Perhaps no other season wears a dichotomy on its sleeve as winter does. The stark, rough winter is no match to the warmth of the people sitting closely by the hearth or a fireplace. In this fireplace, sitting by the fire, stories are passed from generation to generation. Grandmothers share stories of pains and joys to their grandchildren. An inheritance of stories. For me, sitting by a fireplace brings back memories from the past. The memories of December 6, 1992, come alive. This winter, the memories are more vivid, perhaps more hurtful.

That day …

It was the evening of December 6. I was sitting by the fire lit with the help of haystack and rice bran in the middle of the courtyard. By my side, on a jute sack stretched on the ground, was sitting my one-year-old cousin sister. It was not past 7 pm, but in the village with no electricity, it was almost dinner time. The dinner was being prepared. I had just finished my Sahajpath lesson and faintly remember that I was waiting for dinner to be served.

The nascent darkness of that night was being occasionally blown into smithereens by the fire. The dust from the fire sparkled like broken stars before melting into darkness in the womb of night that evening. I had a small piece of wood or dry stem of bamboo in my hand to prick the fire inside when the upper layer of the fire was turning into lifeless cold ashes. With the dry piece of bamboo, I was occasionally crisscrossing lines of various shapes on the ground.

On the eastern side of the courtyard, the mango tree was dizzying in the cold. Behind the mango tree, the piled haystack of the Kharif paddies was placed—the top of the crop resembled minarets of a mosque. Suddenly, the brooding night in the bosom of the winter ruptured with the sound of the big stone thrown over our house. The stone landed on the sack on which my sister was sitting, missing her head by inches.

On the eastern side of the courtyard, the mango tree was dizzying in the cold. Behind the mango tree, the piled haystack of the Kharif paddies was placed—the top of the crop resembled minarets of a mosque. Suddenly, the brooding night in the bosom of the winter ruptured with the sound of the big stone thrown over our house. The stone landed on the sack on which my sister was sitting, missing her head by inches.

My aunt shouted that it must be the work of some wanton boys. I remember running back into my room. One stone followed another, then another. Then, the next few days, it was a regular nocturnal phenomenon in the area we lived in.

The neighbours and party cadres began to guard our houses. In my family, people were discussing something in a hushed tone. The little me could sense their fear, numbness and sheer helplessness. I have forgotten most of the discussions, but the word that stayed with me is Babri demolition

After a few days, things got a semblance of normalcy. The people who came to stand with us outnumbered the chants that followed the stones on those harrowing nights. We moved on. I moved on, but I can still hear the thud of the stone thrown that night every day since then, particularly during elections.

The Circle:

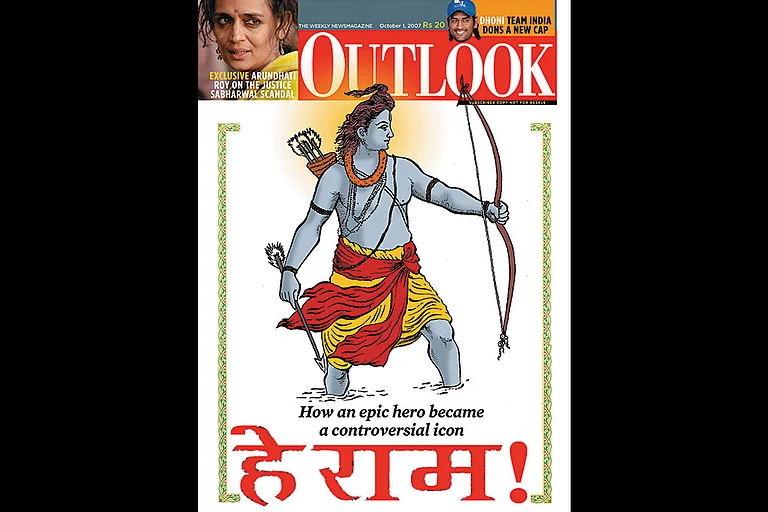

It's 2024. Thirty-two years have gone by. From Muzaffarnagar to Godhra to the Delhi riots, the country has seen it all. People have seen and heard Yeti Narashimhanand and Kapil Mishra as well as Gauri Lankesh, and Naresh Dabholkar. The country has seen old women protesting the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Those stones thrown at our houses that night are celebrating January 22 as a victory—the victory of the majority, as it's being portrayed in many media, over the victory of the minority.

The nation which lost and bled much in 1947 didn't succumb to the wounds of the partition because the majority of common people rejected hatred. Some of the leaders also believed in the idea of secularism. They didn't let our country fall apart.

But these 32 years never culminated in a horizontal line. Rather, it took the shape of a circle of hatred. From Jawaharlal Nehru's disapproval of Dr Rajendra Prasad's presence at the inauguration ceremony of the Somnath temple, to the presiding of the Prime Minister in the consecration ceremony in Ayodhya on January 22, it has been a long journey of 32 years.

It's winter again. The thumping victory cries are in the air. This time, the media in every form is with them. Constitutional morality and ethos are smeared with dust. People from various walks of life, irrespective of caste, class and religion worship, have been invited. Will they attend the event with complete disregard for the emotions of the minorities? So, this winter is also going to be the death of the heroes? Has the stone completed its journey? Winter has its answer. What is next after this circle?

Winter knows how afraid I am. Winter knows how I am thinking of postponing my train journey on January 22. What will happen if anyone asks my name?

But winter also knows that fear is temporary. Amid all these celebrations, this Sankranti, too, Jogen Kaku, my neighbour, knocked on our door with a bagful of pithe. The Bura Buri Fair—a fair in the village on Makar Sankranti—was attended by all of us. This brings hope.

It's the common people who have kept the idea of India alive. The idea of India is bigger than the stones thrown that night.

Those stones came in stealthily, but those who protected us came openly. That kept the hope alive, but is the hope still alive?

The Muslims are discussing what to do on January 22—to stay put at home or to treat it like a normal day. We have many questions.

But hope is more contagious than hatred. So, the poet in me hopes that the barefooted devotees will ask for once, from their hearts—does God want his house to be built by the homeless people? Hope some devotees will ask this question and seek an answer from God in this bone-chilling winter.

Give me a God …

Gimme a God

I have seen you have many

You all are praying to them

And fighting, killing in their names.

I just want one

Who sprouts food in the barren land

and bleeds in my wound

Who won't need any rules

Will only comfort me

in my monthly pain.

Gimme a god

Who won't ask me for once

Straight - queer - gay or rainbow

She will embrace me for all.

Gimme a god

who doesn't have a home

and walk barefoot

and squat on the sand.

Gimme a god

who doesn't bandwidth sword

over the neighbour's head

and does not have a superiority complex.

No

I don't want your gods at all

keep them in their houses.

I want to walk with the

mad man wandering and singing

alone peaceful in a land

where god knows the taste of cold

and everyone has a home.