In 2000, Apichatpong Weerasethakul premiered his debut, Mysterious Object At Noon, at the Rotterdam film festival. The hybrid film didn’t make waves instantly—rather, it gained a cult following through the years. Mysterious Object At Noon sweeps through narrative-making in its construction and transmission. How can we prise out the formal machinations of storytelling? Weerasethakul is interested in how stories travel and change appearance as they bend down the trail. Its energy cannot be contained within a finite understanding. A modest film crew travels the breadth of Thailand, pecking through fragments of stories. The debut heralded the sublime, uncanny grace filled in his work.

What Weerasethakul also has in spades is mischief, constantly pushing acts of narration. No single account gains overarching precedence. What we might hold for certain is quickly destabilized and exposed as illusory. Distinctly folkloric in spirit, the film’s high whimsy knows no bounds. It holds up a loose thread—rolling through places, encounters with strangers, mixing up the young and old. There’s a passing of the baton as the story shifts in location and mood. Relying on the surrealist exquisite corpse game, each new participant puts a disorienting spin on an ongoing tale, transmogrifying it in the process. There are performing troupes, the deaf using sign language as well as extraterrestrial objects shapeshifting into impetuous teenage boys. At one point, Weerasethakul himself chips in, insisting that a narrator has free rein over how an anecdote unravels.

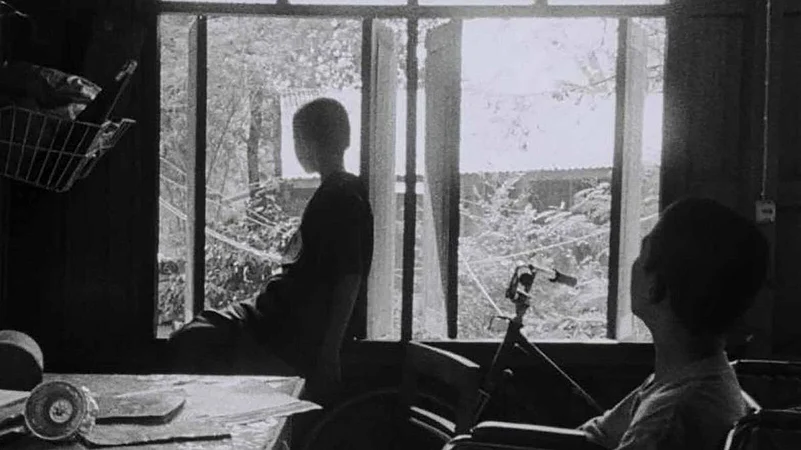

Weerasethakul is obsessed with tweaking structures, mining fresh meaning from a radical refold. Often, the drama moves to jungles—a site of transformation and confrontation. As he mentions in interviews, the jungle reminds him of ancient times, a caveman past. In Thailand, it’s also the space where those suspected of communist ties fled and took refuge. In Tropical Malady (2004), a tender, shy queer male romance abruptly jolts at midway mark. Darkness punctures the screen for a disorienting stretch, receding to tell a different tale. The film turns into forest intrigues, as a soldier hunts for a missing tiger across a village. A wider glimpse at Tropical Malady teases out desire—specifically forbidden desire and what it buries. The soldier chasing the animal becomes a conduit for fulfilling a yearning.

In his cinema, the fantastical sits cheek-by-jowl with the mundane. A dreamlike register lulls us in. Reality doesn’t work within prescriptive, standardizing norms. He views cinema inherently as an “affected medium”. Surreal disruptions and eccentric detours overlay his narratives. They allow him to express freely, ranging from epic secrets to hushed fantasies. His Palme d’Or-winning Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)—the film that put him on the global map—swerves into a bizarre tangent, where a princess has intercourse with a catfish. He wants us to redraw the degree to which we conventionally perceive characters and motivations. Replacing this is an assertion to permit the weird and baffling. The director plays the looniest beats of his films with straight-faced nonchalance. He calls his work belonging to “open cinema”.

Within his cinema, which seems swathed in arbitrariness, he avoids explanations. We’re urged to wander and scramble together a whole from unruly non sequiturs. In a 2010 interview with Guardian, he said, “That’s life. Sometimes you don't need to understand everything to appreciate a certain beauty. And I think the film operates in the same way. It's like tapping into someone's mind. The thinking pattern is quite random, jumping here and there like a monkey." He ties mutations in his work to Thai animist belief. So, transmigrations across human, animal and plants are to be seen as intrinsic, not anomalous.

In Uncle Boonmee…, ghosts who’ve got plenty to say to the living prop up suddenly at dinner tables and linger. There are accounts to settle, things to get off the chest. The preternatural logic governing his cinema suspends skepticism. Yet, at times, it also bracingly flings us back into reality. Till this point in his career, the film has the most politically direct appeal. Uncle Boonmee regrets wiping out scores of communists, as part of the Thai military crackdown. Elsewhere, the present Thai polity is referred to as “a regime that could make anybody disappear”. The setting of the rural north-east, with its history of unrest, ensures the dead only remain at arm’s length. Uncle Boonmee… moves through memory—private and collective—unresolved knots left by death, while the past and present blur. The land bears countless tragedies. It’s tough for people to rake afresh memories of the bloody past. However, Weerasethakul does gesture to them.

Even Cemetery Of Splendor (2015) can be read as a politically loaded elegy to Thailand, looking ahead at the future as well. Set in the filmmaker’s hometown of Khon Kaen, it circles a woman administering a bunch of soldiers under the spell of a bizarre sleeping sickness. The clinic is dotted with light machines said to aid good dreams—the space wrapped in a sci-fi air. The silence is representative of Thai passivity to the dictatorial military junta within which the country has been locked in since 2014. For all their aberrant impulses, his films carry a tactile humility, absorbing all the natural elements. The faintest of ambient sounds intensely reverberate.

Existential mysteries seep into these textures alive to every flickering moment. In his gaze, the world expands beyond the realm of the tangible. Instead, an unearthly enigma takes charge, directing hidden networks. In Memoria (2021), his first film set outside Thailand, Tilda Swinton plays a woman haunted by a strange, abiding sound. She cannot quite put a name to it. Neither is she able to shake it off. Slowly, it sets deep within her consciousness—so inviolably that it crosses from dreams to waking life. Its persistence beckons her out of an invisible slumber. It’s a call to realign one’s life and address what’s lacking. Across his oeuvre, there’s a profoundly calming energy, one that pulls the everyday and unknown cosmos in a unified breath. We watch, agape, as his sensorially rich cinema both relaxes and sharpens attention.