When BR Ambedkar returned to India after doing a PhD in Economics from Columbia University, he had thought his caste would finally cease to matter, but that was not to be. Notwithstanding his educational qualifications, on his return to Baroda, he found it difficult to even rent accommodation. Every query for a room would be followed by a question about his caste, and the door being slammed on his face.

Ambedkar’s life and teachings — the story of his struggle against caste oppression and his efforts to make India a casteless and classless society — is being retold in a musical play — “Babasaheb: The Grand Musical,” organised by the Delhi government. The 120-minute-play, directed by Mahua Chauhan, begins with the birth of the political leader who went on to become the Father of the Indian Constitution.

It takes the viewers through the challenging life of a schoolboy and subsequently a student at Bombay’s Elphinstone College, who faces the question of caste every step of the way. In school, he is sent to the back of the class because the teacher refuses to be in close proximity to a child coming from the lower caste. In college, he is barred from studying Sanskrit, a language meant only to be studied by upper-caste students. But Ambedkar, essayed by actor Rohit Roy, strives to rise above all that and makes his way to Columbia University to discover a world devoid of these biases.

Roy does an impressive job (as do all the other actors in supporting roles) in recreating an iconic personality from the annals of Indian history, with his powerful delivery of dialogues. But his casting does bring back the age-old question of representation in the entertainment industry. Why wasn’t a Dalit actor who has been part of a community that has faced oppression chosen for the role? The play also sheds light on Ambedkar’s personal relationships, and how they contributed to his great journey to promote the idea of equality. It was Ambedkar’s father who inculcated in him a keen interest in reading texts since childhood, and introduced him to the writings of Sufi saint Kabir and Marathi poet Tukaram.

Even as he was discriminated against in school, he found an ally in one of his teachers, Krishna Keshav Ambedkar, a Brahmin. It was this teacher who decided to lend him his surname, “Ambedkar,” hoping that the child would never be asked for his caste again. Quoting a couplet by Kabir, he says, “Jaati na pucho sadhu ki, puch lijiye gyaan” (Don’t ask for a saint’s caste, ask him about his knowledge”).

Integral to Ambedkar’s success was the role of his wife Ramabai, who loved and supported his incessant need to learn more and educate himself further throughout their marriage. Ramabai sold her jewellery so that Ambedkar could go to London where he pursued a degree in law.

Narrated by Teekam Joshi, the play also touches upon Ambedkar’s agreements and disagreements over representation of Dalits with political leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi. Important historic moments like the publishing of the “Mook Nayak”, and the signing of the Poona Pact are also captured well. The play highlights the contributions of Ambedkar towards making India a more open and equal society. Joshi says, “He was one of the most underrated and misunderstood leaders in the country”.

To bring Ambedkar’s story to life, art director Omung Kumar has created a 100-ft stage, including a revolving platform installed with a digital screen that recreates spaces from critical moments in the leader’s life. So, when he was at college in Bombay, the screen showed the corridors of Elphinstone College. During his time at Columbia, the screen would prop up images of the library at the American university.

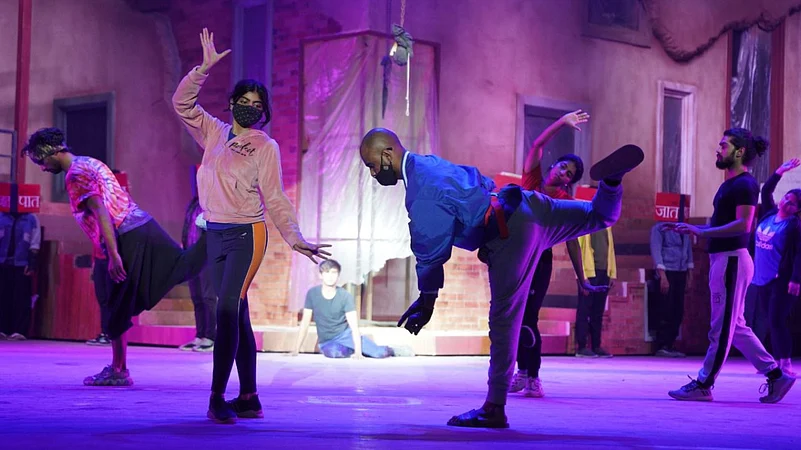

The narrative is interspersed with colourful dance performances to songs written and composed by Kausar Munir and rock band Indian Ocean, respectively. While the choreography, in isolation, is spectacular and powerful in combination with the rousing songs, the opulence of the musical did not seem to complement the sombre narrative of Ambedkar’s life.

One moment you are wrapping your head around the inexplicable challenges a man has undertaken to change the fabric of a country divided in the name of caste, the next moment your eyes and ears are flooded with blinding lights of all colours and thumping bass-heavy music. It is disorienting.

Despite the few shortcomings, it is an important play that needs to be seen. The Delhi government has allowed free entry to the play that will have two shows everyday till March 12. Actor Tisca Chopra, who was moderating the event, said that there were many Indian leaders whose inspirational journeys had been reduced to a few lines in history books. The country knows Bhimrao Ambedkar as the father of the Indian Constitution, but the story of how he got there is rarely told. ‘Babasaheb: The Grand Musical’ is a good place to start.