On September 13, 1929, a young and fierce revolutionary was martyred at the Lahore Central jail, after a hunger strike that lasted 63 days. It was one of the longest hunger strikes in India’s freedom struggle against the British Raj, to fight the deplorable conditions of prisons that housed Indian political prisoners. Jatindra Nath Das—a member of Hindustan Socialist Republican Association alongside Bhagat Singh, Batukeshwar Dutt and many others—was all of 24 when he attained martyrdom. Honouring his immense sacrifice, democratic organisations across the country commemorate this day as India’s Political Prisoners Day.

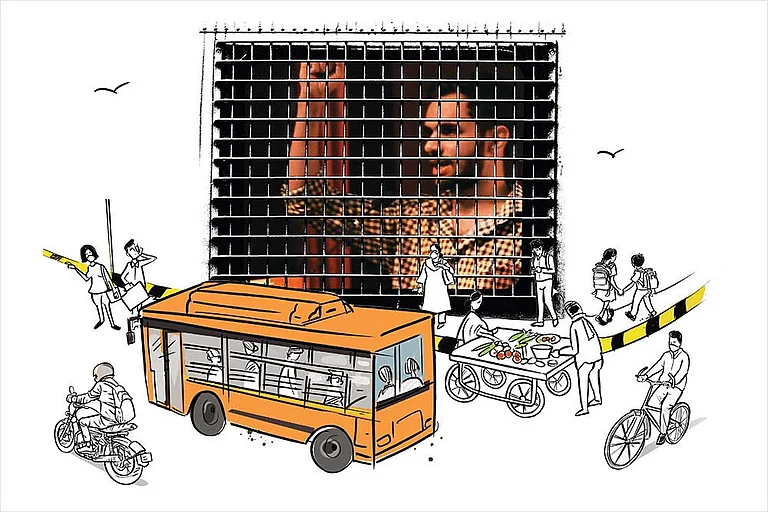

91 years later, another young activist was arrested on the same day by Delhi police under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The same dissent that was criminalised by the British to suppress the anti-colonial struggle nearly a century ago, continues to be treated as a threat even today. Umar Khalid, an ex-student activist from JNU, has been in Tihar jail, New Delhi, since September 2020, on charges of partaking in a “conspiracy” that led to the communal violence in Northeast Delhi in February that year. Along with 17 other activists arrested in FIR 59/2020, Khalid had been at the helm of the anti-CAA protests, which germinated from Shaheen Bagh, New Delhi in the winter of 2019. The popular support and momentum that these protests—primarily led by Muslim women—gained, became a cause of serious concern for the BJP-RSS regime. The anti-CAA movement firmly established that civil disobedience can become a potent method for people to register their dissatisfaction with government action.

It’s been 1763 days since Khalid’s arrest—that roughly translates to nearly four years and ten months, or 42,310 hours behind the prison bars. Times have been extremely trying for his family and friends, as they witness the best years of bright young minds like him being spent in the isolation of jail. But they continue to hold on with dignity, in the hope that one day, these names will be in the clear. As his mother Sabiha Khanum writes in ‘Meeting My Son Umar Khalid In Jail’, “...when tareekh will be written of this time, our sons and daughters will be counted as the ones who did not stay quiet in the face of injustice.”

However, those who remain incarcerated tread more warily around hope. As Khalid writes in his ‘Prison Diary’, first published in Outlook’s January 2022 issue ‘My Dear Apocalypse’, “This uncertainty which keeps us hanging in a state of animated suspension between hope and hopelessness, is especially difficult to cope with. You always remain hopeful that some judge will see through the absurdity of the charges, and set you free. At the same time, you keep cautioning yourself about the perils of nurturing such hopes. The higher your hopes, the higher would be the distance from which you would come crashing down.”

The equal citizenship activists arrested in 2020 aren’t the only democratic voices who have been at the receiving end of police crackdowns in the recent past. Hundreds of kilometres from Delhi, human rights defenders started being arrested in 2018 by the Pune police under the same UAPA. This time, the allegations had involved inciting the violence at Koregaon Bhima in January 2018 and having alleged links with Maoist outfits. Of the 16 activists arrested in the case, Fr. Stan Swamy, the oldest among them, died in custody, awaiting bail. Mahesh Raut, who worked with Adivasi self-governance institutions in rural Maharashtra, is the youngest. Even as he completed seven years in Taloja prison, Mumbai this June, Raut continues to keep his work alive through the assistance he offers to fellow prisoners for their legal cases. Drawing on a survey conducted to interrogate the reasons behind the increasing numbers of young inmates in Indian jails in ‘Inside Taloja Prison: A Study’, Raut writes, “The findings show that the law is wielded as a tool of retribution within a society marked by entrenched class, caste, gender and religious inequalities. This practice results in the perpetuation of the same exploitative and regressive structure that the law seeks to combat.”

As poignantly noble it is to witness these prisoners not giving up their fight for human rights even within the confines of prison, it is still heartbreaking to witness the impact that prolonged incarceration has on their spirits. As Apeksha Priyadarshini writes in ‘My Mulaqat With Umar Khalid’, first published in Outlook’s October 2023 issue ‘All is Well’, “Umar frequently says how prolonged incarceration changes a person fundamentally from within. He says that being caged for a long duration chips away at your restlessness to be free. One starts to forget what life seemed to be like on the outside.”

How soon these defenders secure their freedom will be determined by the arbiters of justice. Regardless, their continuing imprisonment will persist as an indelible taint on the history of a nation state that prides itself as a democracy.