At a time when labour unions seem to be facing a slow decline—official statistics claim the decrease in strikes and lockouts implies improved industrial relations—the stories of these two men define the changing worker-employer equation. Trade union or not, there's no guarantee of being able to get government-stipulated minimum wages, good work conditions or social security of any kind. "Desperation and distrust," says All India Trade Union Congress general-secretary Gurudas Dasgupta, have set in the relations between unions, workers, employers and the government.

But has this mistrust reached a flashpoint as was seen in the recent lynching of an mnc's CEO in Greater Noida? Not many are willing to spell out the possible reasons, though Union labour minister Oscar Fernandes did set the cat among the pigeons by terming it a "warning" for company managements. Other explanations, however, did touch on the seething desperation at the worker level. "There has to be a reasonable amount of humanism in dealing with labour," says Dasgupta. "At present, the system is abjectly exploitative and workers are unable to negotiate a basic settlement."

The irony is that while the unions are shouting that many companies don't pay minimum wages and over-work employees, the number of workers' strikes and lockouts has decreased in the last few decades. "Enterprise-level strikes are generally resolved peacefully. Disputes become violent only in cases of mass retrenchment or if service conditions are bad," says B.P. Pant, secretary, Council of Indian Employers.

Labour leaders recall a few instances where workers have gone on the rampage—like when a Jessop manager was put in the boiler in the '50s or the lynching of a Hutti Gold Mines manager in 1976 or when workers in an Assam tea plantation lynched two managers in 2003. Such incidents have occurred only in extreme circumstances, stress labour experts. "I think the unions earlier were much more militant and dictatorial than today," says a senior HR expert who has had extensive dealings with unions.

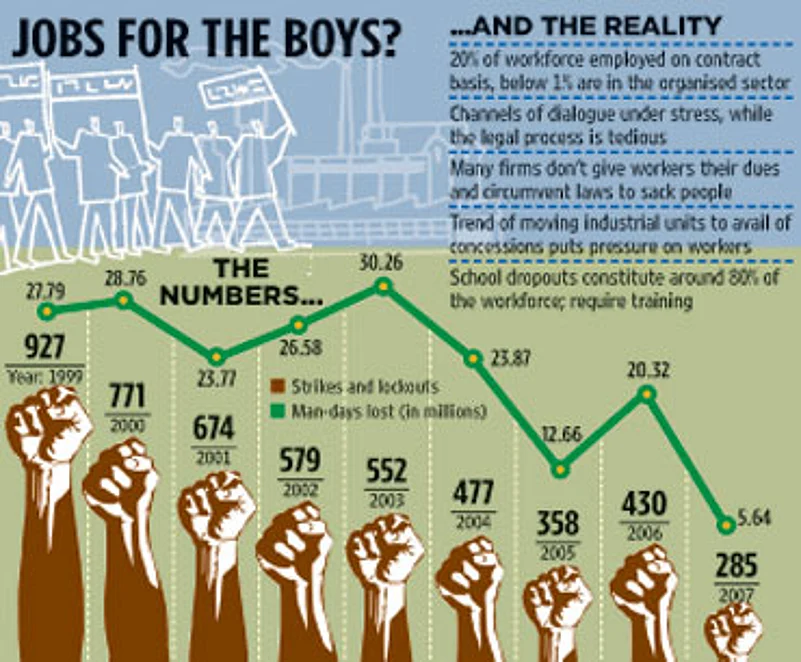

Increasingly, employers have been finding that unions respond and understand the need to win the management's goodwill and get more through negotiation rather than through exerting power. But sometimes, inter-union rivalry or support from outside unions trying to wrest negotiations has been known to result in violent outcomes. "There are no records," says chief labour commissioner S.K. Mukhopadhyay, "but instances of agitating workers resorting to the murder of a CEO are very rare. Instances of strikes and lockouts have come down over the last decade."

Many disagree: the problem arises where criminal politics meshes with political unions in companies that don't consider workers as their assets or invest in their training and development. Says Vivek Monteiro, secretary, Centre for Indian Trade Unions (Maharashtra), "I think trade unions are as active today as they were earlier. However, the problems they are addressing have changed—job security is the prime concern."

With the Centre and many state governments deciding not to regulate or enforce laws related to labour, the employer does have a freer hand today. Some companies misuse this to make a show of providing their workers basic facilities as per law but don't actually implement them. Many of the small and medium units don't even pay basic minimum wages or other health, insurance or severance benefits. The trend of hire-and-fire exists more in the unorganised sector, accounting for over 90 per cent of the workforce. As labour secretary Sudha Pillai admits, "Many companies are trying to go around the laws in the name of flexibility to sack people, many of whom may not be covered by social security due to lapses on the part of the employers and contractors."

Two new trends—factories migrating to places offering tax concessions and the rise in outsourcing non-core activities to contract labour with no proper safeguards—are fostering new sets of concerns. "There is huge stress among workers as industrial capital has become footloose, a deterrent to rooted relationship in a growing industry," says Indrani Mazumdar of the Centre for Women's Development Studies. "Units move off and establish elsewhere but workers can't be as footloose." She cites the case of the garment-exporting Richa Group, which shifted a unit from Delhi to Manesar, forcing 900 workers to commute daily at great cost or relocate to Haryana.

The numbers are staggering. In India, as many as 20 per cent of the 80 million workforce work on contract basis and less than one per cent in the organised sector. To safeguard contract workers, the government is now mulling a legislation on the lines of an EU provision for flexi-security (see interview). "The situation is compounded by the fact that around 80 per cent of the workforce are school dropouts who need social transformation to fit into an industrial work culture," says D.L. Sharma, MD, Vardhaman Yarns and Threads Ltd and a member of the cii industrial relations cell.

As workers seek better opportunities and companies scout for new dynamism and shed workers in the process, a situation of impermanence is being created even among permanent workers. With the process of dialogue breaking down in many cases—and few options to ensure job and income stability—experts warn that we are sitting on the edge of a volcano. Will the political masters rise to deliver long-awaited labour reforms?