Historians would baulk at the idea of doing an audit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s 10 years as prime minister even before he has demitted office. They would want to scrutinise the records, study the significant events of his tenure, examine his decisions in the context of national and global trends, and then, only then, offer a tentative assessment. Political scientists are more daring. Since professionally they do not have this luxury of waiting, being called upon, in the here and now, to comment and take positions on the various facets of the working of power, they volunteer a view based on the data available. They read this data through a framework of explanation that has been constructed over the duration of their professional life. Political scientists provide the proto-hypothesis for the scholars of the longue duree.

In the last few days, Manmohan Singh’s prime ministership has been subjected to an insider’s review. Whatever may be the ethical issues involved in Sanjaya Baru’s ‘kiss and tell’ account, it provides us with an inside picture of the working of the PMO. In this essay, I do not want to get into the validity, or significance, of the micro details of Baru’s narrative, of who said what to whom, on which day, in which context, and why. This is good for the tabloids and for breaking news. I want, instead, to offer an outsider’s view of Manmohan Singh’s tenure seen from the perspective of a political scientist concerned with the deepening of democracy in India. I want to bring to the discussion table some important issues of Indian democracy and to see Manmohan’s contribution to them. Ten years is ample time for a PM to leave a legacy.

The first issue on which he must be assessed is his contribution to educating the nation on building a socially just, constitutional democracy. Jawaharlal Nehru did this through his letters to chief ministers, his interventions when matters of rules for the civil service were discussed, the stands he took in his speeches in Parliament and in other fora on several issues such as judicial pendency, scientific temper, big dams, the public sector, non-alignment, planning, etc, and even on minor issues such as the number of cars in the PM’s motorcade. Nehru’s selected works tell the story of a leader who saw himself as the principal educator of a young democracy. He set the standard to be followed by his successors, which unfortunately did not happen since most PMs who followed him, except for Indira Gandhi (about whom more in another article), held brief tenures. Nehru was a man of ideas. He was a student of history. He was a nationalist and a humanist who had a vision of, and for, India in a decolonising world. Through his many public pronouncements, he strove to share that vision with the nation. His life was an excellent school primer from which the nation learnt.

Manmohan had all the ingredients of a Nehru follow-on. From Oxbridge to the Delhi School of Economics to the chairman of the University Grants Commission, to the governor of the Reserve Bank of India, Manmohan had enough opportunity to develop a vision for India and to show it to the nation. And he had enough time, 10 years, in which to play the educator and explain to the nation the direction of their journey and the gains that would follow. But he chose to remain silent. In letter and speech, one finds little record of his vision for India. Having been a student at Oxbridge—both universities have honoured him by naming scholarships after him—he had exposure to the world of big ideas but rarely in these 10 years do we find evidence of where he wanted India to go.

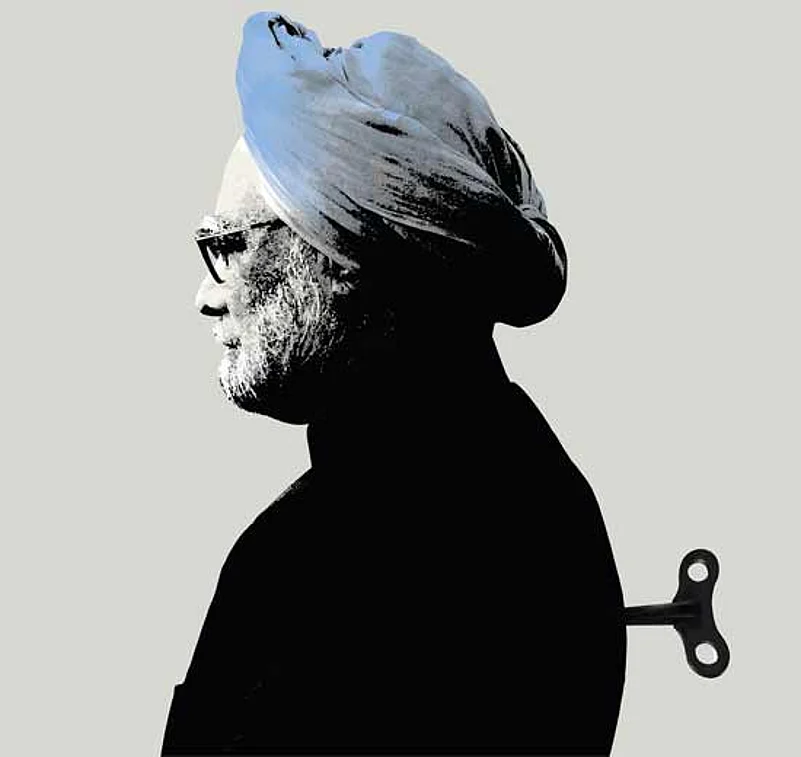

Perhaps Manmohan Singh did not have a vision. As a result of his silence, he reduced the office of principal educator to one of just chief functionary. In a society undergoing complex transformations, such as India, the prime minister must be head teacher to the nation. The India of the 21st century is eminently suited to support such a role for the PM since he has available to him hundreds of TV channels, newspapers and social media sites. He could have been the first blogger PM of 21st-century India but instead he chose to remain in the early 20th century, in silent cinema. By not adopting this role, he left the public discourse to other players, such as breaking news, and to an assortment of political leaders, who responded more to events than to direction. Direction is important for a nation’s journey. Events, by themselves, tell no story. Manmohan submerged the nation in events.

The second set of issues on which we must assess Manmohan Singh is with respect to parliamentary institutions. In his 10 years as PM, Manmohan did not use the prestige of his office to strengthen Parliament as the primary debating chamber of the nation. It is in Parliament where the overlapping consensus, so vital for a diverse nation, is forged through long deliberation. Parliament’s prestige suffered in these 10 years, and while the speaker, the opposition parties and the behaviour of the MPs are to blame for this loss of dignity and legitimacy, a reluctant PM unwilling to contest a challenge, rebut an opposing view, or explain the main elements of his policy to the nation is also to blame. He allowed the undermining of both the political space of Parliament as also of its conventions which are so important for regulating political behaviour.

Another area where our parliamentary institutions suffered greatly is with respect to collective responsibility. As primus inter pares, the PM is not only the first among equals but more, since he enjoys considerable authority to force a decision in a situation of uncertainty. This required him to assert, which he did not do and, as a nation reeled under the many scandals of corruption, we got no leadership from the PM, no statement on steps to punish the guilty, no firmness of moral authority. This indecision led to serious drift in government. Indecision is costly in that it sends out a signal that there will be no price to pay for malfeasance. The predators of the public interest have nothing to fear. One could read such indecision charitably, as ensuring the survivability of his coalition government since confrontation may have put its continuance at risk, thereby seeing it as a utilitarian calculus triumphing against a contractarian logic, but if this is the argumentative road to travel then we must examine the gains of survivability against the costs to the system as a whole. The system paid too high a price for government survivability and will pay a higher price since it paved the way for a majoritarian discourse to replace the diversity discourse that had been so painstakingly built after the demolition of the Babri Masjid and the two carnages of Delhi in 1984 and Gujarat in 2002.

Two small but symbolically significant episodes need to be mentioned here because they did a lot of damage to our democratic fabric. The first is the departure he permitted from established convention with respect to the selection of Chief Vigilance Commissioner P.J. Thomas when he allowed a decision by majority to be taken, instead of by consensus which had become the practice. Such partisanship not only changed the discourse on corruption, with it being alleged that the Congress has something to hide, but also directly reduced the space for bipartisanship in politics. Conventions and bipartisanship are crucial for the working of a democracy.

The second episode concerns the statement of the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, Montek Singh Ahulwalia, that the level of poverty in India was 22 per cent based on a per capita spending of Rs 33.33 a day in cities and Rs 27.20 per day in rural India. This caused widespread outrage and confirmed for many of us that the Planning Commission was pursuing an aggressive neoliberal agenda. The institution had already been infiltrated by global consultancies and this callous remark was only a confirmation of the dominance of their worldview. Where was Manmohan Singh in this public discussion? Why was he absent? He should have publicly censured Montek Ahluwalia for the comment, reminding him that the cost of living in a democracy is linked to a life of decency and dignity and not to a statistical formula whose results fly in the face of common sense.

But absent educator, missing statesman and partisan political leader are not the only entries in his report card. He must also be credited with one major achievement in that he presided over a state that paradoxically did both liberalise the economy and simultaneously roll out the largest welfare programme in human history. By moving his government towards a rights-based development programme—Right to Information, Right to Education, Rural Employment Guarantee, Right to Food and the Forest Rights Act—Manmohan set the basis for a debate on the new welfare state for the 21st century. Growing inequality, within and between states, under two decades of neoliberalism has become the subject of many reports by UN agencies such as ECOSOC, UNDP and even the World Bank. Thomas Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century has become a bestseller because of his thesis about the nature of accumulation. The latest issue of the New Left Review has two articles on rising inequality. Manmohan, of Oxbridge fame, had an opportunity to give the world a comprehensive thesis on a new welfarism. But he missed the chance of theorising this option and building arguments for such a policy regime.

People suggest he was cramped by the other centre of power in 10, Janpath. This is an excuse. If there were fundamental differences between him and Sonia Gandhi, he had the option of exit. He must have read A.O. Hirschman’s classic Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. He chose loyalty. Did he ever face the question that each of us so often confronts, one so memorably captured in Prufrock by T.S. Eliot, ‘Do I dare?’ and, ‘Do I dare?’/Time to turn back and descend the stair. From all the evidence before us he never considered descending the stair. He said once that history would judge him more kindly. I’ve offered five themes on which to judge him: PM as principal educator, PM as primus inter pares, PM as statesman above partisan politics, PM as theorist of a new welfarism and PM as Hamlet. I want, in conclusion, to add a sixth. Because of the opportunities listed above that he did not take, will history see him as the precursor of Modi, the man who paved the way for the most cynical and divisive political leader to become the PM of India? If this happens, History will judge him very harshly indeed.

DeSouza is professor at the Centre for Study of Developing Societies