The toy train between Kalka and Shimla, symbolic of a summer vacation in the hills for many North Indians, won’t run for a while now. The spindly narrow-gauge tracks, along the UNESCO-declared world heritage railway line, over which the train has rumbled for more than a century, traversing 96.6 kms delicately gliding past deodar forests, over chasms, through countless tunnels and what was once a stunningly cosy countryside before chugging into Shimla, have come undone in at least five places along the route.

The damaged rail tracks bear the scars of recent relentless rains, sudden, but devastating landslides, and decades of unchecked human greed that appear to have transformed the Queen of Hill Stations to the Crone of the Himalayas. This year, the spirit of Independence Day in the hill city was drowned by the crash and rumble of a hastily cast civilisation coming undone, leaving behind mounds of rubble and homes sucked into sludge.

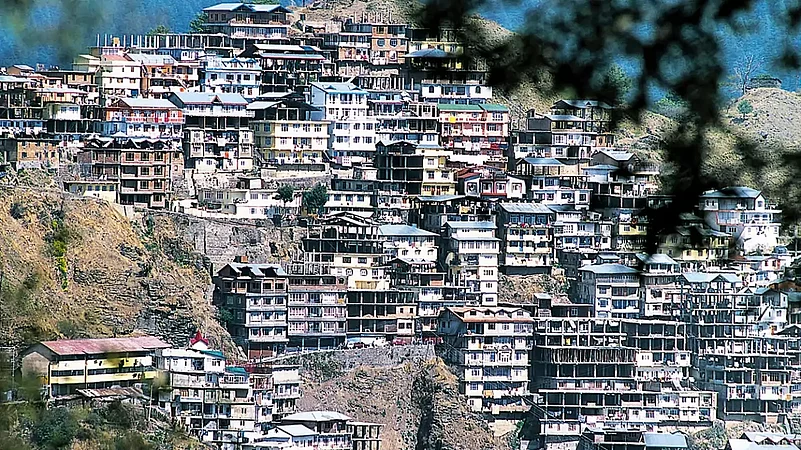

Between August 13 to 16, several high-rise buildings collapsed like a pack of flaky cards, roads cracked, opening up wide gashes in the development spiel of successive governments, as rubble, mud, stones and even the mighty deodars—large coniferous trees symbolic of the terrain—rolled down its slopes. Deodars are known for their deep root systems which have stabilised Shimla’s hillsides for decades.

Raaja Bhasin, a well-known Shimla historian, is passionate about the living legacy of Shimla. “Shimla speaks as much of the heritage of India as any other Indian town. It was built by Indian hands, paid for by Indian money and stands squarely on Indian soil,” he says.

But have the indigenous hands of subsequent generations also contributed towards pushing Shimla, inch by inch, towards the precipice of over-development?

“Unabated anthropogenic interventions, by way of buildings completely unsuited to the topography and altitude, relentless disturbance to fragile soil coupled with disregard for structural safety and the local environment had increased the hazard risks. Further, the infrastructure construction in Shimla, which was based on the presumption that nothing will go wrong, aggravated problems. It’s all a man-made disaster,” says V K Paul, Professor at School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi.

Laden with colonial legacy, pleasant weather and nurtured by the Himalayas, Shimla had flourished during the British regime and developed as an aspirational hill town post-1971. But its magical lure appeared to be its own enemy, attracting unabated and haphazard construction activity since Himachal Pradesh was conferred statehood in 1971, with Shimla as its capital.

Over the past 44 years, since the introduction of the Interim Shimla Development Plan (ISDP) in 1979, construction in Shimla proceeded with minimal adherence to safety standards. Until 2022, successive governments failed to finalise the Shimla Development Plan, conveniently ignoring violations and favouring extensive construction and development projects to gain electoral support.

Only Shanta Kumar from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) displayed the political determination to enforce the Town and Country Planning Act of 1977 to regulate illegal construction in Shimla. Himachal Pradesh’s sole municipal corporation governs the city. Urban and town planning in the state was virtually absent until the passage of this Act in 1977.

The state government introduced a ‘retention policy’ six times between 1994 and 2014 to legalise illegal constructions, often timed for election cycles. Currently, there are nearly 25,000 unauthorised structures in the state, half of them in Shimla. The latest attempt by Virbhadra Singh’s Congress-led government to regularise these before the 2017 elections was blocked by the HP High Court.

With administrative checks and balances virtually non-existent and greed fuelled by the combination of an expanding tourism circuit, a resurgence in the popular appeal of pilgrimage sites and unplanned infrastructure development, the apocalypse came visiting the hill slopes in and around Shimla this year.

Nearly 45 people paid with their lives for decades of chaotic, unscientific development. Twenty people died in a single tragic landslide near the ancient Shiv Bawadi temple in Shimla’s Summerhill area. Seven of t hose who died spanned across three generations of a single family!

Experts attribute Shimla’s devastation to rampant, unplanned construction, disregarding repeated alerts about its high susceptibility to landslides, seismic vulnerability, overpopulation exceeding its capacity and ecological instability. This has led to Shimla shedding its greenery, vacant spaces, iconic tennis courts, vertical slopes and nullahs, to now sport multistorey complexes, flats and commercial properties, including hotels and homestays, whose count never appears to halt.

The cosy hill station whose native population is around 2.75 lakh, hosted nearly 72 lakh tourists from January to May this year.

According to Dr Chetan Singh, former director of the Shimla-based Indian Institute of Advanced Study, the state capital’s boom coincided with rapid growth of urbanisation in other Indian towns. “Shimla is similar to the rest of towns in India. It is hardly a surprise, rather quite an anticipated one, due to the rise in population and merger of new areas in its urban limits. Unfortunately, no systematic plans were made to tackle the inevitable problem of uncontrolled constructions,” he says.

Dr Singh’s academic perspective mirrors questions raised by Suresh Bhardwaj, former Shimla MLA and ex-state minister for Urban Development, about the rampant illegal constructions and questionable relaxations in land-use norms.

“Why did past governments, mainly Congress, not complete the Shimla Development Plan (SDP), which I finished in 2022? It seems there was an agenda favouring influential figures, including politicians and hoteliers. I’ve raised these concerns in the state assembly, pointing out violations, some near the late Virbhadra Singh’s residence in the green belt. Norms were temporarily relaxed for approvals, then reinstated,” Bhardwaj says.

The journey of ‘development’ of Shimla started in 1971 when the state was granted full statehood, immortalised by then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s excursion in an open jeep with iconic state Congress leader Dr Y S Parmar, who braved heavy snowfall to make a formal announcement making Himachal Pradesh a full-fledged state.

The new state required bureaucrats and labour to support its growth. This brought an influx of government offices and migrants to Shimla. Employees moved from villages for improved education and healthcare, building homes. Each new house and locality became a hub for extended families seeking a better life. But as the population swelled, basic infrastructure could not keep pace with the increased footfalls in Shimla, including the upkeep of the town’s drainage network.

A 1992-93 government report recommended revitalising Shimla’s natural drainage, improving sewage systems, banning construction digging, decongesting by relocating institutions, and halting tree felling. But the report was ignored and Shimla kept growing developmentally obese, with its parts now crumbling under its own weight.

Now, besides the usual suspects, newer factors such as obstructed water flow, saturated soil due to record-breaking rains this year, compromised building designs, and rampant hill cutting have worsened the city’s problems.

“Today, the town’s very existence is at risk. We have collectively failed. I don’t want to be an alarmist, yet, there may be more such disasters in the making, if the problems are not fixed” says N K Negi, former chief architect of the Himachal Pradesh Public Works Department.

If life gives you lemons, make lemonade. But another peculiar cause for Shimla’s ‘Royal Delicious’ conundrum has also been its abundant harvest of apples, the most popular of which is the Royal Delicious variety.

The booming apple economy around Shimla has enabled apple farmers living on the outskirts of town to build houses, bungalows and buy land in Shimla. The apple boom increased illegal construction in Shimla’s Dhalli and Cemetery areas. Locals say Upper Shimla residents flouted norms and safety standards while building ambitious mansions. Open spaces are rare, to the point that funeral processions navigate interconnected roofs between buildings to reach a road.

“This (result of the booming apple economy) was one of the first reported instances of Shimla witnessing monstrous constructions. Nobody ever has dared to question the violators. Thereafter, the riches from apple farming were invested in such properties, in both multistorey houses and commercial constructions in Shimla,” recalls Prakash Lohumi, a veteran Shimla journalist. According to Lohumi, after Punjab government offices moved out of Shimla in 1966-67, many Himachal Pradesh government employees purchased palatial properties in town.

Any surplus funds they received as arrears from revised pay scales, mirroring Punjab’s, were invested in real estate. Subsequently, they sold these properties at substantial profits, leading to a surge in construction activity.

Tourism flourished in the hill station only post-1980s, when the Shimla-Kalka National Highway was widened as a two-lane road to improve mobility to the state capital. Also, tourism in the initial years, recalls Dr Singh, was expensive and only the relatively wealthy could travel and stay in Shimla. Gradually, as transportation grew and some cheaper hotels came up, tourism expanded.

Umesh Akre owns one of Shimla’s first hotels— Hotel Himland near St Edwards’ school—which he claims was the first earthquake-proof private building in town. “We, a group of few pioneering hoteliers, made a lot of effort then to hard-sell the state’s tourism potential, along with Shimla. It worked wonders,” he says.

Hotel Himland, along with others like Hotel Marina, Hotel Continental, Grand Hotel and Thakur Hotel were tourist beacons in Shimla, where hospitality biggies like Oberoi Cecil and Oberoi Clarkes already had a presence. But too much snow has melted off the Himalayan peaks below which Shimla is nestled since the first cluster of hotels sprung up.

The same hotel industry which gave tourism its wings in the Himalayan region has become a victim of the crisis this year, with the string of calamities driving down tourist footfalls to between zero to five percent since July this year, compared to the corresponding period in 2022.

Shimla, like many other Himachal towns, faces a unique challenge due to its location in a geologically unstable and environmentally sensitive region. Environmentalists stress that events in the Himalayas have a profound impact on the lives of millions in the downstream Indo-Gangetic plains.

Till last week, Himachal Pradesh has reported 400 deaths due to rains, landslides, building collapses and cloud burst-related incidents, of which the highest number, 51, were reported in Shimla district alone since June 24. The calamities have cost the state government Rs 8,663 crore in losses.

After the latest tragedy, Chief Minister Sukhwinder Singh Sukhu set up a committee of experts under S S Randhawa, Principal Scientist at HP State Council for Science, Technology and Environment, to study factors resulting in landslides, uprooting of hundreds of trees, building collapses and cases of land subsidence. The committee has been tasked with making recommendations to regulate future construction activity, ensure structural safety and save the hill station from sliding downhill, mostly on account of its own sins of commission and omission. The government has also imposed a temporary ban on construction activity, hill cutting and felling of trees, albeit for two weeks. The measure, according to the state’s chief secretary Prabodh Saxena, “will ensure safety for human lives, habitations, infrastructure and to preserve the fragile ecological environment of the hill state.” The Himachal Pradesh government has also asked the Centre to declare the latest spell of disaster as a natural calamity on the lines of the Bhuj earthquake and the Kedarnath tragedy.

According to Dr Singh, however, the state’s planners need more academic grounding for any corrective mechanisms to take institutional root. “I am not sure that there is even a single School of Architecture and Planning in the state! Worse, it is unlikely that the state has made any serious efforts to train an adequate number of qualified experts in techniques necessary for planning and constructing in mountain regions,” he says.

Once a seasonal seat of power in British India, human idiocy and the sheer power of nature cornered by environmental decay, have nearly unseated Shimla from its perch as the ‘Queen of the Hills’. Its road to redemption is all uphill, along the unstable slope where the deodars once thrived.

(This appeared in the print as 'Distress in the Deodars')