Amid the deafening political rhetoric of assembly polls and horrific cries of Covid-induced pain and suffering elsewhere in the country, a milestone in India’s contemporary political history went completely unmarked on April 5. It was on this day a decade ago that a self-acclaimed Gandhian from Maharashtra’s Ralegan Siddhi village sat on an indefinite hunger strike at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar. Public anger was simmering against the Manmohan Singh-led UPA government. Allegations of corruption and malfeasance against senior ministers and high-ranking bureaucrats in everything, from defence deals and Commonwealth Games to coal blocks and telephone spectrum allocation, were tumbling out of the Comptroller and Auditor General’s (CAG) ledgers. Investigation agencies—primarily the CBI—were getting slammed for protecting those in power. Singh was under attack for an alleged conspiracy of silence, criticised for being a puppet controlled by Sonia Gandhi, leader of the ruling UPA coalition and its largest constituent, the Congress party. The common Indian was frustrated and angry—she battled skyrocketing retail inflation and rising unemployment while those in power were allegedly rolling in millions of rupees in black money.

ALSO READ: Twice Orphaned

Over the next two years, each time the man returned to Delhi for his fast-unto-death, dressed in his austere dhoti-kurta and Gandhi topi, the government was on its toes. Flanked by a motley group of disciples—activists, lawyers, a former top cop, a yoga businessman—and streamed live on television screens round-the-clock by news channels, the man at Jantar Mantar offered a miraculous solution—Lokpal—a panacea for India’s crippling political and institutional rot. The stirrings of an inquilab or revolution were palpable; the man’s lieutenants claimed they would free so-called autonomous institutions from political control.

For countless Indians who were mesmerised by the anti-corruption campaign, the movement also meant something of far greater significance. Activist Mayank Gandhi, who was part of the Lokpal movement in those turbulent days tells Outlook: “The aandolan struck a deeper chord… we were tired of seeing constitutional bodies and so-called independent institutions compromised by those in power.” Gandhi says the proposals of a public charter and to make politicians, bureaucrats and the judiciary all accountable to the Lokpal “flowed from a belief in the need for institutions that are truly autonomous and independent in practice and are answerable to the public and not the power elite.”

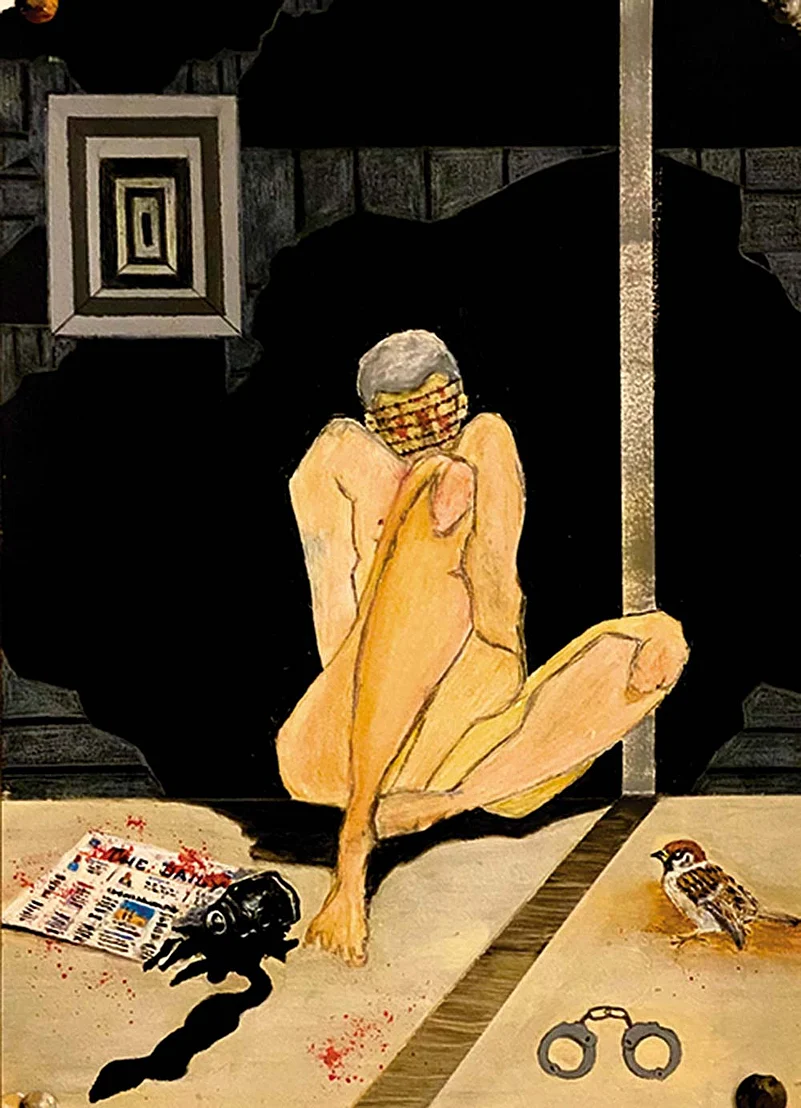

ALSO READ: The Empire Of Cruelty

The Lokpal got legislative sanction on January 1, 2014, though with vastly reduced powers than were originally envisaged. Five months later, the UPA government lost power. The Congress was reduced to its lowest tally ever in the Lok Sabha and the BJP, led by Narendra Modi, stormed into office. The man at Jantar Mantar receded into the shadows, several of his lieutenants plunged into the very system they once claimed they would change, some of them were now enjoying the fruits of political power they once claimed to abhor.

In 2019, after several nudges from the Supreme Court, the Lokpal actually became functional with former Supreme Court judge, Justice P.C. Ghose, becoming the country’s first anti-graft ombudsman. The notion of a Lokpal ending corruption in public offices, however, proved highly illusory. According to official data, the Lokpal received just 95 complaints in 2020-2021, of which 66 were closed at various stages of preliminary investigation. The data from 2019-2020 is equally baffling: the Lokpal received a total of 1427 complaints of which 1218 were dismissed on grounds that they were beyond the ombudsman’s jurisdiction; directions for action were given only against 34 complaints. The miniscule number of anti-graft complaints is difficult to reconcile with India’s performance on globally well regarded indices such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). After a marginal improvement in its CPI ratings in the initial two years of Narendra Modi’s government, India has consistently been slipping on the index since 2017, currently ranked 86th out of 180 countries.

ALSO READ: The Seventh Seal

Meanwhile, the larger dream of the Lokpal movement—true autonomy of institutions—was quickly forgotten. Instead, institutions now appear to be under far greater strain than they were during the preceding years. Earlier this year, the Narendra Modi government tried to fend off criticism over India being downgraded in the US-based democracy watchdog Freedom House’s Freedom in the World, 2020 report. India’s ranking slipped from being a “free” nation to a “partly free” one on Modi’s watch, but there were more causes for worry.

ALSO READ: The Complete Covid Chargesheet

India performed poorly on parameters such as independence of the judiciary, extensive political indoctrination in the education system, safeguards against corruption and India’s failure to uphold due process in civil and criminal matters. An excerpt on the independence of judiciary was particularly damning. “The score declined from 3 to 2 because the unusual appointment of a recently retired chief justice to the Upper House of Parliament, a pattern of more pro-government decisions by the Supreme Court, and the high-profile transfer of a judge after he ruled against the government’s political interests all suggested a closer alignment between the judicial leadership and the ruling party,” the report said.

The view that the judiciary, particularly apex, has become committed to the cause of the government, and not justice, has been debated often. In an interview to Outlook earlier this year, retired Supreme Court judge Justice Deepak Gupta had candidly admitted that “one does feel that a perception is building up that the court does more to favour the government than the public at large.” From the infamous judges’ press conference of January 2017 onwards, the ominous import of this notion has been that successive chief justices of India, other judges and their judgments often get viewed with suspicion of political complicity. Similarly, decisive and timely interventions by the judiciary, as seen in recent weeks in the Covid pandemic management and inoculation-related cases, get applauded as exceptions when they should be welcomed without riders.

ALSO READ: Union Of Federal Uncooperative

A double whammy for the judiciary also comes from the perception that judges in its higher echelons are appointed not purely on merit but also on political considerations. Justice Gupta says, “If you are a very independent-minded judge in the high court and are not soft towards the government, the government will thwart your elevation as CJ or as judge of the SC.” There have been several past instances that attest to this fact, most notably that of the Centre’s resistance to elevating Tripura high court chief justice, Justice Akil Kureshi, to the SC. The SC, which has a sanctioned bench strength of 34 judges, currently has seven vacancies.

That the Modi government is “destroying the framework of all institutions that hold up a democracy, including the media and the judiciary” has been Congress leader Rahul Gandhi’s most relentless criticism of the ruling dispensation. This criticism has been equally applicable to past Congress regimes in varying degrees. Successive Congress governments were culpable of trying to influence the media and investigation agencies—the SC’s “caged parrot” appellation was coined for the CBI in 2013 during the UPA era— and of packing various national commissions and academia with ideological fellow-travellers. Yet, the taint of institutional capture, or institutional collapse as some call it, sticks strongly on the Modi regime. “Can you name any constitutional body or autonomous institution that isn’t acting like an extension of the government today,” asks Congress spokesperson Gourav Vallabh. Old allegations of swift erosion in the credibility of law enforcement agencies such as the NIA, CBI, ED and DRI among others have returned like the more virulent second wave of Covid; made believable by the prompt targeting, arrests and incarceration of anyone who espouses politics and ideology that differ from the BJP’s. Public intellectuals in the Bhima Koregaon case, students of JNU, Aligarh and Jamia Millia universities, student-activists in the anti-CAA protest and Northeast Delhi riots cases and prominent politicians like P. Chidambaram and D.K. Shivakumar—examples are aplenty. The most discredited of these agencies—the CBI—witnessed high drama between October 2018 and January 2019 when the Centre sent then CBI director Alok Verma, who was reportedly planning to open a probe into the Rafale jet deal, on leave and then sacked him.

ALSO READ: ‘Modi Brought India To Its Knees’

Other institutions such as the CAG, the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) and the Central Information Commission (CIC), which were regularly in the news for their criticism of the UPA regime, are rarely heard of now. “A major cause for the UPA’s loss of credibility among the people was the embarrassing reports and missives that came from institutions like the CAG, CVC etc. Then CAG (Vinod Rai) had become a household name, his reports forced several Union ministers to resign… today no one knows who the CAG is or what he is doing,” says former law minister Veerappa Moily. The last time that a CAG report created some public interest was arguably the audit of the controversial Rafale jet deal—not for the revelations but for those it concealed. “The CAG’s Rafale audit report was placed before the Supreme Court after redacting prices... have you ever heard of an audit that doesn’t declare the price of the commodity being audited,” asks the former law minister. Institutions of learning like JNU and Jamia, among India’s top universities despite a vicious smear campaign, are under siege too. Activist and a JNU alumnus, Sohail Hashmi, says: “Recurring instances of campus unrest across the country, attacks on students by BJP goons, foisting of sedition cases against student activists and appointment of pliant and compromised vice chancellors to various universities prove this.”

The people’s expectations from that dharna at Jantar Mantar a decade ago were clearly misplaced. The resounding electoral verdict that their outrage caused seven years ago—and its amplified version two years back—too failed in stemming India’s institutional rot; arguably it’s worse off today. Jantar Mantar, meanwhile, is quiet and so is the man who screamed Inquilab Zindabad from the stage there 10 years ago.

ALSO READ: