Politics makes surprising things happen. Even Narendra Modi can cite the Bible. It happened in Kerala, of course, on March 30. The prime minister was addressing an election rally in Palakkad, a district that hosts some of the high passes that take you across to Tamil Nadu. His point of reference was Judas, the arch figure of betrayal in biblical lore. And who did Modi wish to compare him to? The LDF government in Kerala, who else? The ironies that abound in Indian democracy today exceed the fact of the Hindutva icon citing a Biblical character, one who had betrayed Christ for a few pieces of silver, to a party that has spent decades trying to speak a godless politics. Till recently, of course. Because divinity, and the ways in which society approximates to it, is a political issue these days. The prime minister, on the campaign trail in poll-bound Kerala, also raised the Sabarimala temple issue, slamming the Pinarayi Vijayan government on its handling of the agitation following the Supreme Court verdict allowing the entry of women of all ages. Lord Ayyappan and Jesus Christ thus came together in 21st-century India.

The same day, amid loud chants of ‘Jai Shri Ram’, Union home minister Amit Shah also held a massive roadshow in far-away Nandigram, in the western part of West Bengal, where the canonical Bengali society begins to shade off into Adivasi territory. This edgeland has been part of Indian political lore for a decade now; you could hear its name being thrown about even in Malayalam films, as the place that defied even a Left regime when they tried to mess with people’s ownership of land. This is where Suvendu Adhikari, the recently saffronised leader who was on the frontline of that battle, is now taking on his mentor of those days, Mamata Banerjee. It’s a do-or-die battle. He shows no mercy for his former leader—he even called her the ‘phuphu’ of infiltrators and the ‘khala’ of Rohingyas. Phuphu means paternal aunt, and khala means maternal aunt—both are words used mainly by Muslims. And then he cautions the voters: “If she wins, you won’t be able to put a ‘tilak’ on your forehead, wear tulsi beads around your necks, or even don a dhoti.” The references are hardly subtle these days.

ALSO READ: A Battle For The Hindu Mind

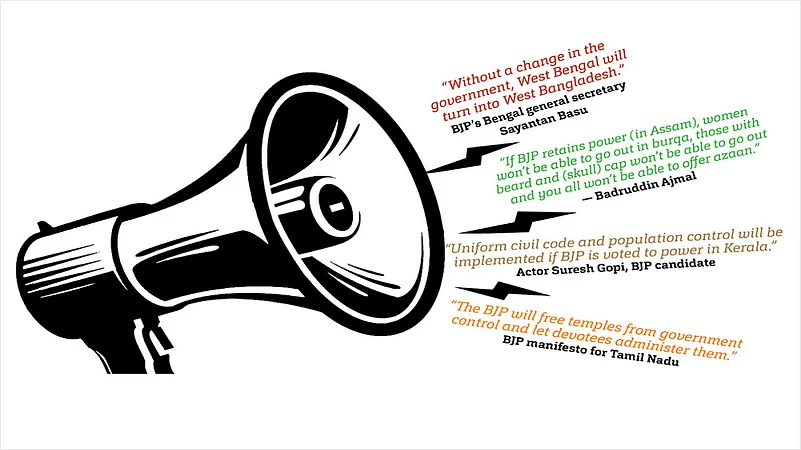

Amit Shah, who has emerged as a star campaigner for the BJP, has also promised the people of Assam (which has a 36 per cent Muslim population) freedom from the “menace of love and land jihad”. The target there is mainly the Congress, which is contesting in alliance with the AIUDF, led by perfume baron Maulana Badruddin Ajmal. That the latter is a “Muslim” party enables the accusation that this alliance encourages infiltration from across the borders.

It’s not just Kerala, Bengal and Assam. Sparks of Hindutva seem to have touched Dravidian politics too, with issues of faith and temples becoming talking points even in the Tamil Nadu polls. Even the DMK, a party with a history of avowedly anti-god politics, has been making poll sops for temples and devotees. The AIADMK, which has been in such deep alliance with the BJP that it could be seen almost as a proxy, is hardly impressed. Targeting his rival M.K. Stalin on the subject of faith, Tamil Nadu CM K. Palaniswami claimed, during a campaign speech on March 29, that AIADMK members were true believers. He recalled the incident when the DMK leader had allegedly “wiped off” kumkum from his forehead after a temple visit in 2018. This is the state of political discourse in Tamil Nadu, where a form of ‘rationalism’ has been the credo for a century.

ALSO READ: God Finds Place In Own Country

The BJP’s rise in recent decades has brought feelings about Hinduism to the forefront from the subliminal levels where they always existed. Under the Modi-Shah regime, it’s become overt. The persistent pursuit of electoral wins by the BJP since 2014, and the unapologetic and successful deployment of Hindutva as a weapon, has changed the contours of competitive politics in the country. It is evident that other parties have recognised the compulsions and have been forced to change tack.

Look at Mamata Banerjee. She is now asserting her Hindu Brahmin identity, reciting the Chandi path, the Durga path, and visiting temples with fervour. The Hindutva space is getting crowded. Congress leader Rahul Gandhi had shown the first signs of how the narrative is flowing back in 2019, with his famous pre-poll ‘temple run’. That didn’t yield much dividends. Now, he seems to have given up on projecting his party as that of ‘better Hindus’. The nervous aversion to displaying their ‘secular’ credentials is in the past. That’s why the Congress has aligned with Badruddin in Assam and the Indian Secular Front (ISF) in West Bengal; the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) in Kerala was always an ally. The Gandhi scion has now taken to flaunting his abs instead of his janeu (sacred thread) to woo the youth.

ALSO READ: Sharp End Of A Poll Spear

The broad pattern is clear: the ongoing campaign for the assembly elections in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Assam and the union territory of Pondicherry has brought to the surface the layers of polarisation that exist in Indian society, and have sharpened and deepened them through the language of electoral politics. The references are chiefly to religion, but also to regional identities and caste. It has gone beyond the Hindu-Muslim binary. The narrative now encompasses other religions, like Christianity in Kerala. And also castes like the Nadars of Tamil Nadu, communities like the Matuas, Kurmis and Rajbongshis of West Bengal. It also plays overtly on regional identities—Assam is a case in point.

Social historian Badri Narayan believes there has been a paradigm shift in the BJP’s polarisation strategy—the overt and aggressive play it is making for Bengal is a prime example. “Actually, describing it as polarisation may not be correct…that is now an older tactic for the BJP. The party has not gone for Hindu-Muslim polarisation. Instead, it has opted for mobilisation based on caste and community—bhadralok and non-bhadralok. The party has systematically wooed the OBCs, marginalised communities like the Matuas and tribal groups,” says Narayan, whose latest book, Republic of Hindutva, talks about the RSS and how it helps the BJP in electoral politics.

ALSO READ: Mughal, Miya And Oxomiya

According to him, the BJP uses the icons and gods of these marginalised communities and drafts them into its larger Hindutva politics. PM Modi even visited the main Matua temple in Orakandi during his recent visit to Bangladesh. He started his 2019 Bengal campaign by seeking the blessings of the late Boro Maa Binapani Devi, head of the Matua sect. The Matuas are one of the largest Dalit communities of West Bengal, who migrated from East Bengal across the decades that span what is called the ‘long Partition’.

The role of the RSS is crucial in all this, since they work close to the ground and are aware of the changes that take place in society. That’s especially true in a state like West Bengal. “It is their feedback that helps the BJP decide which caste or community to work on,” Narayan explains. He says the TMC too needs polarisation to ensure it gets the 30 per cent Muslim vote. However, it’s a risky tactic. “The counter-mobilisation will only help the BJP,” he explains.

ALSO READ: Shifting The Poles

In Assam, the game is more complex. The BJP has tried to go beyond the strong Assamese sense of identity to awaken the larger Hindu consciousness by invoking the Bhakti movement. Several BJP leaders, including Amit Shah and UP CM Yogi Adityanath, another star campaigner, have talked about “reviving the Bhakti movement”. They evoke the name of Srimanta Sankardev, the 15th-16th-century saint and poet who is considered a symbol of Assamese culture, but is also a key Vaishnavite figure, and hence compatible with the BJP’s political worldview.

Prodyut Bora, one of the founders of the BJP’s IT Cell, believes polarisation remains the bedrock of the party’s political strategy. He quit the BJP in 2015 and founded the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in Assam. But he too cites the “number of Muslims” in Assam—that’s part of a historical debate around which politics in the northeastern state has revolved for decades. Except, there’s a nuance. The BJP’s politics only partly matches with what the Assamese feel—the latter have stronger feelings about “outsiders”, and this is not restricted to Muslims. Bora, however, cites numbers—likely 36-37 per cent of the population, as the 2021 census may reveal, he says. “The reality cannot be wished away.” The BJP had got only 30 per cent of the total votes polled in 2016, but it managed to win because the opposition was divided. “They have managed to keep the opposition splintered this time too. Though the Congress and AIUDF will consolidate Muslim votes, it may not be enough for an outright victory,” Bora adds.

The BJP under Modi-Shah has never made a play for Muslim votes; party leaders believe it’s futile trying to woo them, so their strategy has always been to fortify the other side. But in a state like Kerala, which has a 27 per cent Muslim population, that has been a deterrent. The BJP’s inability to make much headway in the state relates not only to that, however. Kerala is a complex place, with a political culture that has strong elements antithetical to saffron. That has not stopped them from trying. Kerala’s substantial Christian population, about 18 per cent, has added a new dimension to its polarisation strategies—the party has been reaching out to sections among the Christians. The Jacobites, currently engaged in a sibling feud with the Syrian Orthodox church, are naturally part of the gambit.

“When PM Modi made a reference to Judas betraying Jesus Christ, it was not a random reference. It was a well-thought-out analogy meant to appeal to the Christians,” explains a senior BJP leader. He admits his party is a long way off from making any electoral gains in Kerala, though an increase in voteshare is very likely. “It’s a bastion that’s going to take some time, but can definitely be breached. Did anyone think the BJP will emerge as the main challenger to the TMC and come so close to winning West Bengal?” he asks.

Sanjay Kumar, director, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), also says the BJP has not limited itself to the Hindu-Muslim binary. He doesn’t rule out the possibility of that strand emerging as the long-drawn elections for Bengal carry on. “The first four phases are not likely to see any polarisation on communal lines. It is after that, if the BJP thinks it is not winning, that Hindu-Muslim polarisation will start. There are a sizeable number of Muslim voters in the last four phases and attempts to polarise may be made then,” he tells Outlook. As of now, the BJP is largely banking on anti-incumbency sentiments against Mamata Banerjee’s 10-year rule, and the issues of corruption and violence. “The party will resort to polarisation if it’s not confident of winning, like what happened in Bihar polls during the third phase,” Kumar says.

Regarding Tamil Nadu, he says, the BJP is shrewd enough to know it has to maintain a low profile and allow partner AIADMK to take the lead. “The BJP cannot campaign on the Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan plank in the southern state. That’s alien to Tamil Nadu voters,” he adds. The BJP is not the only national party that finds itself a lesser entity in this state. The Congress too is playing junior partner to ally DMK, getting to fight only on 25 of the 234 seats. But all of this may be a transitional affair. Narayan feels the opposition space is shrinking fast, and unless the Congress and other parties have an effective counter-strategy, the BJP will succeed in expanding its footprints across the country. And a core reason is the way its political vocabulary—sharpening the sometimes deep mutual social animus that exists in Indian society—is actually altering politics everywhere.