Nationalism is often viewed as contrary to liberalism in contemporary political and social narrative. Post-World War II global discussions on the emergence of nation states and the progress of political dispensations in ensuring guarantee of human rights assumed greater importance. The international human rights movement also gained currency at this time. The United Nations became the torch-bearer of such a movement. The UN Charter promised “inherent dignity” and “equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family”—this guarantee of dignity of life to every individual who is a global citizen transcends geographical boundaries of the nation states. The UN made it mandatory for every one of its missions and activities to uphold these human rights principles as “the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world”.

Yet, at the global level, human rights as applicable by UN standards began to be measured through covenants and conventions within the parameters of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All the Migrant Workers and the Members of their Families (CRMW), euphemistically called the International Human Rights Convention adopted in 1990 in the background of globalisation. There is perceptible contradiction between the nation states jealously guarding their political turf and sovereign rights and the international body seeking to ensure and guarantee global human rights. Does the ‘rule of law’ as agreed upon and understood as being inviolable link between nation states encompass the global protection of private individuals against one’s own government? Is there a global citizen and does his or her rights as a human being supersedes the bounds of nationhood?

ALSO READ: Silent Alarm

A quick overview of the history of the United States will reveal the stark reality of how uncomfortable the “global cop” was with this idea of universalist and internationalist approach to individual freedom and human rights of a private citizen. After dodging the issue for decades, the US Senate finally ratified the UN human rights conventions as late as in the eighties only after securely insulating its domestic laws from these international transgressions. The supportive argument to this thought process was that laws framed by national authorities to protect human rights cannot be subject to review by an international authority.

Nationalism, as it is understood today, is not considered to be an idea that is older than eighteenth century history. According to European scholars, the French Revolution was the trigger that added dynamism to this idea and hastened the process of evolution of the concept of nationalism, closely embracing the ideas of individual freedom, human rights and egalitarianism. This explanation ran concurrent to the premise that a total revision and restructuring of the relationship between the ruler and the ruled and between the classes and the ‘estates’ in the society are germane to the strengthening of nationhood. With the third estate acquiring power, nationalism came to represent a new class and its interests limiting the idea to a process of integration of people into a common political framework. Needless to say, this progression of the concept of nationalism presumed the inevitability and importance of a centralised authority reining over the people in a specific geography requiring total surrender of individual rights and identities to a pool of common identity.

ALSO READ: Floydian Slip

Crafting a global framework for determining the parameters of human rights, solely based on the understanding and explanations of the European and so-called Western scholarship of the concepts of nationalism, nation states and individual rights and their correlation with one another has its own inherent limitations. More importantly, trying to superimpose these parameters on a country like India and then assess the evolution of the process of emergence and development of the idea of nationalism, social cohesion and individual rights and freedom would lead to misleading conclusions. It is important to note that in the Indian thought process there is no conflict between nationalism and internationalism, between domestic laws and international conventions when it comes to guaranteeing and protecting human rights within the political, national or cultural parameters. The emergence of the idea of providing sovereign guarantee to human rights and individual freedom as opposed to religion has its roots in the historical emergence of the modern state as a deconstructive movement against the theo-political order of Medieval Christian Europe.

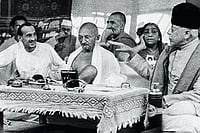

In the Indian context, during the British rule, the colonial masters went to great lengths to dissipate the feeling of nationalism from the minds of the people. Hence, for those who were leading the freedom struggle, it was important to understand this aspect and link the freedom struggle to the philosophical roots of our socio-cultural existence. The struggle against British colonialism necessitated taking recourse to nationalism and the organisation of society on the basis of one nationhood, one people and unity of purpose. Three contemporary viewpoints, seemingly different but in essence meaning the same thing in different words, were echoed by Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Ambedkar and the founder of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) Dr. K. B. Hedgewar. They all believed in inclusivism, human dignity and humanism.

ALSO READ: Our Wronged Rights

Mahatma Gandhi was not being apologetic when he appealed to the nationalist sentiments of the people to offer satyagraha against the British. “It is impossible for one to be internationalist without being a nationalist. Internationalism is possible only when nationalism becomes a fact, i.e., when peoples belonging to different countries have organised themselves and are able to act as one man. It is not nationalism that is evil, it is the narrowness, selfishness, exclusiveness which is the bane of modern nations which is evil. Each wants to profit at the expense of, and rise on, the ruin of the other. Indian nationalism has, I hope, struck a different path. It wants to organise itself or to find full self-expression for the benefit and service of humanity at large,” he wrote in Young India. (Young India, 18-6-25, p. 211 https://www.mkgandhi.org/voiceoftruth/nationalism.htm)

When Rabindranath Tagore questioned the idea of nationalism and placed individual freedom and right as a human being to be superior to that of a collective political order, he was actually challenging such a superimposition of a Western idea on Indian entity. Tagore thus questioned the western concept of the nation, which explains a nation, in the sense of political and economic union of the people, which a whole population assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose. He argued that society as such has no ulterior purpose and is an end in itself. “It is a spontaneous expression of man as a social being, a natural regulation of human relationships, so that men can develop ideas of life in cooperation with one another. It has also political side, but this is only for a special purpose. It is for self-preservation,” he wrote. Tagore is very clear that a naturally-built human society is much more humane in essence than the artificially created nationhood.

ALSO READ: Rights Of Nature

The founder of RSS Dr. Hedgewar believed that we are an ancient nation united by culture, common historical experience of successes and failures, victories and defeats and have a common identity and aspiration. This collective desire for Independence was the objective of all those who were leading the freedom struggle but on different paths. Dr. Hedgewar strongly believed that efforts to unite the Hindu society are as important as achieving political freedom without compromising with the core principles on which the socio-cultural edifice of the country was founded on.

The complexity of understanding the RSS comes from the fact that the term Hindu was and continues to be a flexible idea. It could be explained as a cultural denomination which includes multiple methods of worship and philosophical streams. It could also be understood as a civilisational identity that goes far beyond the colours and conventions of religious practice.

ALSO READ: Of Rage, Courage And Democracy

The intellectual impetus behind the RSS has a justification which is in congruence to the Indian thought pattern (a better word would be darshan) and philosophical systems. As a result, although western notions of human rights are important, they are not essential for the advocacy of social reform in India. Hence, the RSS has been humane in its approach towards the marginalised and less-privileged sections of society without using a political form of rights-based approach but instead, using the vastness of the philosophical foundations of the Sanatan Dharma. For the RSS, spiritual dictates such as “aatmavat sarva bhuteshu” (treat all existence as manifestation on self) are the basis of social framework and building blocks for an egalitarian and just social order supported by a democratic political dispensation. While the logical origins of the western concept of human rights has its roots in the theological foundation of Abrahamic religions, the Indian viewpoint of human rights flows from the philosophical basis as articulated by various philosophical schools.

The Indian Constitution envisages a welfare state where human rights, social justice and economic opportunities should form the core objectives of any government. The RSS believes that this aspect of the Indian Constitution like many other provisions reflects the ethos and captures the spirit of the ancient collective wisdom as propounded and passed from ages. There is no conflict between nationalism and internationalism, between individual freedom and collective obligation, between inclusivism and diversity.

(Views are personal)

ALSO READ:

Seshadri Chari is an RSS ideologue and former editor of Organiser