Mati Diop is a French director, who started her career in films by acting.

Her films move between France and West Africa, fiction and documentary, the contemporary moment and the spectral weight of history.

In 2019, she became the first Black woman to compete for the Palme d’Or at Cannes with Atlantics.

I first saw Atlantics (2019) on a laptop, late at night, not long after its release. I had meant to watch only the opening minutes, but was pulled into its rhythm, the heat rising from the screen, the glances exchanged, and the hum of a city pressed against the sea. By the time it ended, I realised the film had done something unusual: the characters seemed to live both in their own time and in another, older one. Their lives carried the trace of histories I knew from books—but here they were moving, speaking, falling in love, and vanishing. It wasn't that the past intruded on the present; the two were already bound together. That feeling, of people and places suspended between now and then, is what I have returned to in Mati Diop’s work ever since.

Diop’s name began appearing in film festival programmes before it did in the wider press. Born in Paris to a Senegalese father and a French mother, she first worked as an actor in Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum (2008), before turning to directing. Her films move between France and West Africa, fiction and documentary, the contemporary moment and the spectral weight of history. In 2019, she became the first Black woman to compete for the Palme d’Or at Cannes with Atlantics, a debut that confirmed her as one of the most original voices in world cinema. As a filmmaker, her work gives her characters the intimacy of close observation, while holding them in a frame wide enough to register the afterlives of empire.

Her characters—both people and sometimes even objects—who stand at the crossroads of history and the present, carry traces of what has been taken, forgotten, or left unfinished. Whether it is a young woman waiting for a lover lost at sea, an artefact speaking after centuries of silence, or an ageing actor returning to a role that once defined him—they live within the currents of time rather than outside them.

Through them, Diop lets the long processes of restitution, migration, and recognition appear as intimate human continuities. Her films do not rush towards a narrative resolution, which marks the general blueprint of a screenplay. It is so because their worlds are built on unfinished business, like debts unpaid, journeys incomplete, and objects displaced.

In Atlantics (2019), Ada is a young woman in Dakar, engaged to Omar, a wealthy man chosen by her family, while in love with Souleiman, a construction worker building a luxury tower. When Souleiman leaves by boat for Spain with his unpaid co-workers, the camera doesn’t follow him; it stays with Ada. Her life is shaped by family expectations and social codes, but also by the absence of those who have left. Souleiman returns later as a ghost who possesses the living to demand unpaid wages, turning his story into one about unresolved debts—both economic and historical. Ada, meanwhile, continues to live in the city, carrying a private grief within a public role.

In Dahomey (2024), the main figure is a carved wooden statue of King Ghezo, one of the 26 royal artefacts looted by the French army in 1892 and held in a Paris museum until their return to Benin in 2021. Diop gives the statue a voice, allowing it to narrate its own displacement and return. The voice is proud but uncertain, aware of its symbolic importance but unsure of its place in the present. This is set against the debate among Beninese students about what restitution means. Some speak of pride, others of unease; several note that they are having this conversation in French, which is the language of the coloniser. The return has happened, but it is framed by the same systems that enabled the loss or the theft.

In Big in Vietnam (2012), a French-Vietnamese filmmaker is directing Dangerous Liaisons (1988) in Marseille. When the lead actor disappears, she leaves the set and wanders the city. The walk becomes the film's shape, moving through spaces that carry traces of colonial history and migration. The director’s identity is hybrid: at home, in the language and cinematic tradition of France, yet also marked by Vietnam’s colonial history. The film offers no resolution, no “return” to an origin, only a continuation of movement through a present layered with pasts.

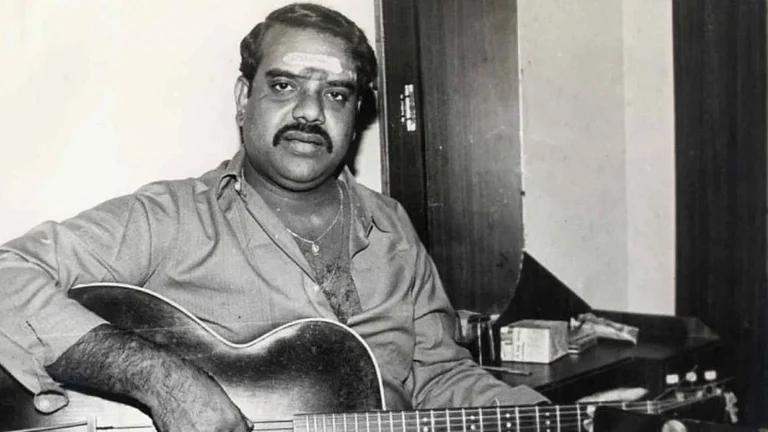

Mille Soleils (A Thousand Suns, 2013) follows Magaye Niang, who starred in Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki (1973). Decades later, Niang works as a cattle herder near Dakar. Diop films him revisiting locations from the earlier film and reflecting on his life. Niang is a living link to a landmark moment in African cinema, but his career never became what one might expect. His image from Touki Bouki circulates internationally, yet his life remains outside the global structures that celebrate that image. The film collapses the distance between the archive and the present, showing the man and the memory in the same frame.

Across these films, these characters could not be more different—a young woman on the cusp of marriage, a ghostly construction worker, a carved royal statue, a filmmaker wandering the streets, an ageing actor looking back on his youth—yet they share a condition.

What binds these lives together is something intangible, a feeling that the past has not gone, that it lingers in the air, in the language, in the texture of things. Each is bound up in systems that bear the imprint of colonial histories: economic structures that push workers to leave their homelands, gendered codes that shape women’s choices, museum networks that determine the movement of cultural objects, the cultural hybridity that defines diasporic artists, and the uneven recognition granted to African cinema’s pioneers. However, Diop resists dramatising this in her films; she observes it with a steady patience, trusting that the audience will recognise the invisible threads that connect the living and the lost, between the now and the before.

Their stories refuse the ease of tidy resolutions. Migration does not end with safe harbour; restitution cannot return a past untouched; cinematic memory cannot lift the constraints of the present. Diop resists turning her characters into blunt emblems of these forces, just as she refuses to strip them of the specificity that makes them human. She keeps them rooted in their own moments and places, yet their lives inevitably open onto larger histories. In her hands, the personal and the historical are inseparable. They move in tandem, shaping and reshaping one another in ways at once ordinary and quietly profound.

This reveals a preoccupation that runs through Diop’s work: an interest in how individuals carry history into the present, not as passive inheritors but as people navigating incomplete transformations. She neither detaches them from their contexts nor defines them only by those contexts. Her films are patient with the fact that many processes of decolonisation, of cultural restitution, of personal recognition, do not end cleanly. By refusing to resolve her characters’ stories in ways that would tidy up history, she keeps the focus on the ongoing nature of their conditions.

Watching a Diop film, one has the sense that the characters are not trying to escape history; they are living within it, negotiating its constraints and possibilities. The movement in her films, across seas, through cities, between archives and the present, is not towards a final point—it is towards a deeper inhabiting of the spaces, where the confluence of the past and present happens.

In the end, her characters remain in motion: Ada looking toward the horizon, Souleiman speaking through another's voice, the statue returning but never the same, the director walking without a fixed destination, Niang standing in a field that was once a set. They carry their histories forward, and Diop’s camera stays with them, attentive to the ways the unfinished past continues to live in the present.