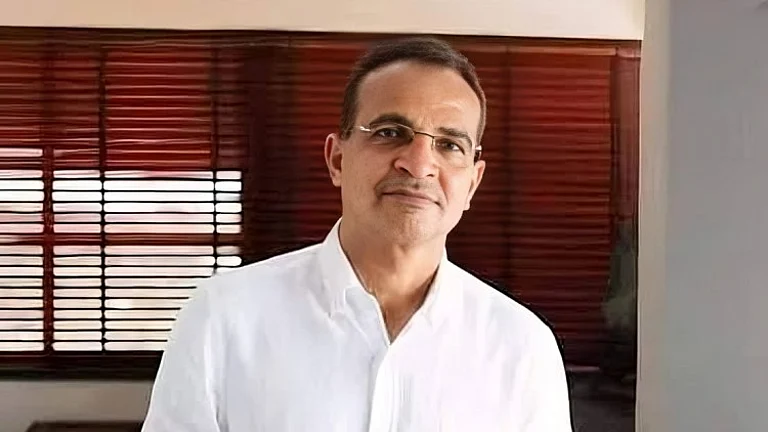

On November 19, 1984, when India announced its first New Computer Policy, Silicon Valley maven Sam Pitroda was no more than a young upstart. He was soon anointed one of the three ‘computer boys’ (with Arun Nehru and Arun Singh) who pushed for liberal electronic and computer policies. Today, India credits Pitroda with telecom pioneer status; but back in 1984, he was among a very few predicting a PCO revolution or teledensity surge. He spoke to Pragya Singh about 1984, the year he came to India.

In 1984, when the New Computer Policy was announced, did you imagine sweeping changes such as the PCO revolution? Looking back at successes and failures, what would you have done differently?

I don’t think we would have done things differently; we’d do things exactly the same way. You see, even though it was 1984, a different time in India’s history when there was virtually no privatisation or liberalisation, we didn’t make technology an end in itself. Our very goal was to create generational changes through technology. Technology was to be harnessed to achieve certain critical goals for India—such as efficiency, reduced costs, increased productivity and improved access. Even now, but especially back around in 1984, access meant everything in India. Education, health, communication and power are denied to millions because they don’t have access. We wanted to change that by using technology.

The immediate realisation was of how long the road ahead would be—at the time, there was no support for localisation, we had a system of import substitution that allowed minimal export of software skills. Anyhow, I had been in constant touch with Rajiv Gandhi and others who had been very encouraging and interested in the plan we laid out, which was over many months’ time. I never felt that it wouldn’t happen, but it was a step-by-step process. Nothing happened in one day.

The ‘computer boys’ were criticised, condemned in 1984. In 1989, you were forced out of C-DOT, your first telecommunications project in India. Do you regret any of it?

I don’t regret it at all. Whatever I was doing was part of nation-building, I was not building a company; it wasn’t personal. It was a more romantic vision, to transform people’s situations through setting up PCOs, STDs, through developing our own exchanges, our own software. I think we all understood at the time that we needed to convince the government of the time that digitisation and creating access were important to India. I look upon that time as a window of opportunity, and we used it to the hilt. When Rajiv Gandhi lost the elections, we knew the window was closing very quickly and that we’ll lose political support. We were clear that this had to happen, because in India politicians are not enlightened. They didn’t have the capacity you need to recognise something is good for the country. The new establishment felt that if Rajiv Gandhi lost the elections, then we should lose too—they never realised that India also loses. Ultimately, the politics could not stop progress. As someone once said, there’s a lot that doesn’t make sense in India but there’s also a lot that does make sense.

Spread that sheet: A computer room in a government office in Delhi, 1984

Rajiv Gandhi was linked with a government policy for the first time in 1984. He still wasn’t a mature politician. Looking back, how much credit would you give him?

In telecom, a lot of the credit should go to him. He understood technology, the need for it and he knew how to cash in on it. He had a lot of interest and we had a lot of experience, and both sides knew what they were doing. And we haven’t done badly; we have a domestic industry that is growing. The PM’s interest carried us forward.

What impacts of the new computer policy are visible now?

We lost a great opportunity at the time, by not taking steps to become a manufacturing giant. China did this carefully and built companies such as Huawei that can compete with the Bells of the world. In India, we created C-DOT to build such competence and it wasn’t in vain. I was at a conference in California a while ago and I found there are hundreds of people, skilled during the ’80s in India, who went abroad with those skills. I heard of 250 in the Silicon Valley, 150 in Washington. So there was a ripple effect.... I’m not cynical. If nation-building is the goal, then it’ll take time. All you can say is: yes, we’re a little slow, but that’s just how we are.

India is not focused on original development and research. We’re focused instead on solving the problems of the rich. That’s because if you’re working on technology development for India, you don’t get the money that an international company can pay for simple, outsourced IT services. So Indian entrepreneurs settle for IT services and the talented people leave. That’s why India solves the problems of (say) Citibank, while the problems of India remain. It’s also very difficult to create an original product. It’s risky. But the rewards are high. Sooner or later, India will realise that for long-term development, these shortcuts will not work.

What’s the road ahead for Indian IT?

We’ve done pretty well in IT but we could do a lot more. It’s essential to be challenged; to use infrastructure more wisely. India has created a huge wealth of professionals, and an equal wealth of fiber-optic cable. Powergrid, gail, bsnl, Railways...they’ve all laid out vast amounts of fiber-optic cable. The next challenge is to use this cable to deliver public services, to manage delivery of essential goods, to provide health and education, to integrate the physical delivery of goods and services—nregs, pds and other systems—using this optic cable. We’re working with the government on this. I don’t see any problem with PSUs being in business. I believe that if there are government-run companies, they are ultimately owned by the public. The more public ownership they have, the more of them that are listed, the better I’d consider it.

'84: Big bang of IT. Hardware prices cut. Software exports on via satellite.

'09: Outsourcing is nation’s calling card. IT, ITES, BPO, KPO, MPO now part of lexicon.