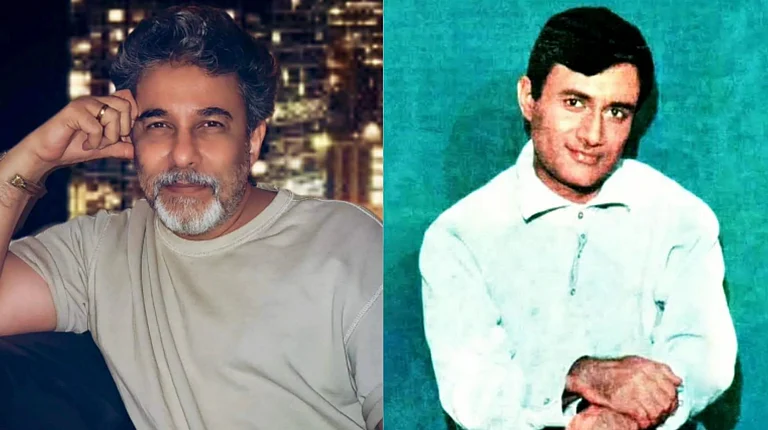

A washerman was responsible for igniting a friendship between two aspiring actors, who are now no more. Guru Dutt and Dev Anand. The duo took their first tentative steps in the world of cinema, in 1945, at Prabhat Film Company, in Poona. Living in the Prabhat quarters, they used the services of a washerman. “It so happened, one day, that the washerman gave me someone else’s shirt,” recalled Anand in an interview I did with him in 1991. “It was while retrieving my shirt that I met Guru Dutt who had been delivered my shirt. He was second assistant to Vishram Bedekar who was making Lakharani (1945) in which he played a small role as well, while I was acting in director P.L. Santoshi’s Hum Ek Hain (1946). Guru also choreographed the dances for Hum Ek Hain, having learnt dancing at Uday Shankar’s academy in Almora. We took an immediate liking to each other!”

Though Anand and Dutt were as unlike as chalk and cheese, they became good friends, sharing similar ambitions. “We had a common dream of making films, he as a director and I as an actor, imagining ourselves to be like a Frank Capra-Jimmy Stewart twosome,” continued Anand, eyes lighting up at the memory, almost 50 years later. With the optimism of youth, they vowed to work together when they became successful. “We decided that if I ever produced a film, I would ask Guru to direct it. And if he directed a film he would cast me in it,” related Anand. “It was a great feeling! Of two talents blossoming together…”

Their friendship continued when they re-located to Bombay, after their contracts with Prabhat ended. A love for Hollywood films made them travel by bus and local train to Churchgate, where there were several modern, air-conditioned cinema halls, like Regal and Eros that screened western films. Sitting in the darkened interiors of Art Deco theatres, Dutt and Anand enjoyed and watched these films keenly. In later years, some of them would be made into Hindi films by Dutt.

“We’d roam around, watch a film, have a cup of coffee and return home,” narrated Anand about their carefree days. “Sometimes, we would walk to the golf links of Pali Hill, where I stayed with my brother Chetan Anand. It was green and serene.” Dutt lived in Matunga, where Anand occasionally joined Dutt for dinner. “We would sit in the kitchen and eat his mother’s delicious cooking,” recounted Anand. Later, in more prosperous times, Dutt bought a large bungalow for himself on Pali Hill and Anand set up office next to Chetan Anand’s home.

These simple pleasures came to an end when both their careers took off; Anand’s before Dutt’s with hits like Ziddi (1948). Dutt spent some time writing stories for magazines, and then apprenticed in direction under Amiya Charavarty and Gyan Mukherjee.

In 1950, Anand joined hands with his director-brother Chetan, to launch their own production house, Navketan. They produced Afsar (1950) with the reigning, singing-superstar Suraiya opposite Dev. Despite this and S.D Burman’s music, the film did only average business. So, for their next venture, Anand invited his friend Dutt to direct a film for his banner. “Guru was a brilliant young man and I had full confidence in him,” stated Anand.

The film Dutt directed for Navketan was Baazi (1951). It was inspired by a Hollywood film, Gilda (1946), and jointly written by Dutt and Balraj Sahani. “The role they conceived for me was that of an anti-hero, but I had no qualms about doing it,” shared Anand. “Roles with a slight negative slant are better than straight goody-goody types. The audience loved me in this role and the film was a super hit!”

Dutt, who had trained under Gyan Mukherjee, famous for his noir films, made a film that the audience loved for more reasons than one. Apart from Anand’s anti-hero role, the ticket-paying viewers enjoyed K. N. Singh’s menacing looks and adored Geeta Bali as a moll. Anand related how Air Force officers in Jodhpur saw the film repeatedly, just to watch Geeta Bali sway sensuously to Tadbeer se bigdi hui, taqdeer bana le, sung by Geeta Roy. The choreography was by Zohra Sehgal, who had taught dance at Uday Shankar’s academy.

Interestingly, Baazi brought together music composer S. D. Burman and lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi for the first time. In the coming years, they would go onto producing many more memorable songs. More romantically, the film brought together Geeta Roy and Guru Dutt, Kalpana Kartik and Dev Anand.

“Guru would confide in me his feelings for Geeta. Later, the two of them got married. When their marriage went through rough weather, I was not in touch with him,” said Anand, whose own romance with Kalpana also culminated in marriage.

The two friends worked together again in Jaal (1952), produced by T.R. Fatehchand for his banner Filmarts. The film was based on Bitter Rice (1946), which Dutt and Anand had seen at Excelsior Theatre. “Guru was very charged with the story of Bitter Rice,” pointed out Anand, adding, “Western films were the order of the day and Hindi films were definitely influenced by them.” The S.D. Burman-Sahir Ludhianvi compositions were a big hit and even today Hemant Kumar’s song Yeh raat, yeh chandni phir kahan is very popular with music lovers.

Both these films made Guru Dutt confident about his directorial abilities and he made Baaz (1953) for producer Hari Darshan. He also faced the camera in this film, as leading man opposite Geeta Bali. “Secretly, he had always wanted to act. He had done small roles in Lakharani and Hum Ek Hain,” observed Anand. “So, the moment he established himself as a filmmaker, he became an actor-director. Though he would approach me with roles, he would ultimately cast himself because he conceived the characters with himself in mind. I didn’t get upset as I was well-established as a hero. Yes, I acted in CID (1956) for his banner, but this film was directed by his assistant Raj Khosla.”

While Khosla shot CID, Dutt directed Pyaasa (1957). Both films were on the floors simultaneously. “Pyaasa was his finest film,” declared Anand. “Basically an introvert, Guru expressed himself better in his films. He had great cinematic vision. A very fine brain, but an extremely restless person. He was, I believe, not very economical with raw stock, shooting and re-shooting till he came close to perfection. The script, too, underwent many changes.”

But before Pyaasa, the introvert made two light comedies, Aar Paar (1954) and Mr. And Mrs. ’55 (1955). After Pyaasa, the brooding filmmaker made his most ambitious film, Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959). Unfortunately the film was rejected at the box-office. “This broke him completely. He just could not take failure,” remarked Anand.

“This is where we were very different from each other,” continued the dapper actor. “What has sustained me in my life is my optimism. I always think tomorrow will be my greatest day. Guru had a streak of pessimism and was very sensitive about public opinion. He couldn’t take criticism or the rejection of his films. Unable to come out of his depression, he asked M. Sadiq to make his next film, Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960). Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962) was directed by his script writer, Abrar Alvi. He totally lost confidence in himself after the failure of Kaagaz Ke Phool. Having tasted tremendous success, he couldn’t cope with failure.”

Anand said he was not aware of the turmoil in Dutt’s personal life, though he did dine with Dutt a few times at his Pali Hill bungalow because he hinted that he was unhappy. “I did not know the intimate details of his life. I only knew this much that he had taken to drinking heavily. And had surrounded himself with people who encouraged him to drink and wallow in self-pity. But I could not advise him as I was no longer that close to him."

“Then, one day, he invited me to his Hughes Road apartment. He said he wanted to work with me. He was pale, thin and emaciated. He looked very melancholic and I could see that he was in no condition to face the camera himself. I assured him I would love to act in his film, and to think of a story."

“Three days later, I was shooting for Teen Deviyan, when I got the news of his death. I cancelled the shoot and rushed across. He died very young. He was only 39. Was it suicide or melancholia, I don’t know," Anand rues.

He wonders, “Had we done a film together, things might have been different. He was at a stage when he was shying away from people; but picking up the threads of our friendship might have pulled him out of his depression. Maybe, we could have revived our camaraderie, and, who knows, done something great together again.”

Alpana Chowdhury is an independent journalist