“Whatever she wrote gave us a new type of pleasure, she widened the light of her language within the unknown borders of darkness a little bit further. People with uncultured minds cannot write anything upon the tombstone of such an artist…She had triumphed over elements which can formally be called difficulties, but this triumph was of a positive kind because it also brought spoils of war. Sometimes her writings seem to glitter in a row like prize silverware. Upon them is engraved: These trophies are the triumph of mind over matter which is both her friend and enemy too.”

— EM Forster for Virginia Woolf

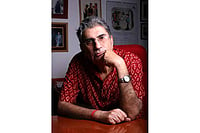

These words were written by EM Forster for his contemporary novelist and critic Virginia Woolf, and these same words after a bit of alteration also apply to the short story writer and critic Mumtaz Shirin, who passed away on March 11, 50 years ago — whose writings are a prestigious capital of the literature of this period.

Shirin writes about the elements that combine in her art and personality at the beginning of her unfinished autobiography. She writes, “Life does not comprise only accidents, events and solid experiences. The intangible change in the biological and mental growth, character and attitude of any individual, the effect of tourism and other cultures, the idea of religion and morals, life (and my life too) is a combination of them all.”

A form of order within these different elements, Shirin was born under the influence of Virgo, the star of sensitivity and intelligence, on September 21, 1924, in Hindupur, a town of present-day Andhra Pradesh. Her father’s name was Qazi Abdul Ghafoor and the name of her mother was Nur Jahan. Her initial life was spent in Mysore where her maternal grandparents brought her up. She attained early education very much at home from her father.

About the features of childhood and the effects on her personality, Shirin writes: “My early mental and to an extent literary training owes itself to the responsibility of my father and my religious and moral training in the shadow of my maternal grandfather…the solemnity, purity and piety of my maternal grandfather; father’s tolerance, liberal ideas, free and contented life, luxury and comfort; mother’s simplicity, innocence, carelessness with the world and inexperience, patience and contentment and seclusion; and the grandmother’s civility, friendliness, popularity, liveliness and refinement, all these contrary effects and qualities are dissolved intangibly within my character and personality.”

Where Mysore for Shirin was the idea of “the city of desire and lost paradise”, there the influence of her maternal grandfather was dominant upon this period of her life, so much that hearing the news of his death, she left her autobiography incomplete.

After doing BA from Maharani College, Mysore, Shirin got married to Samad Shaheen in August 1942. She has termed Shaheen as the dominant influence of the remaining half of her life. About the same time, her literary activities started as well. In an interview she said, “Since childhood, I have had a great taste for reading literary things and I also used to write short stories at a really young age, but I will definitely not regard this period as my literary period. The urge of literary taste in the true sense came in 1942 after my marriage. Since Samad Shaheen himself had literary taste and my library too contained mostly literary books, so when I began studying good literature and my literary taste became stronger, then I became encouraged to write too.”

Shirin’s first short story Angdai (Stretching of Limbs) was published in 1943 in an issue of journal Saqi and she became famous immediately after its publication. Muhammad Hasan Askari wrote that “Mumtaz Shirin is one of those few Urdu male and female writers whose history very much begins with her fame. She did not have to wait to become famous. Rather right after the first short story, she drew the attention of literature-lovers to herself.”

Along with her short stories, Shirin was also interested in the questions of what was being written by other writers, what sort of literature was produced in this period, what should be her attitude about this literature, and what was her place in the wider perspective of literature and man. This interest and association moved forward to assume the shape of Naya Daur which she and Samad Shaheen issued in 1944 from Bangalore. Naya Daur, which was issued from 1944 to 1947 from Bangalore and from 1947 to 1953 from Karachi, had been issued in the manner of Penguin New Writing and was the first Urdu journal in book form. Due to the high literary taste and the beauty of selection of its editors, Naya Daur was regarded as not only among the standard journals of that time but its contents are still referred to today.

Shirin’s first critical essay 1943 Ke Afsane (The Short Stories of 1943) was published in the first issue of Naya Daur which further increased her reputation. According to Askari, “When an essay of hers regarding the Urdu afsana was published in Naya Daur, people became even more startled. This was a totally new thing in Urdu for a female writer to not only write good short stories but also write a reasonable type of critique.” After this essay’s publication, her fame spread across the entire country and many writers wrote appreciative letters to her.

Short story writing, happy married life, reading new books and the responsibilities of issuing a standard journal…these were the center of her activities in that period and their reflection can be seen in short stories like Apni Nagariya (One’s City) and Ghaneri Badliyon Mein (Within Thick Clouds). Her first short story collection Apni Nagariya was published with Muhammad Hasan Askari’s preface in 1947. Shirin achieved successes in the fields of both creation and critique. Therefore she wrote a short story like Aaina (Mirror) which is perhaps her most effective composition; there she wrote an article like Takneek ka Tanavvo (The Variety of Technique) too which was a result of her broad reading, literary awareness, consciousness of literary devices to bring fast-changing life within the grasp of the short story and diction, deep acquaintance of Western, along with Urdu literature. Askari wrote that the element of search and inquiry in this essay represents a literary period.

In 1947 after the creation of Pakistan, Shirin left her native land to come to Karachi where her activities assumed a new direction. She took out the Fasadaat Number (Riots Issue) of Naya Daur and made a special study of short stories written on the riots (afterwards she also made a selection of the best short-stories with the title Zulmat-e-Neem-Roz (Darkness At Noon) for Pakistan Writers Guild but this book could not be published in her lifetime and was consigned to cold storage. In studying these stories, she had criticised the tendency of some writers of acting in haste, writing propaganda without feeling the deep significance and terror of the riots; due to which she developed differences with the Progressive Movement which became more intense when she touched upon the issue of the writer’s loyalty to the state together with Muhammad Hasan Askari.

Shireen’s breadth of reading, awareness of the latest literary trends, and critical consciousness had very much established her superiority from before. She wrote such essays by way of the fulfillment of the official duties of the critic and the completion of the moral and ideological implications of literary criticism, in which she criticised a few basic intellectual defects of the Progressive Movement and presented an ideology of association for writers of a newborn state in that a spirit of national feeling and communal consciousness should be created within Pakistani literature in that its writers should stand by the desires of the nation on the question of the strength, progress, and construction of the community. Like Muhammad Hasan Askari, this idea of hers was an attempt to rouse a new consciousness in the literary tradition of Indo-Islamic civilisation and Urdu. There were objections to this behavior of Shirin and there was great opposition too, but today she seems to be among the leaders of a new literary consciousness.

During the study of short stories written on the riots, Shireen had also become dissatisfied with this single-layered and superficial praise of man which was prevalent at that time. What is man, what is the conflict between good and evil in his nature, while pondering these questions, she turned her attention towards Saadat Hasan Manto and wrote essays like Maasiyat, Masoomiyat’ (Disobedience, Innocence) and Targheeb-e-Gunah Aurat Ka Tasavvur (The Image of a Sin-Induced Woman). She used to say that Manto going even further than the image of natural or original man presents an image of an incomplete man. She began writing a book titled Noori Na Naari (Heavenly Nor Hellish) for the interpretation of this image which she could not complete. Her journey in studying Manto which went further from psychological interpretations to reach mythology is a unique example in modern Urdu critique.

All these changes also affected her short story writing. Prior to this, her world was of a somewhat protected sort. She said about this period of her youth, when the short stories of Apni Nagariya were written: “I had not seen the complexities of life in this period, not confronted the temptations and evils of the world. Now for me the black and white image of good and evil has divided into many colours.”

To blend profound themes like the element of vice in this complex psychological condition, growing technical consciousness and the face of man; or an attempt to conquer death by means of art, she shaped such a story form which has width and depth and the ability to present many sides of reality simultaneously. She determined such short stories to be three-dimensional short-stories and as an example of it had presented Krishan Chander’s Annadata (Giver of Grain) and Aziz Ahmad’s Madan Sena Aur Sadiyan (Madan Sena and Centuries) in addition to her short-stories Megh Malhar and Deepak Rag. There are various opinions present regarding the success of both these long short-stories. For example, Samad Shaheen —who the writer had adjudged her most sincere and harshest critic— said that until mythology is not united with its epoch, its details and poetical beauty do not carry any purpose and meaning; and Muzaffar Ali Syed expressed the thought that due to this a comparative study is definitely achieved but does not lead to the creation of any foresight regarding life or art which is aesthetically or culturally required in this era. If these short-stories are successful in their ingredients and are even a failure collectively, even then the shade of greatness falls on their failure and their importance is secure in their capacity as experiments of a large scale. More than the short stories, people had an objection to the foreword in which the writer had advocated her writing.

Among the experiences which helped in emerging from the protected magical circle of adolescence to search for the incomplete man, Shirin has mentioned viewing the outside world and living among different countries and cultures. She made many journeys and spent time in many countries.

In October 1954, she participated in the PEN international conference in Holland. In 1954 too, she took a course in modern English literature from Oxford University. During her stay in Oxford, she wrote a monograph on Emily Brontë which began when she had done MA from Karachi University. She had felt affinity with Brontë since she has portrayed such deep love in her novel which crosses the borders of death and eternity. In 1958, she went to Bangkok due to her husband’s employment and lived there for three years. In Bangkok, Shirin came across with the experience which became the basis of her short-story Kaffara (Atonement). This short story, which was written in 1962, proved to be the last destination of her fictional journey. She did not write any short story after it.

Kaffara upon which the literary journey ends, its climax is two books which were published about the same period. The second short story collection, Megh Malhar, was published in 1962 from Karachi and a collection of critical articles Meyaar (Standard) was published in 1963 with Muhammad Hasan Askari’s preface from Lahore. Before this, she had translated John Steinbeck’s novel The Pearl with the title Durr-e-Shahvar which was published in 1975. In addition, she also wrote the introduction to a collection of American short stories which was published in 1957 with the title Paap Ki Nagri (City of Sin). She had also translated Camus’s novel The Stranger but this could not be published due to some reason.

In 1963, Shirin went to Turkey with her husband where she stayed until 1967. In the same period, her literary activity began to slow down and when she stayed permanently in Islamabad in 1967, she had cut off from the literary world to a great extent. Its reason being the intense experience of Kaffara, journeys and distance from home, the closure of Naya Daur or something else, this is a period of her literary silence. Besides two brief essays on Manto, she did not write anything. She kept spending a quiet, isolated domestic sort of life. The paralysed central character of Manto’s drama Is Manjdhar Mein (In This Storm) left such a deep impression on her mind that she began to consider it identical to her.

Many observers think that the critic Shirin did not let the artist Shirin thrive and mature, but now the critic of the story had been defeated before the strength of the story. Shirin’s health too had begun to decline in the meanwhile. After repeated attacks of illness, it was diagnosed that she had intestinal cancer. By that time her disease had become incurable. She passed away on March 11, 1973.

Among the projects which Shirin could not finish or her writings which remained scattered in magazines, besides the incomplete book on Manto Noori Na Naari, included translations of foreign stories, a few critical essays, an unfinished autobiography, her own English translations of her short stories Footfalls Echo, booklets on Brontë and Boris Pasternak in English, etc.

The late Asif Farrukhi compiled some of her work while the rest have been admirably done by Professor Tanzim-ul-Firdous —including a critical work on her life and personality published by the Pakistan Academy of Letters which remains the only work of its kind. Between a half-century to her death this year and her birth centenary approaching next year, there is a need for all these scattered works to be published in book form and widely translated so that Shirin’s full literary status can come before us.

(The author is a Lahore-based writer, critic, translator, and researcher, presently translating Mumtaz Shirin’s short stories and unfinished autobiography. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com. He tweets at @raza_naeem1979. The translations in the article are author’s own. Views expressed by the author’s are personal.)