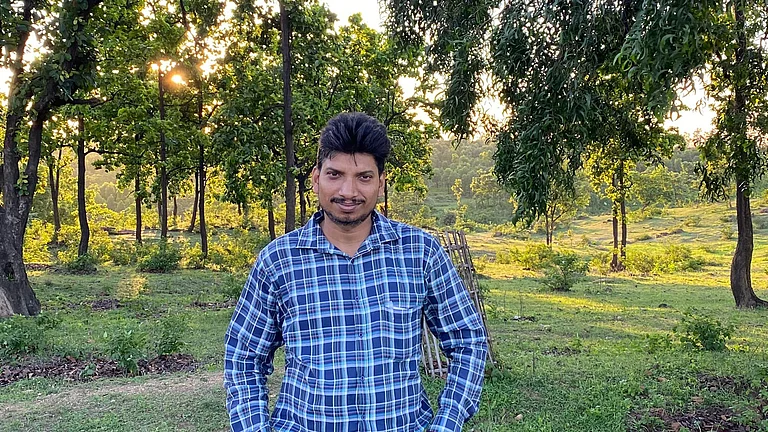

In his complaint filed with the Muffasil Police thana—later converted into an FIR— Sonu Uraon, the 17-year-old eyewitness to the brutal killing of his family, has painted a picture of a chilling, grotesque crime performed by no less than friends, acquaintances and neighbours belonging to his own community.

On the night of 6 July, after dinner at around 10 PM, Sonu was ready to call it a day. Suddenly, 40-year-old Ramdev Uraon walked in with his sister’s son—Sunil Uraon—who was unwell. The accusation came right away: “You are all witches,” Ramdev told Sonu’s mother, father, brother, sister-in-law and grandmother. Then he threatened: “You’ve consumed my son, Sumit, and you now want to swallow my nephew, Sunil? You have half an hour to heal him, or I will burn you all alive.”

Those chilling words began an hours-long ordeal that Sonu is the only one of his family to survive. Shortly after Ramdev arrived, Sunil passed away. Sonu’s complaint to the police has named 23 people who landed up at his house half an hour later, and dragged all his family, including him, towards the pond in his village, Tetgama in the Purnea district of Bihar. He mentions that 150 or 200 people had gathered to bring a brutal end to his closest family.

Sonu lived to tell the tale only because he was able to free himself from the grip of the woman who was dragging him away. His mother, father, brother, sister-in-law and grandmother had been tied with ropes and bound tight, but this woman only held Sonu by his hand. All of them were abused as they made their way to the village pond, and mercilessly thrashed. Once there, the crowd attacked them even more viciously, but as they poured petrol over the others, Sonu managed to escape.

But he never ran far, and hid in the darkness, watching the gory killing unfold—and surviving by the skin of his teeth—to record before the police, at half past midnight, the tragedy he had witnessed.

This brutal killing, based on accusations of witchcraft, has once again exposed how deep-seated superstitions are in many parts of India—especially among tribal communities—about which India never tires of making claims of progress.

Purnia’s Deputy Inspector General, Pramod Mandal told the press after the incident came to light, “It’s hard to believe this can still happen in the 21st century.” It would appear that he is unaware of how prevalent witch-hunting and black magic-related deaths and killings are in India, regardless of the year in which the crime occurs.

As per the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) under the Ministry of Home Affairs, 663 women were murdered between 2015 and 2021 across India after being accused of witchcraft.

Jharkhand, which borders Purnea, has reported the highest number of such killings. However, the official data is riddled with discrepancies. While Jharkhand Police have reported 251 such killings between 2015 and 2021, the NCRB records only 129 cases for the same period in the state. It’s unclear which figure is accurate—but both paint a chilling picture of the reality.

In most cases, the victims are women, and the communities they belong to justify their murder as a twisted form of justice.

In Tetgama, Sonu has recorded seeing not just the cruel murder of those he loved but their bodies being stuffed into sacks, then carried away on a tractor by someone he has not named. Their remains were disposed by the same mob at an unknown location, he records before Police Sub-Inspector Uttam Kumar, the Station House Officer at the Muffasil thana in Ward No. 10 of Tetgama.

Babulal Oraon, Sonu’s father, was something of a self-styled healer—not the officiating traditional healer of Tetgama, but someone people approached for fixing ailments nevertheless. That is how Ramdev’s child, Sumit, was brought to him about ten days previously. Unfortunately, the child died, and when the nephew fell sick too, villagers concluded that Babulal’s family had been practicing witchcraft.

FIR no. 169/25 filed on July 6, amid the tedium of numerous sections of the Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita (BNS) and the Prevention of Witchcraft Act, barely conceals the torture and suffering of those branded wrongdoers based on superstition and brought to a painful, untimely end in Jharkhand and across the country.

A decade ago, in Kanjiya Tola village in the Mandar Block of Ranchi district in neighbouring Jharkhand, five women of a family were murdered after being accused of witchcraft. Like at Tetgama, the villagers used axes, sickles and other farm implements to kill them after they collectively decreed them blameworthy.

In that 2015 case, three FIRs were filed (89/15, 90/15 and 91/15) and fifty, forty-eight and forty-seven people, respectively, were charged under the Indian Penal Code and the Witchcraft Prohibition Act. Nearly 100 were arrested, and charge sheets named forty-three accused in each case. But the cases have dragged on, and most of the accused are on bail.

This raises critical questions: Are arrests and legal proceedings enough to change social norms and beliefs that condone violence, even killing? Why has the government failed to eradicate this violent practice despite years of advocacy?

Reshma, a long-time activist who has extensively researched witch-hunting practices, says, “When does society dare to commit such crimes?—when the government fails in some way. How does society summon the courage to kill?—when the system allows it.”

According to Reshma, neither the government nor the administration appear serious about eliminating this cruel and illegal practice.

According to unofficial data, since the formation of Jharkhand in 2000 and until 2022, around 1,050 women have been killed after witchcraft allegations. That is a large proportion of the overall crimes against women in Jharkhand, which, according to the NCRB, rose from 5,911 in 2017 to 8,110 in 2021.

Despite the scale of violence women face, no central law defines witch-hunting as a criminal offence, though Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam and Odisha have enacted their own laws to combat the menace. Bihar passed The Prevention of Witch Practices Act in October 1999.

Jharkhand still relies on the law passed in Bihar, which it passed in 2001, but is now considered outdated by many specialists in such practices. A stricter law has been demanded—but never passed—as witchcraft accusations continue to haunt victims—and survivors like Sonu.

The Association for Social and Human Awareness (ASHA), which campaigns against witch-hunting, claims that 1,800 women have been killed in Jharkhand over 25 years due to witchcraft accusations. ASHA’s secretary, Ajay Jaiswal, said, “So far, seven states have enacted laws against witch-hunting, but Bihar and Jharkhand have the weakest laws. Three years ago, we submitted a draft of a stronger law to the President, Jharkhand Governor, Chief Minister and a Union Minister, but nothing was done about it.”

On Tuesday, Bihar Police confirmed the arrest of three accused in the Tetgama case, and set up a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to probe what happened. Will it stop these brutal killings over superstition, so that no more Sonus are created?