In 2008, the then Chief Minister of Jharkhand Shibu Soren declined the permission to burn the effigy of Ravan reportedly saying that he is our “Kulguru and people in the region worship him.” The connection that senior JMM leader drew between the great king Ravan and the Chota Nagpur plateau is a common myth that is part of oral histories which consider this area as Lanka.

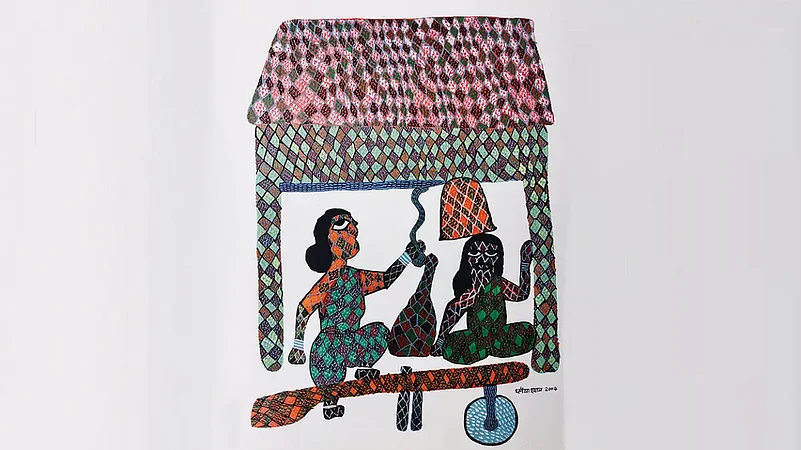

Reports cited by geologist Nitish Priyadarshi show that in the iron age when the great epic Ramayana was perceivably situated, there was Asura community surrounded by two Adivasi communities depicted as ‘Vanaras’ and ‘Rakshasas’. Eminent historians Romila Thapar and Majid Hayat Siddiqi have also pointed out that Mundas, considered to be the earliest settlers in this region, believe Asuras, an iron-smelting community, lived there before them. The abundance of gold in the banks of the Subarnarekha River also makes people connect Ravan’s gold palace in Lanka with this land. These myriad and scattered oral references to Ravan across the region while make ‘Dasamukha’, a common name given to Ravan, a worshipped character, the parallel grand celebrations of Ram Navami and Dussera in Jharkhand make it a more complex field of study. How can the land of Ravan celebrate Lord Rama? How the Adivasis who claim to have an ancestral connection with the king of Asuras relate to this grandeur? Is it just politicisation of Ram that is reflected in the mostly masculine celebration of the ‘Purushottam’ or there lies evidence of Adivasi adaptations celebrating Ram too? What is the position of Sita, considered an Adivasi?

ALSO READ: Who Is Ram And What Is His Story?

A look at the sacred geography of Jharkhand, a patient hearing to the adapted versions of the Ramayana in Mundari, Birhor and Santhal languages, and a dive into the politics of its overwhelming spread take us to the hilly terrains of orality, where once perhaps Ravan used to worship Lord Shiva. Kunal Shahdeo, a scholar at IIT-Bombay, who works on Hinduisation of Adivasis in Jharkhand, says, “If we look at the sacred geography of Jharkhand, we would find Shaivite, Shakti and Vaisnavite shrines and Deoris (small temples) spread across Jharkhand. Hence, some forms of what we today call Hinduism have been present in Jharkhand since the ages. Also, a large population of Hindus locally called Sadans, settled in Jharkhand in precolonial era, brought with them Hindu practices of the plains. The socio-cultural interactions between Sadans and Adivasis led to the spread of popular Hinduism among Adivasis.” Notably, the myths floated in oral histories related to the Ramayana in this region mostly connect it to the presence of Shiva. It reflects what Shahdeo attributes to the prevalence of Shaivite culture. However, the available Ram Kathas in different Austro-Asiatic languages depict different stories of omissions and adoptions. Belgian Jesuit scholar Camille Bulcke in his thesis titled “Ramkatha ki Utpatti Aur Vikas (The Genesis and Development of Ramkatha)” presented snippets of different Ramayana(s) available across Mundari, Birhor or Santhali languages. Popular Hindi writer and IAS officer Ranendra Kumar while speaking to Outlook says, “Sarat Chandra Roy in 1924 wrote a book on Birhor community. Current population of Birhors across Jharkhand is not more than 11–12,000. So, what would have been their population during the 1920s when Roy conducted the interviews could be anyone’s guess. Even then the reference to Ram, Sita and Lakhsman came several times.” It shows, as Kumar notes, the deep-rooted existence of the Ramayan in this region. Referring to Bulcke’s snippets of Santhali Ramayan, Kumar adds, “In Santhali tradition of the Ramayana we find that Ram stayed among Santhals during his return journey from the war. He founded a Shiv Mandir there and worshipped along with Sita.” Interestingly, in Birhor Ramayan, the glorification of Ram is not that vivid. According to Kumar, “Sita, in Birhor Ramayan is a daughter of an ailing mother. Once, Sita playfully broke the bow of Lord Shiva forcing Janak to decide that a person with that much strength could only be her competent partner. In Birhor Ramayan, Ravan was given such a dignified place where he could be killed only by a person with the power of 12 years’ uninterrupted meditation. Interestingly, in this Ramayan, Laxman killed Ravan, not Ram.”

ALSO READ: Who Is Ram? Defining The Enigma

The connection of the land with Sita is, however, much deep rooted than any other character. In his book, Adivasi Astitwa aur Jharkhandi Ashmita ke Sawal, the great scholar of language Ram Dayal Munda noted that the word ‘Sita’ could not be found in Sanskrit origin language. But in all of the Austro-Asiatic language like Mundari, Santhali, Birhori and Ho the word finds its place. In these languages Sita means ploughing. Kumar while focusing on the significance of Sita in the Adivasi culture says, “It was a matriarchal society where Janak metaphorically represented the Aryans who were mostly hunter-gatherers and were willing to learn cultivation. Sita was probably an agricultural expert whom Janak took away from Adivasis as a daughter, precisely to learn the nuances of the field.” The celebration of Sita as the feminist icon can also be found in the words of Ramachandra Gandhi. In his book Sita’s Kitchen, he mentioned how Sita is worshipped by different Adivasis as the provider of food and shelter. These celebrations of Sita and sometimes Ravan are what make these Ramayana(s) in this region different from the mainstream narratives. However, whether these different dimensions, as claimed by Kumar, have been prevalent among Adivasis for centuries or not is a matter of further enquiry.

However, Adivasi activist and scholar Ashwin Kumar Pankaj provides a different interpretation that questions the perennial existence of the Ramayana in the region. Notwithstanding what Ranendra Kumar says, Pankaj comes heavily on the propagation and penetration of the Ramayana in the region. Briefing on how historically the Ramayana had been pushed into this region, he states, “We are a Hindu civilization. During 12th century when rulers of different faiths came from outside, several mythologies were created to save Hindu religion until 17th–18th century. During colonial period when the British entered the scene, nationalist forces understood the necessity of including marginalized Dalits and Adivasi communities. Gandhi realized this very well that without their support the democratic reforms would be impossible.” Referring to the impact of the Ashram schools on the Adivasi population, the scholar points out, “During the 1930s, they started opening Ashram schools in the non-Hindu areas. Regular prayers, recitation of Ram Katha and the Bhagavad Gita, celebration of Navaratris were arranged. At this juncture, the nationalists recruited A.V. Thakkar, popularly known as the Thakkar Bapa, to weaken the social movements of Adivasis. They formed Adim Jati Seva Mandal, of which Rajendra Prasad later became president.” When Adivasi students passed out of these institutions in the 1950s and 1960s, says Pankaj, they were well aware of Ram Katha. “It penetrated in the last 200 years. It is simply the cultural politics,” he adds.

Whatever position scholars of various convictions may take, the violence during Ram Navami celebrations in Ranchi in April this year, leaving one person dead and several injured, only shows the politics of Ram being played to divide people. Hemant Soren’s decision to assign Sarna dharma to Adivasis is a counter to such notions of Hinduised imaginations. On Sita’s relation with this land, he continues to say, “Ram is a superman and Adivasis do not believe in any superman. Sita is jungle ki beti (the daughter of the forest). Adivasis have always fought for their mother and motherland. The Adivasi Ramayan speaks of revenge by Sita’s sons who reclaimed her position by defeating the outsider Ram, who abandoned their pregnant mother in the jungle.” This vibrant celebration of Sita does not comply with the superpower Lord Rama is attributed.

Spontaneously reproduced versions and multivalent interpretations of a great epic though enrich the culture, any forcible propagation and penetration decimates its essence. Ramanujan’s Three Hundred Ramayanas shows how literature transcends the binaries of Ram and Ravan. Any epic must be transgressive—celebration lies in the subversion, not in the compliance.

(This appeared in the print edition as "In the Abode of Sita")