Very few national heroes have resonance beyond their national boundary and that too for long. The intense scrutiny of history reduces them to mere statues that millions of their countrymen walk past every day. In a country with a pathological penchant for hero worship, it is surprising that the first prime minister of India, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, has to struggle to remain relevant. Ironically, the resolve of the Narendra Modi government to observe the 125th birth anniversary of Nehru with fanfare has compelled the Congress to dust him out of their history shelf.

K.M. Munshi, in his book The Ruin That Britain Wrought (published in 1946), summarises Britain’s India policy thus: “...to impose on an ancient and highly complex culture and society which the Britishers considered inferior, the outward semblances of a crude European culture and second, to concentrate all political power in the hands of the governing corporation, the civil service”.

Nehru’s own generation saw him as a deviationist and a visionary at the same time, for almost the same reasons.

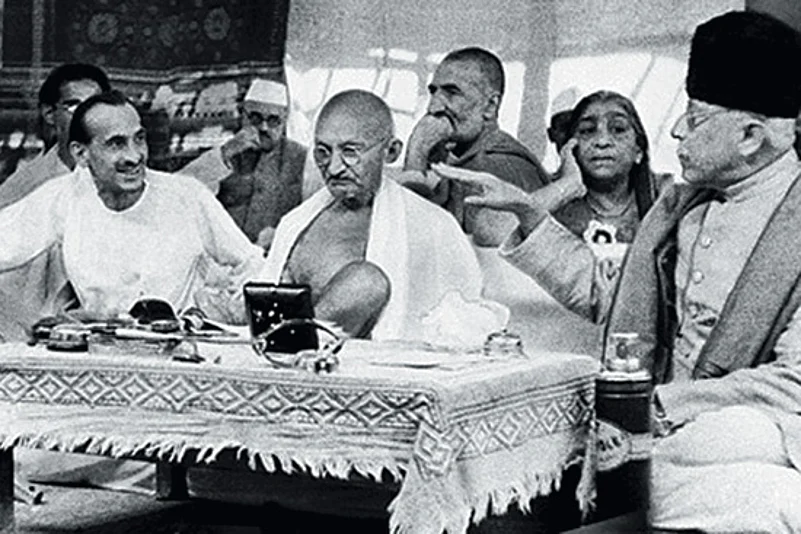

Mahatma Gandhi’s letters to Nehru on governance speaks volumes on Gandhi’s emphasis on Hind Swaraj, rural economy and the cultural component in governance. He and Nehru had diametrically opposite views on the economy. Gandhi advocated an agro-based, rural-oriented economy to cover eighty-five per cent of the population when the colonial power left. Nehru seemed to have contempt for rural folks “mired in self-inflicted poverty and superstition”. While the Mahatma’s model, later followed up by JP, Acharya Vinoba Bhave and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, was a reversal of ‘Britain’s India policy’, Nehru wanted the neo-Indian model to be a synthesis, the British soul in Indian body.

Nehru wanted Independent India to be founded on the principles of non-alignment, Panchsheel and the Gandhian idea of peace and non-violence, as opposed to a new and emerging post-colonial world-order which was looking to a newer economic paradigm different from Marxism. Soviet writers like Modeste Rubinstein and Ulyanovsky were impressed by the ‘scientific and socialist outlook of Nehru’ and hoped for a socialist India. But many among the Indian communist movement saw him as the progeny of western liberalism.

Shortly before independence, none other than Gandhi himself made a prophetic remark when he wrote to Nehru: “You have no uncertainty about the science of socialism but you do not know in full how you will apply it when you have the power (Gandhi, Collected Works, vol.57, pp.30-31)”.

Nehru’s application of socialism resulted in a colossus of chaos, the burden of which the country carried for over half a century. His initiatives of planned economy, rapid industrialisation and refining political culture through parliamentary democracy rather than Gandhian panchayati raj, and his emphasis on the scientific temper through education were acclaimed as path-breaking. But his critics would still hold him responsible for continuing the British Raj through his political style (acquired during the freedom struggle), emphasis on western paradigms, preference of the government over party to reach out to people and ultra-centralism bordering on authoritarianism, as against federalism and collectivism.

The centre-state relationship, with its decisive tilt in favour of central authority, led to distortions in the functioning of the Constitution and concentration of power in the hands of the Centre, leading to inequalities in economic advancement, commented veteran Marxist leader B.T. Ranadive. (National Problems and the Role of the Working Class, Calcutta: 1989).

Nehru’s differences with Acharya J.B. Kripalani reached a crisis when the latter publicly disapproved of the government’s ‘timidity’ towards Pakistan, advocated an economic blockade of Kashmir, and demanded revocation of ‘standstill agreements’ with the Nizam. Such a strong disapproval of Nehru’s policy resulted in Kripalani’s resignation from the Congress presidency in November 1947. In a moving speech before AICC delegates, Kripalani underlined the ideological content of his stand against government’s supremacy over the party: “If there is no free and full cooperation between the governments and the Congress organisation, the result is misunderstanding and confusion such as prevalent today in the ranks of the Congress and in the minds of people. Nor can the Congress serve as a living and effective link between the government and the people unless the leadership in the government and in the Congress work in closest harmony. It is the party which is in constant touch with people in villages and towns and reflects changes in their will and temper. It is the party from which the government...derives its power. Any action which weakens the organisation of the party or lowers its prestige in the eyes of the people must sooner or later undermine the position of the government” (All India Congress Bulletin, 1947: No.6, pp.11-12).

Little wonder that later generations of Congressmen, non-Congress parties and the Left pitched their tents in the political arena as staunch anti-Nehruvians, though Nehru himself stood for nothing in particular, yet represented the collective confusion that pervaded the ideological space in the post-independence national polity.

Nehru carried his non-violence to the extent of suggesting that India needs no army, as we have no enemies. This, even after the bitter experience of the Pakistan-sponsored attack in Kashmir. His blind trust in the then Kashmiri leadership, leading to a virtual handing over of the state to one family, and his unshakable faith in the goodness of the Chinese leadership, leading to the conversion of the Indo-Tibet border to Indo-China border, are a few of the blunders that his critics use to silence his dutiful, albeit dwindling, worshippers.

As for the present, the new government at the Centre has silenced its critics effectively by observing the 125th birth anniversary of Jawaharlal Nehru. Very few iconic heroes have been able to sustain their reputation in the aftermath of reinterpretation. Nehru is no exception. A grateful nation may still find a hero in him, yet throw his party into the dustbin of history.

The struggle between India and Bharat within Nehru was never resolved. His legacy continues in the struggle for identity and in our unique narrative to this day in the India that is Bharat.

(Former editor of Organiser, Seshadri Chari is convenor of the BJP foreign policy cell)