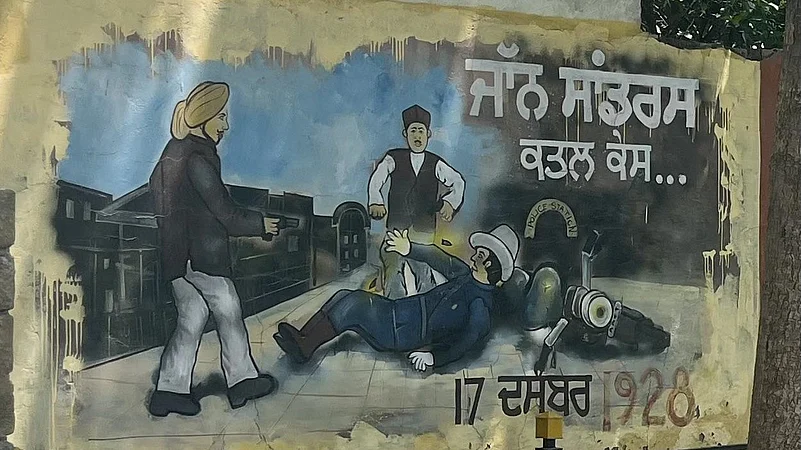

On the walls of the narrow streets that lead up to Khatkar Kalan, Shaheed Bhagat Singh's village, there are murals that stand out as incongruous. One depicts, in almost a cartoonish manner, Bhagat Singh's bullet flying directly into John Saunders' face—the British police officer assassinated on December 17, 1928. There is Shivram Rajguru running towards the scene, in his typical cap and a ghoulish expression. Bhagat Singh himself never wrote or talked too much about Saunders' killing and the aesthetics of this mural would have appalled him.

This mural may be painted by the over-zealous villagers. But the official side of Khatkar Kalan, with its Royal Palms and manicured grass, is no better. It's more like a picnic spot than a homage to a revolutionary. Under these palms, there is a family of five posing for selfies, the father adjusting his turban while his teenage daughter finds the perfect angle. "Bhagat Singh ji de ghar" (at Bhagat Singh's house), though they are actually standing in what the locals call a "sanitized park"—four times larger than Singh's actual ancestral home.

The first thing that strikes visitors about Khatkar Kalan isn't the revolutionary history—it's the Royal Palm trees (Roystonea regia) imported from the Caribbean. These towering non-natives stand guard over manicured lawns of American grass, creating an oddly tropical aesthetic in rural Punjab. The memorial feels like entering a theme park of revolution, but the most jarring contrast appears at the edge of this sanitized paradise where a concrete wall separates the pristine memorial from the reality beyond: cow dung cakes drying in the sun, makeshift huts, and waste dumps.

The imagery couldn't be more literal—revolutionary memory has been literally walled off from revolutionary reality. This isn't just poor urban planning. It's a perfect encapsulation of how contemporary India consumes its heroes: as Instagram-friendly experiences divorced from their actual context, their uncomfortable truths quarantined behind walls both literal and metaphorical.

The Violence We're Comfortable With

What makes the village's unofficial commemorations particularly fascinating are the raw, unfiltered murals that villagers have created themselves. These graphic depictions of violence would make any government curator uncomfortable. Beyond the cartoonish Saunders assassination, other murals throughout the narrow streets show revolutionary acts with an unflinching directness that official spaces would never dare display.

These aren't the sanitized "freedom struggle" narratives of official museums. These are raw depictions of what revolution actually looked like: messy, violent, personal. The mural's Hindi text doesn't euphemize the Saunders killing as "martyrdom" or "sacrifice"—it calls it what it was: "John Saunders Murder Case, 17th December 1928."

Compare this to the state-of-the-art museum just outside the village, where revolution becomes packaged as a sensory experience. Air-conditioned black-box exhibits with immersive sounds and multilingual displays transform Singh's intellectual life into emotional consumption. The museum acknowledges that Singh wrote primarily in Urdu, then proceeds to marginalize Urdu materials in favour of Hindi, Punjabi, and English displays. Even in death, Singh's linguistic identity gets edited for political convenience

The Democracy of Devotion

Throughout Khatkar Kalan, ordinary villagers have claimed Singh's memory in ways that official curators never could. Private houses feature personal monuments—not just of Singh, but of other revolutionaries like Udham Singh, whose statue stands atop one double-story house. There's something beautifully democratic about this approach: every family gets to choose their revolutionary hero, their version of resistance.

One house features tile-work of Guru Nanak's photograph—noteworthy because image worship isn't traditional in Sikhism, suggesting these visual displays carry identitarian weight beyond religious practice. Another wall displays a mural of Singh flanked by his parents, with carefully inscribed titles: "Father S. Kishan Singh", "Shaheed-e-Aazam S. Bhagat Singh", "Mother of Punjab, Mata Vidyavati Ji".

These aren't government-sanctioned narratives. They represent personal relationships with revolutionary memory, messy and immediate in ways that official commemoration can never be.

The Locked Doors of Memory

The most telling space in Khatkar Kalan is the Shaheed-e-Azam Sardar Bhagat Singh Memorial Library—a nearly 20-year-old building that contains no books. Its locked doors reveal empty shelves through glass windows, a sight that suggests this isn't neglect but policy. The village wants the appearance of honoring intellectual legacy while systematically avoiding engagement with actual ideas.

The irony is devastating: in a village dotted with graphic murals of revolutionary violence, the one space dedicated to revolutionary thought remains empty. There's comfort with Singh's bullets but terror of his books, ease with his martyrdom but fear of his socialism. Even Singh's ancestral house reflects the pattern. The ground floor has been converted into a museum with glass partitions separating viewers from recreated rooms, while the first floor remains locked to visitors. The design allows people to look but not touch, observe but not inhabit, consume but not engage.

The Revolution Will Not Be Air-Conditioned

Today's Khatkar Kalan presents a man who wrote "I am a revolutionary madman who is free even in a prison" ("ਮੈਂਇੱਕ ਐਸਾ ਇਨਕਲਾਬੀ ਪਾਗਲ ਹਾਂ ਜੋਜੇਲ ਵਿ ੱਚ ਵੀ ਅਜ਼ਾਦ ਹੈ") as a tourist destination where revolution becomes the brand but never the practice. The villagers' unfiltered murals suggest a hunger for authentic revolutionary memory that official spaces can't satisfy.

But even these grassroots commemorations focus more on Singh's actions than his ideas, his martyrdom than his vision for what should come after the violence. Perhaps that's the real tragedy of modern Khatkar Kalan: it hasn't forgotten Singh, but remembers him exactly how power wants—as a symbol to be consumed rather than an example to be followed. The palm trees continue growing, the selfies keep coming, and the library stands perpetually empty.

On Singh's 118th birth anniversary, his greatest victory isn't that he's remembered—it's that despite decades of sanitization, somewhere in those raw village murals, his uncomfortable questions still refuse to die.

(Gauri Malhotra is a final-year undergraduate student at Ashoka University)