 after)

- Provide remunerative MSP as legal entitlement for all produce

- Withdraw all cases against farmer activists

- Withdraw electricity amendment bill 2020

- Exclude farmers from purview of air quality commission ordinance for Delhi air pollution

Centre’s stand

- Committed to implementing MSP, but no legal guarantee

- Will implement amendments, but will not repeal farm laws

- Considering special session of Parliament, but no official announcement yet

- Prepared to talk with farmers to resolve impasse