Whether you’re a mother or whether you’re a brother, you’re staying alive—unless your community, neighbours, friends and family decide you brought a hex upon them, cursed them, incanted magical spells that can be turned ‘off’ only when you go up in flames or scatter into dust.

That’s what happened to a family of five in Bihar’s Purnea on Monday night: a woman branded a witch was caught by surprise “before she could cause more harm”, and she—Sita Devi—and Babulal Oraon, Manjit Oraon, Aranaia Devi and Kakto were killed by their own friends and neighbours.

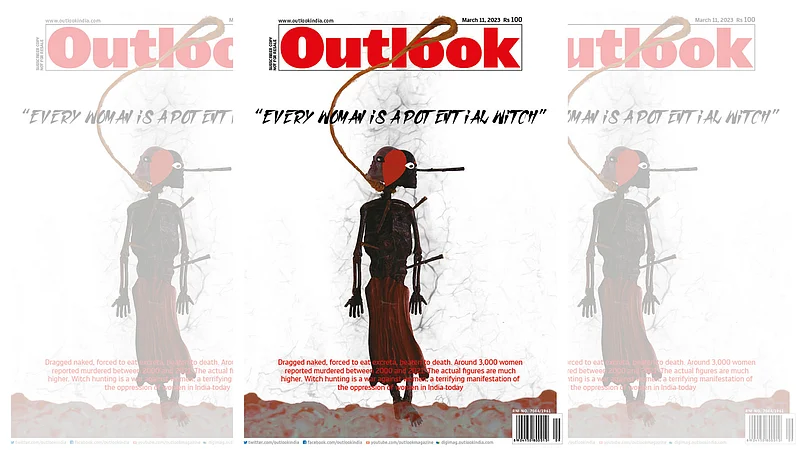

Black magic and witchcraft are barred in India, and special laws protect women in particular from fanatics propelled to kill by superstitious beliefs in the female gender’s nefarious ‘abilities’. And yet, witches are the ones who get blamed for almost everything unfortunate happening in their community, as Outlook Magazine wrote in its 11 March 2023 cover story—Every Woman is a Potential Witch—on witchcraft, those who believe in it and those who become victims of this belief.

‘Nobody heard her screams. The voices of women branded as witches are seldom heard and hence ghastly violence against them in the name of witchcraft has continued unabated over centuries…’ wrote Abhik Bhattacharya and Md Asghar Khan in ‘The Deep Roots of Misogyny’ in the issue.

“It was also common to find victims being forced to leave their village for extended periods of time and, in severe cases, being permanently displaced. Such social and economic boycott debilitates and, ultimately, impoverishes the victim and her immediate family members, who were often collateral victims,” Madhu Mehra of Partners in Law and Development wrote in her essay, ‘The Possibilities Of Legal Redress Against Witch Hunting’.

The headlines may eloquently call the killings in Purnea shocking and tragic, but few parts of India are immune to this malaise—and, it would seem, no religion—as Sunny Sharad wrote in ‘The Mandar Killing Of Women In Jharkhand’: On why he joined the mob, a man arrested for an eerily similar crime committed in Jharkhand’s Mandar said: “Five women from our own village were being termed dayans (witches)... Everyone was leaving their house to join the lynching....I was forced to join the mob because it was a collective village matter. Had I not joined, they could have killed me...”

Govind Kelkar (executive director and professor, Gendev centre for research and innovation, Gurgaon) and Dev Nathan (professor at the Institute of human development, New Delhi) described how understanding the crime—the mindset behind the action—can serve to prevent its recurrence, in their piece on ‘Understanding The Social Basis Of Witch Hunting Is Key To Ending It’.

Their conclusions overturn some popular myths about ‘tribal culture’ and the prevalence of witch-hunting in parts of the country. They write: “Witch hunts, then, are not the result of superstition but of a combination of cultural beliefs and the struggle to create and recreate patriarchy... It is also a clash between an older communitarian ethic and a newer market-based ethic of individual accumulation that brings about… the silencing of women.”

Finally, Jacinta Kerketta recounted her mother’s story of being branded a witch, and a woman once branded as a witch—Padma Shri awardee Chutni Mahato—describes how she saved 140 women from the bitter fate of being lynched as witches.

_.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)