On a late Sunday night, from a home in upscale Lahore, comes the faint din of Bryan Adam's insufferable love. Unsurprisingly, there are young women inside ready to be misled, scattered around their men in a good ratio of one is to one, though at the moment it's not clear who has the rights on whom. The childhood friends who passed through the same high-end Lahore school and the lovers they collected outside the alumni are in a tight familiar group talking all at once and drinking.

A few hours ago, a bootlegger had come and delivered liquor here, a popular way of accessing it in a country where only minorities like Christians and diplomats are allowed to consume alcohol. The most common crime in this country is not conspiring to kill the kafirs but drinking. With the coming of General Musharraf's somewhat practical governance, those rare house sniffs by cops and the more common street checks to seek out drinkers for eventual fining, imprisonment or Islamic lashing have virtually been abolished. So, the drinking in this home goes on smoothly with no external pressure, a get-together like anywhere else, with stately boys-to-men types in smart clothes and girls who have freshly waxed their upper lips.

When a slender girl leans to fetch something from the table, her kids' section T-shirt slides up a little, revealing a fish tattoo on her almost white back. The fish is excellent art but it's also our first view of a bare back in over two weeks, if cricketers during net sessions are excluded. Modern girls in Pakistan's cities do walk the streets wearing what are called 'western' clothes but they are sadly not a regular sight. To find some pleasing economy of clothes and stiletto-tipped legs, acquaintance with a Pakistani is essential, because it's homes that become pubs, transient, but as loud, young and physical as in the rest of the world.

The get-together in this house, however, is only a dinner ritual. "This is not a party, we won't be dressed like this for a party," says a girl, pointing at her plain shirt. Standing beside her is a girl in perfectly tight jeans who introduces herself as "Zee Q" which is short for something long. She is one of Pakistan's top models. Fashion shows here are not very different from those in India but of shocking mini-skirts and swimsuits, she says, there are none on the ramp. There are these undying conservatives who oppose the shows but unlike in India, she says, "no fashion show has ever been disrupted."

Among the young men in such places who want to discuss world affairs, General Musharraf is very popular. They admire his battle against the mullahs. Some dream that he will bring about a day when the pub would come to Pakistan and replace restaurants that dress like bars. From outside, Gun Smoke looks exactly like a pub, declaring in huge fonts at the door, "It's Smokin..." because brilliant marketing men all over the world believe including 'g' after 'Smokin' will estrange the young. But Gun Smoke serves no liquor. As compensation, one can have unlimited groundnuts and throw the shells on the floor. The aisle is filled with such shells. And on the menu are such exotic offerings as "Ultimate Margarita", a non-alcoholic cocktail.

A few metres away, Cafe Zouk is what teenagers call "the happening place". In a corner is a counter with bar stools where short-sleeved hunks sit majestically and have Coca-Cola. But Zouk is so popular that on some days owner Ahmad Khokhar has to "lock the main door from inside to stop people from entering". On New Year's night, he converts the restaurant into a dance floor. "But it is all in private," he says. "Dancing is still not accepted by society."

Lahore and Karachi do not sleep, though it's not clear what keeps them awake. In public places, all that people can do is eat till early hours and strangely, they do that.Of all the unsleeping nooks in the cities, Lahore's Heera Mandi has the best excuse for staying up. It's an unlawful, indestructible red-light area in the shadow of a mosque that Aurangzeb built, a soft-lit world of painted women cluttered with men who are passing through. Named after Heera Singh, a friend of the 19th century Maharaja of Lahore, the market with its narrow winding lanes used to be culture itself. Even today, the nautch girls, the music and the restaurants remain. Only respectability has moved out.

On any given night here, especially closer to midnight, many strands of full-volume music fill the lanes. There are small open rooms where over 50 people sit and watch Indian cable television, all channels except Indian news being available here. In some rooms three TVs show three different channels with the audio of all three on. Impoverished men play pool and snooker with astonishing skill, the tables sometimes as small as a carrom board. Frantic betting goes on around the pool tables. A thin, delicate man on the road with flowers in his hands blocks a car's way. The driver is getting frustrated but finally he gives the man twenty rupees. The delicate man leaves in search of another car. Life goes on.

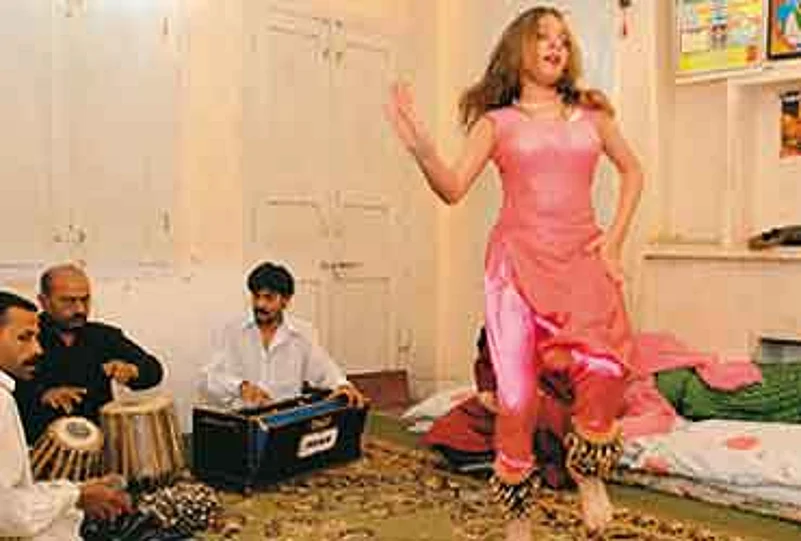

Small rooms at the foot of ancient buildings flank another narrow way. Inside these rooms with wide open doors, there are highly decorated girls on cheap sofas. These are the nautch girls. Once they were tradition, now they are only considered expensive prostitutes. When we enter, the musicians on the floor get up and quickly shut the doors. They begin to play their beaten instruments. The girl begins to dance atrociously, seldom meeting the eye but admiring herself in a mirror that's behind us. She is fully clothed while dancing and there is nothing sexual about her movements. Two thousand rupees for her dances. A local may have bargained for better.

In one corner of Heera Mandi is Cooco's Den, a restaurant run by an artist who says Pakistan has not accepted him because his muses are prostitutes. "I cannot help it. I come from that background." The women in his family were nautch girls. When he started the restaurant nine years ago in his old ancestral home, it failed, "because educated people didn't want to be seen in a red-light area". But all that has changed now. Most of the world's famous who land in Lahore visit Cooco's today. A few days ago, Jinnah's daughter Dina Wadia ate here. Urmila Matondkar has been here.

Cooco's terrace is filled with Lahore's upper class. A Pakistani with an American accent feeds his extended family while his young Chinese wife tolerates her mother-in-law. Hindi remix flows from large speakers. Chicken biryani here costs just Rs 95 but mutton chops are Rs 350. Plain rice with a boiled egg dropped in channa masala is Rs 110.

A few metres from Cooco's is a huge house with 20 rooms in which lives one man. Usually affluence and poverty are neatly segregated in Lahore but the mansion is a relic from the times when Heera Mandi used to be a good address. It's not clear if he will like the description, but Yusuf Salahuddin, a friendly rich man who has inherited the house, could be described as a socialite ("I have a friend in Bombay called Parmeshwar Godrej. Do you know her?"). In his commodious courtyard, he had thrown a party during the one-day series. "It was young and wild," he says. But tonight there are only gracious old women and their men in evening jackets, all from the textile industry, standing around a small bar in a corner. They are discussing world peace, the "electric personality of Jinnah" and other things. In such places, the warmth towards India is not unconditional. They insist that the new peace between the two countries is a result of America wielding the stick.If Pakistan has been established as a repentant schoolboy, they would like to foist the same status on India too.

Outside such isolated cocoons of good life, on the city streets, in the autorickshaw driver's sprawling real world where the general sentiment is that the ruling class is full of scoundrels, there are stark similarities to India. There are roads where traffic behaves on a sudden stretch, before First World rules are shed as though the drivers have all seen a signboard saying, "Now become brown men." If someone from Delhi is blindfolded and put on any street in Lahore, for several minutes after he regains sight, he will be very sure he is somewhere in his city. Elegant relics, patches of affluence and, in some parts, bursting human concentration. But there are no cows on the road because they have been consumed.

In a casual body count from a static point on any street in a Pakistani city, the population seems predominantly male with a regular passing of women, many of them in black burqas, their eyes gaping at the world around exactly like in music videos. It's at this level, in this huge slice of Pakistan, that India is truly loved. If the need arises here for a magic line, it is "I am Indian". Even the cop, in his black shirt and khaki trousers—loathed passionately here, a languid reminder of a familiarly corrupt law enforcement system that inspires Pakistani films to brutally kill him in the end—smiles unconditionally and offers to go to great lengths to help. The warmth will die once Indians become a common feature but for the moment a taxi-driver somewhere refuses to accept money though with the hope that the Indian will insist on paying, and a hotel manager somewhere, despite shamelessly ripping off several Indians during the cricket season, seems to be genuinely fond of his guests.

But the Indian has to pay a price. There are these endless sermons on brotherhood and peace. Everybody, even a small-time underworld character, all his metaphors of life describing incest intricately, his pus-filled words coming through rubber-like fat lips, his hands poking constantly at your chest when he is stating the obvious with foolish passion, wants to declare his brain-numbing personal view that Indians are "brothers". The Indian can't walk away from all this right now in Pakistan. Sometimes he has to answer for Sunny Deol's ways too.

Like all Hindi film stars, Deol was celebrated here. But after Pakistan-bashing became his way of surviving old age, he's now one of the most loathed Indians in Pakistan, topping even prehistoric Manoj Kumar and J.P. Dutta. "People forgave him for Gadar, but Maa Tujhe Salaam was just too bad," says Shaan, the most popular actor in Pakistan. It's midnight and he's somewhere in Ever New Studio shooting his fourth film for the day. Of the 28 Punjabi films made last year, Shaan starred in all of them. There are four producers lurking behind the spot boys waiting for a chance to hug Shaan who never charges for an embrace. Saima, the top actress here, is standing in a corner with director Syed Noor. The two are said to be in love. "So this film is woman-centric," Shaan says, chuckling.

Majajan, about an upper-caste man's suicidal love for a nautch girl, goes against the formula in Pakistan. "The formula here is killing a politician after giving him a lot of abuses in Punjabi," Shaan says. Punjabi films dominate at the moment, though four to five Urdu mainstream films do get made in a year. Majajan will cost around Rs 2 crore, a high-end Pakistani film. Shaan, the most expensive actor in Pakistan, charges about Rs 17 lakh per film. "Five actors, four directors, three writers and six cameramen run the film industry here," he says. It's an industry that has long been killed by pirated Hindi film CDs.So the sets of Majajan cost not more than Rs 1 lakh and if director Noor shoots more than 45,000 feet of film roll he will be out of the business very soon.

It's in Lahore that films are made but it's Karachi that people in Pakistan often say "is like Mumbai". It's a mistaken notion. There may be unending old Parsis in Karachi, the Arabian Sea and a vital stockmarket but (if you ask a partisan) Mumbai stands alone as a city, free, alive, rich and nightmarish. Karachi is a small town with a lot of people in it.

The pursuit of alcohol in Karachi yields journalists. The Press Club is a place the taxi-driver doesn't know until a pedestrian guides him accurately: "where there are anti-government demonstrations". Inside the club there are vodka and scotch bottles placed boldly on the tables. Senior journalists sit around and drink. Most of them are influential though not many in Pakistan read papers. The entire circulation of English publications, including The Dawn, The News, other broadsheets, weeklies and magazines, is not more than 2,00,000. (Jang, the largest selling Urdu paper, reaches about 7,00,000 homes, after reducing the official circulation figure to more realistic levels.) English dailies are expensive. The Dawn costs Rs 13 and The News sells at Rs 12, just marginally cheaper than a packet of 20 Pine filter cigarettes. Even Jang costs Rs 7.

In the middle of regular news and headlines that may seem odd to an Indian—"Twenty Kashmiris martyred"—Pakistan's attempt at dumbing down is sometimes splashing pictures of Indian actresses or models. A lifestyle writer, another vapid young girl passing through journalism as her parents look for a groom, mistakes a question on "night life" for sex life. Though she is supposed to be a representation of Pakistan's modern young, she finds it difficult to use the word "sex" while talking to a strange male. She talks in whispers about how "some people" get together, "drink and... they have sexual involvement".

Back in the hotel room, the waiter is euphoric for he has just discovered that the Indian in the room is a Christian. An Indian Christian is a deadly combination for a Pakistani Christian. Without warning, he begins his views on secularism. "I have never felt that I was in danger in Pakistan. It's a truly secular country," he says.

"Since you are a Christian," he is interrupted, "it must be easy for you to get good foreign liquor."

Peter looks disappointed. At the sameness of men.

- Daily English Newspaper 10

- Prepaid mobile connection 2,000

- Local SMS 1.75

- SMS to India 4.60

- Hyundai Santro 3.85 lakh

- Suzuki Mehran (Replica of Maruti 800) 3.1 lakh

- Honda City 6.5 lakh

- Petrol (per litre) 27

- LG 21-inch TV 19,000

- Chicken burger at McDonald's 95

- Smirnoff (1.5 litres) 1,750

- Meal for two (at top end restaurant in Lahore): 540

(All figures for Lahore)