The Indian Constitution is re-emerging today as a subject of study and an object of scrutiny. There is an emergent sea change in society’s understanding of the Constitution’s status. At a recent talk that I gave about the Preamble’s essential concepts (liberty, equality and dignity), a faculty member in the audience challenged my reverential attitude toward fundamental rights, asking, ‘What’s so sacred about the Constitution?’ This person was no leftist revolutionary; she was a Modi supporter.

While macro-economic challenges forced by global capitalism erode the viability of the democratic welfare-state, undermining the ideology of the welfare state would be a natural strategy for both global corporations and cash-strapped democratic states. When the architecture of the welfare state is inbuilt into the Constitution itself, undermining the ideology of aspects of the Constitution would be a necessary consequence of the strategy. For the past two decades, democratic governments have already sought to convince their people of the need to balance fundamental rights against perceived threats over ‘security’. The acceptance of state exigency as superior to constitutional basics gets hardened with the triumph of the security paradigm (in avatars like National Security Act, UAPA, sedition, etc) over liberty (freedom of expression, habeus corpus, due process of law), or the normalisation of invasive surveillance (with global corporations and nation-states in connivance) that tramples citizens’ privacy. This helps to catalyse atavism about the nature of state power: a return to the attitudes of many millennia back when we regarded it as the natural right of authorities to rule as they will (that is, not in line with contemporary principles of egalitarian justice). And in a certain sense, I think that behind the question that was posed to me on the sacredness of the Constitution was the question, ‘Why should our executive government be bound by egalitarian justice?’

A dizzying spate of new books on the Constitution by top publishers attests to this new environment, probing into the very nature of democratic constitutions and principles. Several studies have recently appeared: Tripurdaman Singh’s Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India (Penguin, 2020), Gautam Bhatia’s The Transformative Constitution: A Radical Biography in Nine Acts (Harper Collins, 2019), Chintan Chandrachud’s The Cases that India Forgot (Juggernaut, 2020), Madav Khosla’s India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy (Harvard University Press, 2019), and my own Ambedkar’s Preamble: A Secret History of the Constitution of India (Penguin, 2020). It is the first two books mentioned that I want to focus on here.

Tripurdaman Singh’s book is exceptionally quick-paced, reader-friendly, and well-written, excepting one dissonant chord repeatedly struck throughout the entire length of the book. That dissonant chord, or jarring needle-scratch, is the raging animus against Jawaharlal Nehru, the villain of Singh’s story. Singh portrays Nehru as “a dictator”, as the “authoritarian” who dismantled and permanently foreclosed liberal democracy in India, and much worse. The entire narrative around the First Amendment to the Constitution is constructed to establish Nehru’s brazen, egotistical effort to “have his own way”. So graphic is the character assassination of India’s first prime minister that the scenes focusing on him evoke the genre of revenge-porn, here enacted for the perverse titillation of the right-leaning libertarian gaze.

More dangerously, Singh’s book seems to play to the recent efforts to decouple state power from democratic principles of egalitarian justice, by showing how icons earlier revered for championing such principles (especially Nehru), were no different from any other executive seeking to augment their own power at any cost. Such a cynical narrative insidiously supports today’s waxing atavism.

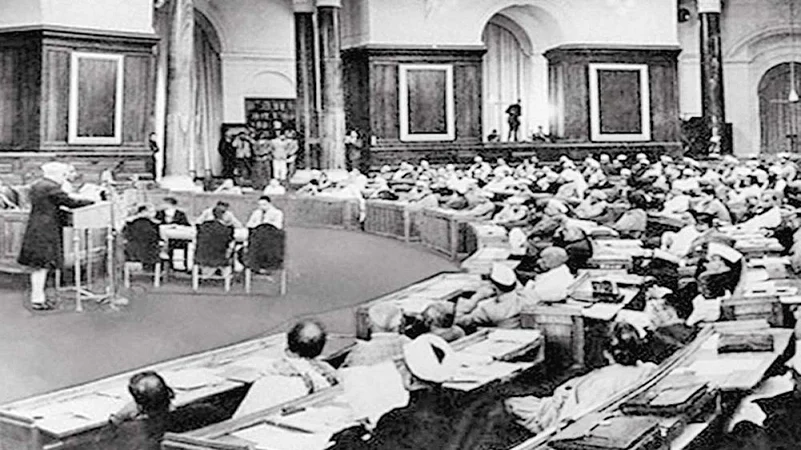

The book does have its merits, to be sure. It elegantly recounts the tumultuous events unfolding in 1950 and early 1951—primarily, the challenges government faced in pursuing its foreign policy (especially with Pakistan) and social justice policies of zamindari abolition and land reform, as well as reservation—as a result of constant excoriating negative press, and a string of judicial pronouncements against government with regard to freedom of expression, and the rights to private property and to equality. All of this led Nehru and his cabinet to draft the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill, which the beleaguered PM introduced into Parliament on May 12, 1951, pushing it through in the course of some four harrowing weeks—Singh does not make clear, precisely, which sixteen days among these are the eponymous stormy ones.

Also blurred in the book are the different motivations and interests of the several cabinet members who supported Nehru’s amendment; obviously, they did not all agree on every aspect—Ambedkar’s primary motivation, for example, arose from the court’s rejection of reservation (meant to undergird substantive equality in a highly inegalitarian society) on the grounds of abstract liberal equality. Singh collapses the varied motivations into a single reduction to being ‘hungry for a party ticket’. Throughout the book, only the intentions of Nehru and his party are subjected to scrutiny and doubt, and most uncharitably so. Meanwhile, all the critiques by The Times of India against Nehru and his government’s policies are taken as objective and unmotivated, despite the obvious risk that they themselves might have represented class and caste biases against socially progressive reforms (especially, though not exclusively, about reservation policy). Similarly, the author takes the rulings of the high and apex courts at face value, ignoring the parallel history of their own rival aim to establish and augment the judiciary’s sphere of influence in the emerging Republic.

In stark contrast, Gautam Bhatia’s dense but lively book could not be more at odds with that of Singh. Far from assuming some libertarian ideal for Indian constitutionalism, Bhatia argues that liberty in the Indian context cannot be conceived (as it was during the 18th century American or French precedents) as a vertical relation between subjugated citizens under an oppressive government. Instead, Bhatia argues that the founders of India’s Republic were aware that private, non-state “structures and institutions were often sources of domination and authoritarianism” that had to be tackled constitutionally.

Bhatia’s ‘transformative’ reading of the Constitution traces how liberty, equality, and fraternity have evolved substantively towards a regulative ideal of democratic, egalitarian freedom. The ideal remains unrealised, but it serves to motivate citizens, and hopefully to influence government behaviour, looking forward. Thus, unlike for Singh, Bhatia does not believe that Indian liberal democracy was dead on arrival. Rather, the constitutional essentials upon which our Republic was founded remain there ready to be reanimated.

It follows, then, that the arbitrary authoritarianism of executive power need not be taken as inevitable. Our pre-constitutional past does not have to be our constitutional future.

(Rathore is author of Ambedkar’s Preamble: A Secret History of the Constitution of India)