Strategic Retreat

It was girl power at its frightening best. For several wintry days, burqa-clad girls armed with lathis and, reportedly, Kalashnikovs, barricaded themselves in a children's library, chanting slogans that challenged President Pervez Musharraf to evict them from government property. They wouldn't emerge from the library until their demands were met, they declared-- the tone of finality, of non-negotiability, was underlined by their expressed willingness to die for their cause. It was at once a brazen defiance of authority, a religious war cry against the president's patented policy of enlightened moderation, and a provocative Islamist strategy of employing girls as footsoldiers in the battle against the establishment.

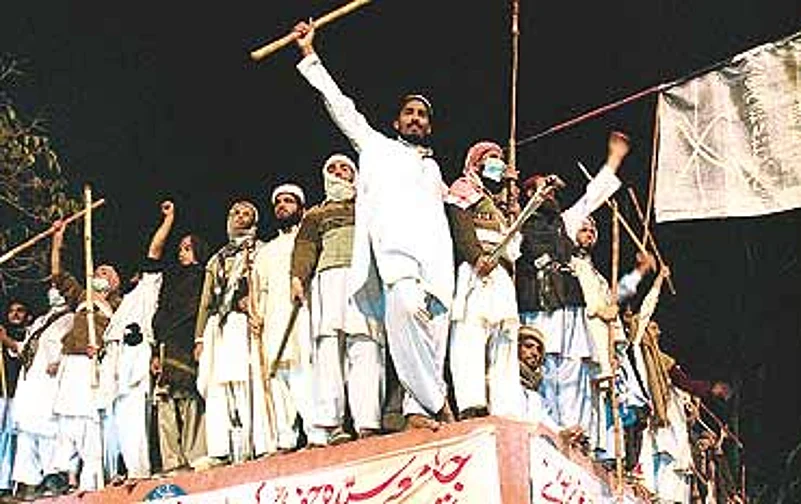

What provoked the girls from the seminary of Jamia Hafsa to storm the library was a notice the Capital Development Authority (CDA) issued to 81 mosques and madrassas in Islamabad, asking them to vacate illegal constructions that had been earmarked for demolition. Listed in these 81 mosques was the Lal Masjid complex in downtown Islamabad that houses the Jamia Hafsa seminary for boys, and sandwiched between these two, a public library called Modern Children's Library. Aware of the government's intent, apparent from the January 20 demolition of the Jamia Amir Hamza mosque to enable expansion of the Islamabad-Murree highway, furious Jamia Hafsa girls broke into the public library the following day. Their demand: no further demolition of mosques and reconstruction of the six that had been razed to the ground in the last two-and-a-half years. Boys from the adjacent seminary acted on cue-- brandishing weapons, including guns, they threw a ring around the library.

The choices before Musharraf in Awan-e-Sadr, or President's House, just a 10-minute drive from the Lal Masjid, was tough. If he ordered the eviction of the girls, the inevitable bloodbath would galvanise the anti-state Islamists in the crucial election year and strengthen the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), an umbrella group of religious parties. Were he to continue watching the siege helplessly, it would be tantamount to accepting that his writ did not run even in Islamabad, let alone the tribal areas; that he could be easily blackmailed into submission.

As truckloads of security personnel moved into the area and the nation waited with bated breath, a high-level meeting of officers, particularly those from the Pakistani air force, advised restraint. Mounting pressure on the government were people like Maulana Abdul Ghafoor Haideri, secretary-general, Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (Fazlur Rahman group), who openly spoke of violence if the girls' demands weren't met in full. "We can't give any assurance that protests would remain peaceful in the future," he said.

On the other side of the divide, newspapers wrote about the event's significance for Pakistan. Even the Lahore-based conservative daily, The Nation, said: "How does one humour fanatics and, more importantly, should one humour fanatics at all, are questions the government should ask itself. The government's conciliatory initiative would set a dangerous precedent, though it really does appear to be the only way to handle the problem at the moment."

Ultimately, the government caved in on February 12: minister for religious affairs Ejaz-ul Haq placed bricks at the site where the Amir Hamza mosque once stood, thus symbolically conveying the state's readiness to rebuild it. An 11-member committee has been formed to look afresh at the list of 81 mosques earmarked for demolition and the possibility of providing alternate land for their relocation.

As Haq laid the first bricks at the site and offered prayers, the Mohtamim (principal) of Jamia Hafsa, Ume Hassan, preened: "This is a result of the bravery shown by the girls... At most we would have been killed and embraced martyrdom." Hassan only conditionally opened the doors of the library. "We will continue to have administrative control over the library until the other six destroyed mosques are renovated. Notices to 81 other mosques in Islamabad have to be withdrawn also," she threatened. On February 13, the girls rechristened the library as the Modern Islamic Children's Library.

During the siege, the girls admitted a few visitors in the library. One of them was academician Farhat Taj. She was made to promise that she would kill the editor of the Danish newspaper that ran the offensive cartoons against Prophet Mohammed in 2005. "The girls questioned my personal appearance--my hairdo and my attire, which in their view was 'too tight' and therefore un-Islamic. They told me I was committing a 'sin' by roaming all over the world unaccompanied by my male relations and sans the burqa," writes Taj. Musharraf's enlightened moderation doesn't seem to have penetrated the seminary--Taj says the girls are not allowed to play games, go on outdoor trips or watch TV. "Watching TV, they said, was banned in Islam. The students and teachers told me that the madrassa is grooming wives and mothers for jehadis, female suicide bombers and female footsoldiers who will clash with the law enforcement agencies of Pakistan, if necessary," observed Taj.

Many blame past governments of succumbing to religious blackmail and allowing mosques to be illegally built on public land. Disallowing places of worship to be constructed illegally is decidedly easier to tackle than bulldozing them to rubble, they say. That it had overlooked the road often taken by vvips also made it a security threat. For most citizens of Islamabad, apart from the Islamists that is, the demolition of mosques wasn't an issue. As analyst Gen (retd) Talat Masood told Outlook, "Most Pakistanis pray at home or wherever they are. They go to mosques only on Fridays and festivals. For these purposes, legally-constructed mosques in colonies where they live suffice."

The MMA, however, accuses the government of bias, saying it has regularised churches and Christians slums which encroach public land. Further, official statistics say only 273 of the thousands of mosques and seminaries in the country are officially registered. Does this mean the government is entitled to demolish the rest, ask MMA leaders.

But the siege, says analyst Dr Ayesha Siddiqa, symbolises "a serious threat to civil society and the country." "Years of using militancy as a policy tool and the free flow of small arms into the country has resulted in strengthening the militant groups," she goes on to add. "Renegade groups of different militant organisations are regrouping, which will further threaten the state and society." The siege drama, perhaps, is a chilling presage of what the future holds for Pakistan.