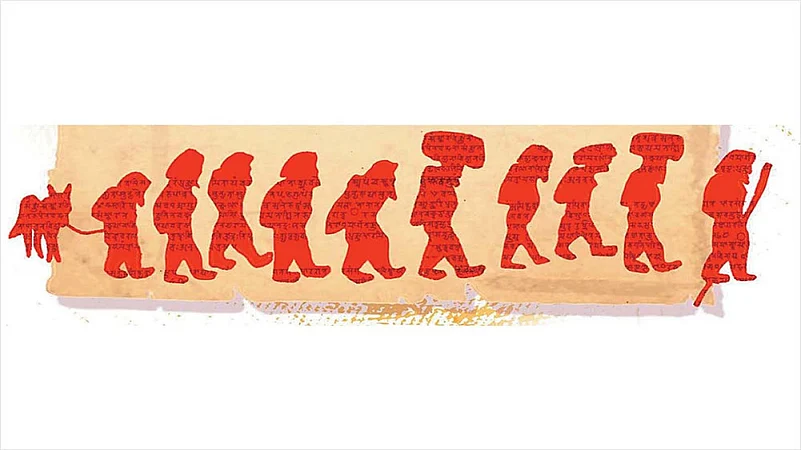

It wasn’t an immaculate conception. After its first hazy origins some 65,000 years ago, the story of Indian languages has been the story of miscegenation, of the mixing of language blood-groups. Sanskrit is as much its child as the old Harappan, or modern Assamese and Malayalam. The traces of that marriage, often conducted on unequal terms, are present everywhere in the swapping of genetic material—especially in the features left behind by an invisible mother. Linguist Peggy Mohan seeks to unravel strands of that mystery in a fascinating new book. Excerpts…

Phertajido o tarphuch tunshong otuntoplo jio. Phor kotrata thuo.

(Phertajido was the first human from the Andamans. He was born out of bamboo.)

This, in a sense, is how far back the story of language in India goes. These are the opening words of the Great Andamanese creation tale, spoken in a language that till just a few years ago was still alive. Humans have lived in India for about 65,000 years, and while we have a record of the languages of the Onge, the Jarawa and the Great Andamanese, we cannot say that these languages are unchanged from what they were when the first Indians arrived from Africa—65,000 years is a long time for a language to stay put. The tribes in the New Guinea highlands, who got there over 40,000 years ago, did drift apart even with no other groups there to influence them, and now speak 800 distinct languages. But Phertajido’s story is still in so many ways our moment of sunrise.

In the second chapter, we imagined a place in the north-west of this subcontinent where a local Dravidian population—remnants of the Harappan Civilisation that had unravelled a few centuries earlier—was joined by men coming in small groups from the Eurasian Steppe about 3,500 years ago, speaking a vernacular variety of the Sanskrit we find in the Rig Veda. Our main source of support for this scenario, along with recent Y-DNA studies, is the Rig Veda itself, which is full of the poetry the migrant men composed, but which tells us nothing about the languages spoken by the people they met, except to say that their speech was ‘garbled’. The sounds of the local languages were unfamiliar to the Vedic men, sounds that must have found their way into the local accent when local people tried to speak Sanskrit.

We know that the Vedic men were patrilineal, because they had patronymics, while the local people they met must have been matrilineal and were referred to by matronymics. From what we know of contact situations in other parts of the world, and Dravidian features that have survived in the sound systems of languages now spoken in the Northwest, we can expect to see strong signs of an old Dravidian gene pool in the people now living in the Northwest. Indeed, local Dravidians should have greatly outnumbered the Sanskrit-speaking men, at the time of first contact, as agrarian communities tend to have high population densities, though the history we get to see is from the victors’ point of view, omitting the details of the people they engulfed. Meanwhile, the other local people would have continued to live on the fringes of this population merger, unchanged in their genetics and their language loyalty.

***

There is a place in India, all the way down the western coast, where we can still see an echo of the old Northwest of our imagination: Kerala. Malayalam, the language of Kerala, is part of the Dravidian language family, though it has grown a thick top coat of Sanskrit. These Sanskrit words have been adapted to the sound system of a Dravidian language in exactly the way the first Prakrits spoken by the earlier people of the Rig Vedic Northwest were.

The presence of Sanskrit in Kerala traces back to the arrival of Namboodiri Brahmins in the region around the eighth century CE, on the invitation of local kings who offered them tax-exempt land grants under a system called janmi if they performed śrauta fire rituals, rooted in the Vedas.

When I decided to bite the bullet and look at a daunting language like Malayalam, the attraction for me was not so much the orderly way in which Sanskrit nouns got mixed into a Dravidian matrix in the Manipravalam era. It was to get a glimpse of the rippling seascape of variation that one could only imagine when all we had to go by in the ancient Northwest was the Rig Veda, standing alone in all its glory as the one and only record of those times. If all we had with us to tell the tale of Kerala was the Rig Veda and the śrauta fire rituals assiduously kept alive by the Namboodiri Brahmin families, would we have had any inkling of the local variety that gave it its sustenance? We would have missed almost everything that was worth seeing!

***

The story of Assamese—the language the Naga traders encountered—is like a prequel to the story of Nagamese. The Ahom people trace their origins back to the Tai-Ahom, who migrated from Southeast Asia and settled in the Brahmaputra Valley in the year 1228. This migration, like so many others in our history, was almost totally male-driven: 9,000 men led by a man named Sukaphaa who set up the Ahom kingdom that ruled Assam for 600 years.

The Ahom, like the Nagas, originally spoke a tone language. This language had its own script, and was related to Shan, the language spoken in the Shan state in Burma where it has five distinct tones. In the beginning, the Ahom formed only a small part of the population of their kingdom, where the majority were local people who spoke other tribal languages or an early form of Assamese. The Ahom migrants initially spoke their old Ahom language, and this remained the court language until the fifteenth or sixteenth century CE. This language has fallen out of use as a spoken language, but it is still used by a small number of priests for ceremonies and rituals.

Soon the Ahom married local women, and had children who grew up speaking the language their mothers spoke, with the Ahom language slowly receding to the status of a language of ritual and the male world of the royal court, losing the feature of contrastive tone and falling in line with the languages of the plains. This scenario—of male migrants marrying local women—is similar to the one we imagined when we looked at the earliest Vedic people in the Northwest around 3,500 years ago.

By the time of Kalidasa, Sanskrit was no longer the native language it had been back in the early days when the Vedic men were composing the Rig Veda. It had become more of a scholarly second language for Brahmin boys. These boys’ first languages, however, like Hindi and the other Indo-Aryan languages all the way west to Balochistan and south to Maharashtra, must have preferred to say things like ‘food-eaten’ rather than ‘I ate’ (in Hindi, this is khaana khaaya, where ‘eaten’ has a masculine ending to agree with ‘food’, even if the actual eater is female; this was not so in earlier Sanskrit, and isn’t so in Bangla). And as writers like Kalidasa did not think they were breaking any rules, sentences like this began to slip in under the radar and even into literature.

***

This strange way of making past tenses, where the verb agrees with the object and not the subject, is found over exactly the same vast area where the Harappan Civilisation once flourished: the north-west of South Asia, going halfway down the western coast of India, taking in the entire Hindi zone and, as we see, extending westward into Iran. We know very little about the people who lived there at that time, except that they seemed to speak languages with retroflexion, which are still there in spirit as the base of all the western Indo-Aryan languages of South Asia. Genetic studies tell us that farmers from Iran came into the Indus Valley and mixed with hunter-gatherers indigenous to South Asia between 4700 and 3000 BCE, and that these Iranian agriculturists “from around the Zagros region had contributed significantly to the ancestry of the ‘Indus Periphery’ population”. This would have produced the people we now call Dravidian—the Dravidians who came into contact with the later Vedic settlers.

Here, now, is an enigmatic twist in the tale, something else that defined these early people, but which is not shared by modern Dravidians.… It is a feature that ends abruptly in the middle of north India, at Banaras, where the substratum shifts in the manner of two tectonic plates colliding at the start of the Magadhan zone.

Out of fragments like these, a hazy image begins to emerge, a faint outline of the people we are trying so hard to find: the Harappan people. It seems that there were indeed languages that came into contact with early Sanskrit, but they are not the same ones we imagine, the ones still alive and well in south India or in the tribal Munda lands. There was, it seems, another strand to the story, which lives on in these tiny linguistic details in the lands where the Vedic people first settled.

(Excerpted with permission from Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India Through Its Languages by Peggy Mohan, published by Penguin Random House India)