“There are people in our lives who make us happy for the simple chance of having crossed paths. Some of them walk that path beside us, watching many moons pass, while others we barely see between one step and the next. All of them we call friends and there are many types of them.”

—Jorge Luis Borges

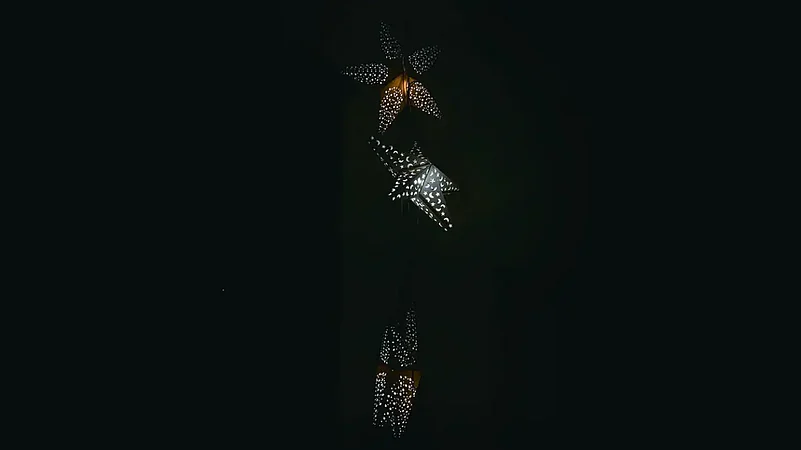

In the evenings, the paper stars are aglow in my house. Seven. For subjects who became friends, who made life less lonely in the small towns and big cities I lived in or visited. They say a reporter can’t be friends with their subjects. But there wasn’t any conflict of interest here. These beautiful people let me into their lives, held me through dreary winters, made me tea and told me their stories. They were the abandoned. People who had difficult lives. It didn’t matter to them if I wrote their stories. It wouldn’t change anything. But they let me in. And stories, if you share them, are like these bonds. A lot has been said about friendships in today’s fractured times. There are all kinds of friendships. Online, offline, with benefits and without loyalties. Not enough about unlikely ones between reporters and their subjects, long after they have moved on. Once a professor at a journalism school said we should never abandon our stories. And when I returned to them after the stories had been written, there was always more to talk about with them. They wanted nothing. I wasn’t looking for a story. These seven stars are about those friendships.

In a mall on a winter night many years ago in upstate New York, with a carousel outside that had all those horses going around in circles shaking off the snow from their backs, I watched a figure walk towards the bus stop.

Frances had said she would be wearing a powder blue sweater. She started her official transition from male to female in August 2001, when she applied for the name change at the Supreme Court for the county of Onondaga. It took her two-and-a-half years to change her name from Frank Mark Fischer to Frances Mary Fischer.

I had come across her in a newspaper story in Syracuse, where I was a student at the university, and had looked her up in the white pages and dialled her number. A man’s voice had answered.

“This is Frances,” the voice said.

“It is a hard life,” she said. “I have big breasts. You will recognise me.”

Frances must be old now. And there must be lots of snow in that city where it must be daytime now.

I lost track of her. In 2006, I met her in her apartment in a housing project in Syracuse.

I had seen the shopping bags, red and pink lace bras strewn around her bedroom.

“I got the unemployment allowance. Thought I’d buy these and celebrate the new woman I am,” she said.

For dinner, she served split pea soup and patties.

I was leaving Syracuse the next day. “Anything helps,” Frances said, when I asked her if I could drop off food items at her place.

She wore a blonde wig with curls. That night, she was wearing bright red nail paint and had painted her lips in a dark maroon shade.

We hugged and promised to keep in touch. She was still managing with her disability allowance when I met her.

“It’s good that I have not shot myself in the head,” she said. “It gets so lonely at times. It is depressing. Sometimes, I want to cuddle with someone on the couch and just watch TV.”

For a year, I kept meeting her on and off. She took me to underground parties where men in drag sang and danced.

Frances was the one who taught me to rejoice in everything. Even in the wrong body.

I named one paper star after her. It is blue. Frances is someone I have written about, someone I kept meeting after the story was written.

I remembered trudging through the snow on some evenings in Syracuse to get to my shifts at the cafe where I worked part-time. Theresa, who knew I didn’t like slicing beef and ham, used to do it for me. She had a crooked leg. I remember I had gone to see her when she was sick and confined to her apartment. She told me how hard it was for a black woman to get by. She would always stand against the wall for support. She had crooked legs and walked with a stick. We took cigarette breaks together. I would hold her coffee when she needed to light up. She told me many things. Most of all, about poverty and what it meant to feel unwanted. We got along. The brown star is for her. She had brown hair with highlights. She always made sure I ate and even packed donuts and muffins for my friends after the shift.

In 2006, I got a job at a local newspaper in Utica. I wrote about the refugees who were being resettled there. I spent most evenings at a Bosnian café called Europa, where they had a jukebox that played old songs. That’s where I formed my first friendships in a lonely town in upstate New York.

I remember San Win and Oh Mar, who had come to Utica from a refugee camp in Thailand after fleeing Myanmar. I met them in Utica in November 2007.

They told me about their job at a laundromat. A sewing company had hired them.

ALSO READ: Bonds And Verses: A Circle Of Urdu Poets

At least, they could buy shoes and warm clothes. We sometimes met even though they didn’t speak much English then.

In 2014, I returned to the town where I once lived to look for those who became my first friends here. Oh Mar and San Win lived next door.

I had left Utica in 2008.

The old house an Afghan refugee family had bought, had undergone a transformation. The youngest daughter of Rahim Jaan Bakhtar was now in school. His two sons had grown up and joined the US Army, and had just returned after spending months in the country they had fled. His second daughter, my friend Bas Bibi, was now in college and drove her own car. The younger son, Nasib Jan, offered to drive me to the Bosnian café.

He fetched two beers and we sat outside, chatting. He had gone back to his country and he saw the streets and the mountains, and he tried to build bridges on his own. But he would always be the Other, he said. They hosted me for the night. Oh Mar had moved to Rochester, but when I called her, she said she would drive down to Utica, where she still had an apartment.

I stayed at her house the next night. We talked about many things. Her brother was now part of a football club. In 2016, he visited me in Delhi on his way to Myanmar. We used to call him Silver Eyes.

I named the white and the red stars after them. And the one big, golden star I called “beautiful friendships”, after the many others I met in the town where I lived by myself. The Somali Bantus, the Bosnians, the Vietnamese, the Sudanese.

I remember the Sundays when I’d drive around, looking into church windows and at empty streets, and stop by the Bosnian cafe with its smell of coffee, bread and Camel cigarettes, where a young man made me Turkish coffee and came out to sit with me. He would smile and smoke. We didn’t speak the same language, but he sat with me.

It felt like home, in between the reading and the wandering. In 2014, he came out with a cup of coffee.

“Hello friend. Long time,” he said.

In 2012, I was in Philadelphia and ended up in north Philly, which everyone tagged as a ‘bad neighbourhood’, with this friend who was also a fellow at UPenn. We hung out with former drug lords, rappers, and writers of what they called street literature. At the bookstore called Black and Nobel that sent books to incarcerated men, I met Tyson Gravity, who sported these dreadlocks. Once Tyson led me to this inner room. He wanted me to take a picture of a charcoal drawing.

“I can hear the waves sitting in this room. I just have to see and hear the waves of traffic and I need not go to California,” he said.

He said the bad neighbourhoods make the soul of a city. Because ‘bad’ is a tag given by those who want to keep the division alive. “That’s what makes a city move... The neighbourhoods. They tell you not to go. Isn’t the sweetest honey guarded by the wildest bees? I can show you such beautiful places,” he said. “I understand the heartbeat of the city. I love the city.”

I met Kenny and read his book North Philly Hustla to make sense of the wild world of the streets. Kenny grew up on Oxford Street and was able to get out of the heady life he had once lived in those streets. As a child, he was fascinated with NPH (North Philly Hustla), which he saw scrawled across walls in his neighbourhood by those who wore gold chains, drove Bimmers and Mercs, and were drug kingpins. Now, Kenny is studying psychology at the Philadelphia Community College. We walked around some of the neighbourhoods in north Philly where he had spent his childhood and youth.

Then there were others like Philly Redface, a rapper who grew up in the streets and sang about the hard life. They taught me a lot. About inner city and racism. Most of all, they taught me not to fear the Other. I am still in touch with a few of them. And on my last day there, Kenny had driven me around in his blue convertible as a farewell treat. The silver star hangs in the memory of my “inner city friends”.

***

The seventh star, a white and blue one, is for the sex workers of Kamathipura in Mumbai, which I first visited in 2012 for a story.

I’ve written about it many times since, but a story is a work in progress. It changes us. Like life. Like encounters. Like love and loss. If loss were to be the measure of love, it had manifested itself there. Every window had a view. Of the streets and the skyline. They also were places where sex workers lean out from. They saw these streets sometimes. I have watched Z, not looking at anything in particular, from the window in her brothel. She stared into the oblivion. A dangerous act. But I always thought these eunuchs were brave. I guess that’s to rationalise the brutality of their existence.

The high-rises have begun to eclipse the sun here. In Mumbai, such ambition is common. Z would always say that I should keep visiting. They taught me resilience.

We shared our stories. We shared food. We became friends.

They taught me to be brave. When I chose friendship over romantic love, I knew that for single people friendships were almost existential in a world designed for couples. The eunuch sex workers told me it was possible. Most of all, these friends taught me that friendship is all about crossing over. And they taught me never to abandon a story.

This issue is dedicated to friendships. Of all kinds.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Difficult Loves")