Pophtaeth, the beloved aunt—my great aunt—was the wisest, the most graceful and the one with the brightest smile, even after her teeth fell off. She was the storyteller, the adviser, the healer and the hafiz. She had stories that no one else did. She dreamt and the dreams always came true. When Papa or my uncles needed spiritual advice, they would go to Pophtaeth the wisest—not only because she saw the future, but also because she saw the present like most didn’t. Her house, the safe haven, was located on the road to the Sherbagh garden, next to the Divibal temple. Me and my siblings spent most part of our childhood around the garden. When there was rain or snow, we would run to Pophtaeth’s house. When the elders came looking for us, for Sherbagh was despised by them, we would run to Pophtaeth’s house. When there were grenade attacks, we would run to her house. When there was firing, we would run to her house. Divibal temple was holy, the army would never enter its street.

ALSO READ: Kashmir: This Isn’t A Postcard Series

For decades, she took care of the temple—every week, she would clean and refill the reservoir, dust the idols, scour the walls, mop the floor and light the lamps. “Don’t enter the temple with your shoes on, don’t go inside with your dusty feet,” she would warn us. “Nagaraj, the snake king will not like it.” I never saw Nagaraj, but I believed it to be there because Pophtaeth said so. She made the temple smell of roses. I once asked her how her street and house smelled so fragrant. “It is the smell of laughter and friendship, my child,” she said. “The streets do not forget.”

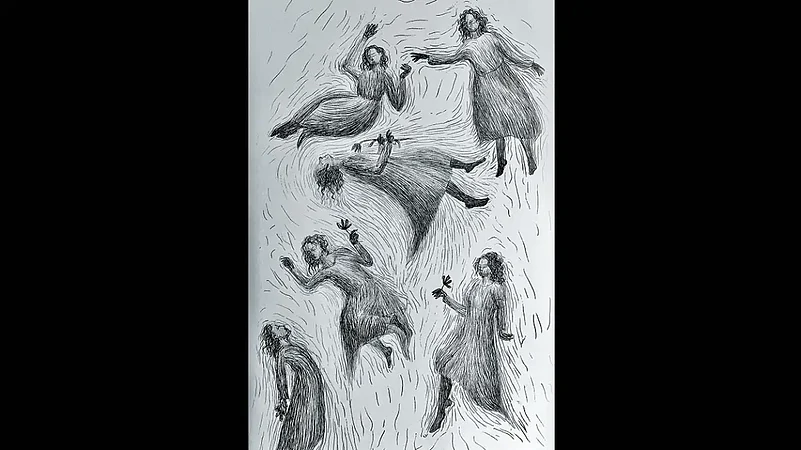

Pophtaeth told many stories—most of them about the things unseen—like her husband ascending to the sky wearing a white robe, the paris (fairies) dancing and singing in Sherbagh, the raantas (witch) burning her leg in place of firewood in the bitter cold, and stories of her friends who had left. I did not know where, but I listened keenly. These were the friends the wise great aunt had grown up alongside. She spoke of them as often as she spoke of her departed husband. She cleaned the temple in their memory—or to fill the void their absence created. In the very rural town of Anantnag, their only meeting spots were the temple, the Sherbagh garden and the Reshimoul shrine. Together, they cleaned the temple and the shrine behind it. Every autumn and winter, they would walk to the Sherbagh garden and bask in the sun.

Their old parents were not very agreeable to their friendship but the young girls kept visiting each other. “The Shivratri’s fish, I cannot forget the taste, it’s like I just took a bite now,” she would say. “Songs, I remember most of them, there is no one to sing along with…but the street still smells of us.” Pophtaeth wasn’t the only one who spoke of missing friends. Ammi, my mother, did too—of her only friend, her best friend Lalleh. I had remembered the name because of Lalleh Ded, the renowned Kashmiri poet. Ammi had lost hope of finding her until one day, walking in Jammu, they ran into each other. They exchanged numbers—now they share recipes, photos and gossip. Ammi and Pophtaeth both spoke of Roshan Lal. “Besides being the best doctor in town, he was a magician; there was no disease he couldn’t cure,” Pophtaeth would recall whenever she felt unwell or weak. Roshan Lal was a healer, and also an immortal. For decades after he left, his house continued to be a landmark; Kaka’s copper shop was next to Roshan Lal’s house, the chicken shop behind it, and now, the ATM, five shops away. For me, the only proof of them being there were the abandoned houses. They were everywhere in the town; many in my mohalla. Batt-waer is a patch of land with old houses, most of them beautiful with intricate woodwork on the windows, just like the houses surrounding Pophtaeth’s home. Some houses still stand tall in Batt-waer.

Pophtaeth said she once had a dream about demons walking towards Kashmir on the Madhopur bridge in Jammu. “They will not cross the Banihal tunnel and yet their stench will be everywhere,” she had declared. Still hopeful for a reunion, Pophtaeth departed. Her house does not smell the same and the fragrance is fading from the street. I walk by the temple, still believing Nagaraj lives there but Sherbagh is not the home to paris anymore. Pophtaeth was right, I can tell; its land is barren. The stench of the beasts resides in the streets.

ALSO READ