The Das family home with its little blue door mounted on a threshold is one of the many inconspicuous houses that line the main road of Lalbagan Padripara in Chandannagar. Its residents, three generations of a former joint family that now meet only on birthdays and funerals (as is the norm with former joint families), are seldom seen together. But on the second Saturday of November, when I happened to pass it by, the otherwise staid house had shed its quiet demeanour and dressed up in a cloak of decadent ‘tuni’ lights.

The clamour of family members, gathered after months of isolation and Covid-anxiety, rang out into the street, making pedestrians turn. The delicious smell of ghee burning wood wafted out the open blue door along with the fumes from the ‘havan’ that made children’s eyes burn.

It was the 60th Jagadhatri Puja celebration for the Das family. What started as a “play-acting” Puja done by children had over the years snowballed into nearly a Rs 1.5 lakh annual tradition. “My family has been celebrating Jagadhatri Puja even before I was born. Earlier, my older brother used to perform the ceremony. I took charge after his death a decade ago,” says 56-year-old Onkar Nath Das, youngest of the three Das family sons. As he watches his grandchildren play around the idol of Jagadhatri in their living room, Nath sighs.

“Ma Jagadhatri means everything to us. It is what keeps this family together,” Das tells Outlook. As an afterthought, he adds, “Not just my family, Ma Jagadhatri keeps this entire town together”. After 60 years, Das family’s Puja is one of the oldest in his neighbourhood. It is also among the nearly 200 Jagadhatri Pujas held in the Chandannagar-Bhadreshwar area in the Hoogly district of West Bengal, some of which are said to be nearly 300 years old.

“Ours may not be an illustrious puja. But it is definitely special.” Nath says. He speaks of the time a woman had come to their house during Jagadhatri Puja a few years ago. Apparently, she had been looking for the Das residence for years but had been unable to find it. It was only on that day, after 4 years of futile attempts to locate the house that she found it. “We didn’t know her, she was not from around. She had done a ‘Mannat’ here at our Puja some years ago. And eventually, when it came true, she felt compelled to come back and offer her prayers and kept coming back because she couldn’t find the right address,” Nath says.

The advent of the Hindu month of Karthik begins with an unusual flurry of traffic toward the quiet, riverside hamlet of Chandannagar which gears up for one of the oldest religious celebrations in India. About a fortnight from Kali Puja (Diwali for much of the country), Chandannagar comes to life to welcome the return of the Goddess.

The Return of the Goddess

There are various origin stories about why Chandannagar and certain other areas of West Bengal, a state which otherwise treats Durga Puja as a staple holiday, celebrates Jagadhatri. An incarnation of Parvati like Durga, Jagadhatri is said to be the manifestation of the omnipresent force driving the universe - Ma Shakti.

It is said that the worship of Jagadhatri started as a way to remind the gods of 'devi shakti' or the divine might of the goddess. After Durga banished evil from the world by killing Mahishasura, the gods of 'Swarglok' became complacent and tried to take credit for the victory. After all, it was the gods who had created Durga in the first place. As a way to remind them of the true power of the goddess, Ma Shakti threw a blade of grass at them as a test.

None of the gods could destroy it. It was only then that the goddess appeared in the form of Jagadhatri, orange with four arms, sitting atop a lion. It is also said that upon seeing the goddess in this form, the egos of the gods melted and transformed into an elephant. Ma Jagadhatri even today is depicted as sitting on a lion stomping an elephant. An ancient metaphor for 'smashing the patriarchy'?

Lights and Lore

It is widely believed that the first Jagadhatri Puja was performed by Raja Krishnachandra Ray, the zamindar of Krishnanagar. The Raja had been captured by the armies of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula for tax evasion. Legend has it that by the time he was released, it was already Vijaya Dashami, the last day of Durga Puja. Saddened at having missed it, the raja decided to start a second celebration by worshiping Jagadhatri. To this day, the festival is celebrated with grand fanfare in Krishnanagar.

If this tale is true, the first public worship of Jagadhatri was celebrated sometime around the 1750s, making it approximately 270 years old. However, local councillor Subhojit Shaw, General Secretary of the Chandannagar Central Jagadhatri Puja Committee, says that the Jagadhatri Puja at Chandannagar’s Chawalpatti predates the one in Krishnanagar. Known as the ‘Adi Ma’ or the ‘First Mother’, the Puja, according to Shaw, was started by agrarian merchants and traders of the area over 300 years ago. “That is the oldest known public Jagadhatri Puja. The second oldest is in Bhadreshwar, which turned 221 years old this year”.

Like Durga and Kali, Jagadhatri is one of the Tantrik deities of Hinduism whose worship gained prominence in Bengal in contrast to Vedic traditions of worship prevalent in northern India. The ninth day and final day of the puja, for instance, continues to witness ritualistic animal sacrifice when goats are slaughtered at the goddess’ altar.

In Chandannagar’s Chawalpatti, a goat has been sacrificed on Nabami at the same spot for over 300 years.

“It’s not for the faint-hearted. I myself have never seen one,” Nabarun Bhattacharya admits. A resident of Bhadreshwar, Bhattacharya has grown up beside Tentultala, which also sees annual animal sacrifice on Nabami. The 30-year-old software engineer, however, is proud of his heritage. “It’s what sets us apart from Kolkata. When the rest of the state is done celebrating Durga and Kali Puja, we still have Jagadhatri Puja” Bhattacharya says.

In Bengali, there is a saying that goes “Baro mash terow parbon”. It roughly translates into “13 festivals in 12 months”. Chandannagar’s Jagadhatri Puja is perhaps the 13th ‘parbon’.

Faith on a Tightrope

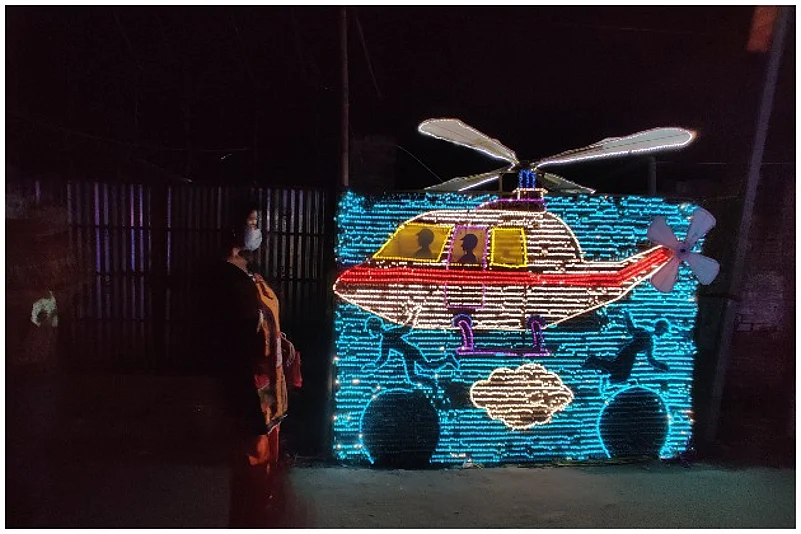

These days, light technicians like Deepak Yadav feel that that grandeur has started to fade. Chandannagar is a hub of lighting with the city pioneering 3-D light art in the country. Artists from the city have displayed their works across the world. And on Jagadhatri Puja, the might of the city’s creativity is on full display.

Yadav, who works with Chandannagar Lights, tells Outlook that these days, many young technicians and artists were moving to Kolkata. "Last year due to the pandemic, many technicians moved to the city or to different professions due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Even this year, the pandemic curtailed budgets of Puja committees, which means less expenditure on lights," Yadav rues.

This year, however, Covid-19 dimmed the lights. While Covid-themed pandals, sanitiser-spraying gates, volunteers distributing masks and strict crowd control failed to dampen spirits, the Puja Committee’s decision to cancel the annual Jagadhatri Puja float - a fantastic procession of 3-D lighting famed to be second only to that in Rio De Janeiro - ruffled many the wrong way. As usual, the anger was directed at political parties.

“If they can hold political rallies, why not let us enjoy the procession?” Yadav asks. "Nowadays, puja pandals in Kolkata try to replicate what we have been doing for years. They were very proud of their Burj Khalifa pandal this year. But not everyone knows that it was a Chandannagar artist who created those lights,” a visibly proud Yadav says.

With the ongoing Covid situation, Yadav wonders if the markets will ever be the same again.

Jagadhatri Puja is an important time for trade for these areas. From light artists to priests, florists, bamboo producers, transporters, hoteliers, and traders, everyone waits for this time of the year to make some profits. Budget cuts were indeed a problem this year, says Shaw. “Chandanagar’s economy depends on the success of the Puja season. Smaller budgets mean less advertising and eventually smaller scale of production which could impact the success of these pujas and harm the city’s heritage in the long run,” Shaw says.

In the din of the crowds making their way through the jewelled gates lining what they call “the Strand”, a woman paced the ground below her 8-year-old daughter on a tightrope. The little girl keeps walking back and forth for hours. The mother says that the girl has been doing acrobatics for two years as school was shut and her father was out of work since the pandemic. For walking six hours on the tightrope, ten feet above the ground, the little girl manages to earn her family somewhere between Rs 300 - Ras 500 on average.

“Festivals like these are the only time for us to display her talent,” the child’s mother says. She says she wants to buy new clothes for her daughter but chooses to not answer when probed about making a minor perform for money. She isn’t the only one. Several little children - almost all girls - tiptoed on tightropes stretched across the city, unfazed by the clanking of coins that were flung into her bowl, unhindered by the phone camera flashes.

Is she an incarnation of Ma Shakti too? The one that the Gods forgot?

Goodbye and Come Again

On the day after the last day, Dashami, the city was in a tired yet defiant state of commotion. After holding up for five days, the skies could not discount further and on November 15, clouds gave way to heavy rain, sending members of residential Pujo committees in a tizzy. For a moment, it looked like ”Bhashan” will have to be cancelled. A local resident who had returned home from Delhi for the Pujas, however, said that the frenzy was normal and that in the end, it will all come together. “People here will give their life for Jagadhatri,” he says.

Sure enough, gigantic plastic wraps come flying out of the secret coffers of committee members. After all, years of practice has made the city well-versed in the performance. The Olympic idols of Jagadhatri are given ‘baran’, wrapped in plastic and then heaved on trucks that will take them on their final journey to Ganga. The power of Jagadhatri - the all-powerful - perhaps transforms mortals into Gods too.

An entire town breaks into dance, in an unchoreographed flash mod. Jiving devotees and revellers descend on streets in a melee, as if to dance away the pain of saying goodbye.

With dusk comes the time for the final send-off. Another year-end. Trucks and cranes swarm the shoreline of Ganga but the enormity of the gods, queued up as if waiting their turn to skinny dip, dwarf all else.

Down below, a string of boats keeps vigil while a designated few remain in knee-deep water, collecting bits of debris, wood and flowers that escaped into the Ganga.

Central Committee’s Shaw says that all the committees in Chandannagar follow environmental guidelines which prevent the complete immersion of idols (made of straw, wood and mud) into rivers. Organizers thus rely on heavy machinery and pure strength of will to get the job done.

The fragility of the divine in the hands of machines is cruel. But modern-day immersions have created something of a balancing act between faith and engineering. As the clay melts away, the structures survive and are reused for making idols of other deities.

And so, the goddess, not unlike hope, lives on.

(All photographs by Rakhi Bose)