It didn’t need much by way of reading tea leaves for Prasanth Nair to divine what ailed the workers at Priyadarshini Tea Estate—a government venture to rehabilitate indigenous Panniyar tribal families freed from bonded labour at the plantation in Wayanad. Nair—who held additional charge as managing director of the estate after taking over as sub-collector in August 2009—had been clearing a high number of medical reimbursement requests.

“Anaemia was endemic as were tuberculosis and other diseases. I realised most of the workers suffered from malnutrition. They would work all day without proper meals. The women would often forego lunch since their homes were quite distant from the fields,” says Nair, 39. Worsening the situation was the state of “perpetual indebtedness” many families lived in as a result of predatory money-lending practices as well as rampant alcohol and substance abuse. Whenever there was a lockout—a regular occurrence, owing to mismanagement and corruption—families had to suppress hunger with tobacco and areca nuts.

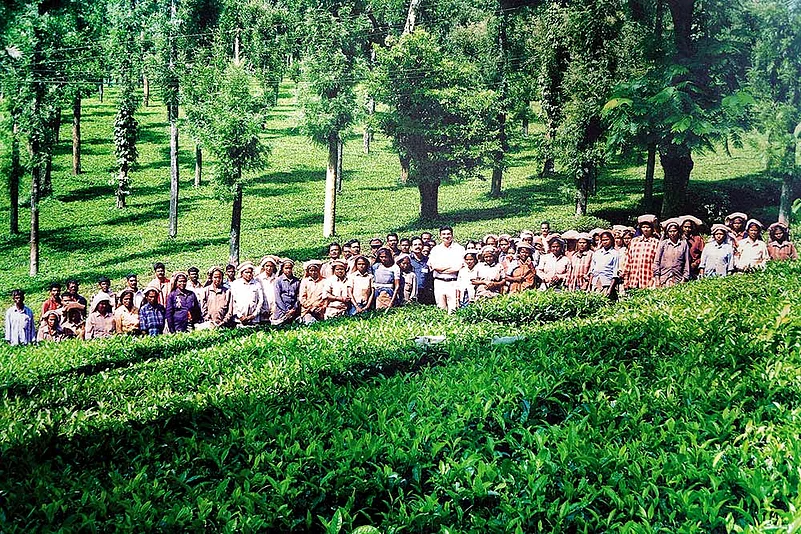

Nair struck upon the idea of linking tourism—the district was a beneficiary of the post-90s boom in the sector but little of this windfall trickled down to its significant adivasi population—to tribal welfare. In 2010, he launched a scheme that would utilise a colonial-era bungalow within the plantation as a tourist resort in order to generate revenue to provide a free noon meal for the workers. “In just three months, medical reimbursements dipped sharply as the simple traditional lunch of rice gruel and bean sprouts began to work its magic. As the scheme and resort grew in popularity, we started serving a full course meal with fish dishes, vegetables and rice. Once the workers no longer had to worry about their next meal, it was a huge burden lifted. The experience taught me the affirming power of food,” says Nair. In his near-two-year tenure, production at the 400-acre estate more than doubled to nearly 15 lakh kilograms per annum from its annual average of six lakh kilograms. As well, worker retention levels improved as fewer people felt compelled, as had been the norm, to seek out greener pastures whether in private estates or out-of-state.

A poignant anecdote underscores both the scheme’s importance and popularity: on his last day at the estate, Nair was asked by an inconsolable elderly woman whether ‘they’ would take away her food when he left. Near a decade later, the mid-day meal scheme still feeds near 400 people daily. In 2015 as the then collector of Kozhikode district, he also launched Operation Sulaimani—a much-celebrated ‘food on the wall’ programme that uses free meal coupons to help tackle both hunger and food waste in Kozhikode.

“In my experience, the greatest obstacle to fulfilling one’s potential is hunger. Does it take a gazetted officer to attest if a person is hungry before he gets a meal? We talk now of right to internet, but it is well past time we understood that food is a basic human right. Being given a meal is not an act of service, charity or kindness. Food is a birthright and as such must be accorded the dignity and respect it deserves,” adds Nair, now the managing director of Kerala Shipping and Inland Navigation Corporation Ltd.

Also Read:

By Siddharth Premkumar in Wayanad