Heart Lamp captures the quiet strength of women amidst patriarchal violence.

Mushtaq’s stories reveal the emotional and moral upheavals behind ordinary moments.

Without romanticising struggle, she shows that survival is a form of defiance.

From the very first page, the stories in Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp feel uncannily familiar, as though someone has opened a window into rooms we have walked past all our lives but never truly entered. At first, nothing seems remarkable: men return from long shifts, women tend to do chores and care for their children, families gather around daily meals and shared silences. But as the stories unfold, it becomes clear that something much deeper pulsates beneath these everyday scenes.

Mushtaq resists dramatic language and grand resolutions; she writes from within the slow rhythms of domestic life, reflecting how each ordinary moment holds the possibility of both resignation and revolt. In doing so, she reminds us that resistance need not be loud; sometimes, it can simply entail the act of carrying on with one’s own story, even when the world keeps trying to write another ending.

One of the most striking aspects of Mushtaq’s collection is the way patriarchal oppression is shown as both ordinary and inevitable. In ‘Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal’, the narrator recalls a chilling belief: “Suppose there comes a situation where the husband’s body is full of sores… even if the wife uses her tongue to lick these wounds clean, she will still not be able to completely repay the debt she owes him.” The grotesque imagery shocks, yet Mushtaq presents it not as an exception but as a socially accepted truth. In such a world, devotion becomes a form of debt and love slides into servitude. Still, even within this apparent obedience, moments of disruption emerge. When Iftikhar remarries soon after Shaista’s death, Zeenat dryly warns him: “Do not repeat the declarations of love you made to Shaista with her.” What appears to be a casual remark cuts through the illusion of eternal love, exposing it as something men can transfer at will. Across the stories, women confront not only individual men but the larger systems that legitimise their subordination.

In ‘Fire Rain’, Jameela refuses silence and demands her inheritance: “If you had given me my share then, by now I would have earned ten times the money you spent on my wedding.” Her words unsettle the sentimental logic that equates marriage expenses with care. Her brother fears neither shame nor divine judgment but the threat of losing control over property. Mushtaq thus lays bare the everyday rationality of male entitlement. The brutality of this logic becomes visceral in ‘Black Cobras’. Yakub’s violent outburst sends his wife reeling, the child, Munni, slipping fatally from her grasp. Yet Mushtaq resists sensationalism. Instead, she dwells on the mother’s fractured emotions, her grief intertwined with an unexpected release: “There was no happiness for Munni here…now I don’t have to go behind Yakub begging.” Here, freedom arrives in its most tragic form, implying the impossible bargains women are forced to make.

The emotional horror of conjugal life reaches its most vivid expression in ‘Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord!’, where the narrator directly addresses God. “My body was his playground; my heart, a toy in his hand…He devoured me.” There is no euphemism here. Instead, Mushtaq lets the voice unravel, moving from memory to accusation, from disappointment to pleading.

What makes this monologue so compelling is not just its rawness, but its clarity. The narrator is painfully aware that her suffering is not natural, not deserved, not ordained, despite what religious precepts would like her to believe. She dares to ask God to “be a woman once”, not out of irreverence, but as an act of moral insistence. It is as if she wants the divine to understand that pain is not spiritual; it is material, it has its engulfing weight, texture, smell, and silence. In ‘The Shroud’, one witnesses how a simple promise, to bring back a 'kafan' (shroud) from Mecca, turns into a moral catastrophe.

Shaziya, caught up in her wealth and social status, dismisses old Yaseen Bua’s request with a perfunctory remark: “What kafan, which kafan after falling down dead? Someone or other will put you in a kafan.” When Bua dies, Shaziya’s guilt becomes unbearable. “Only God knows. Shaziya alone knew the truth: it was not Yaseen Bua’s last rites being conducted, but her own.” What is striking here is that Mushtaq never turns Shaziya into a villain. Instead, she exposes how privilege can dull one’s capacity to recognise another’s dignity, and how that blindness is a violence in its own right. ‘Red Lungi’ takes this critique further by linking patriarchy to class disparity. In one of the most jarring contrasts in the collection, we see Razia’s son, Samad, recovering from circumcision under fans and soft mattresses, while Arif, the cook’s son, is circumcised with ash and a bamboo clip. Shockingly he heals faster. Razia’s final murmur, “Khar ku Khuda ka yaar, gareeb ku parvardigaar”, is not a pious platitude.

It is a reluctant confession that God seems to favour the poor because the rich have already insulated themselves with layers of comfort and control.

What makes these stories linger in the mind long after they end is the quiet resilience with which these women carry the injustices meted out to them. The eponymous story, ‘Heart Lamp’, is perhaps the most nuanced example of this. When Mehrun returns to her natal home after her husband abandons her for another woman, her brothers insist she must go back to preserve the family’s honour. But Mehrun, exhausted and bereft, does not lower her gaze the way they expect.

“Amma, don’t I have something called a heart? Don’t I have feelings?...Loving him is a very distant idea,” she says, refusing to accept that a woman’s love must survive whatever is done to her. In that single moment, honour returns to its rightful place, not in the eyes of the community, but in the integrity of the woman herself.

Mushtaq’s writing resists the temptation to romanticise women’s struggles. Her characters are not idealised; they weep, falter, grow resentful, and sometimes collapse under the weight of their circumstances. Yet, this very ordinariness makes their struggles ring true. The moral facet of her stories resists neat binaries of oppressors and victims, showing instead the fragile negotiations of power, survival and hope. The “heart lamp” becomes a fitting image: a flicker carried within, guiding women through their darkness. Justice may remain elusive, yet the narratives affirm that women continue to endure, reflect, and resist with a quiet, persistent strength.

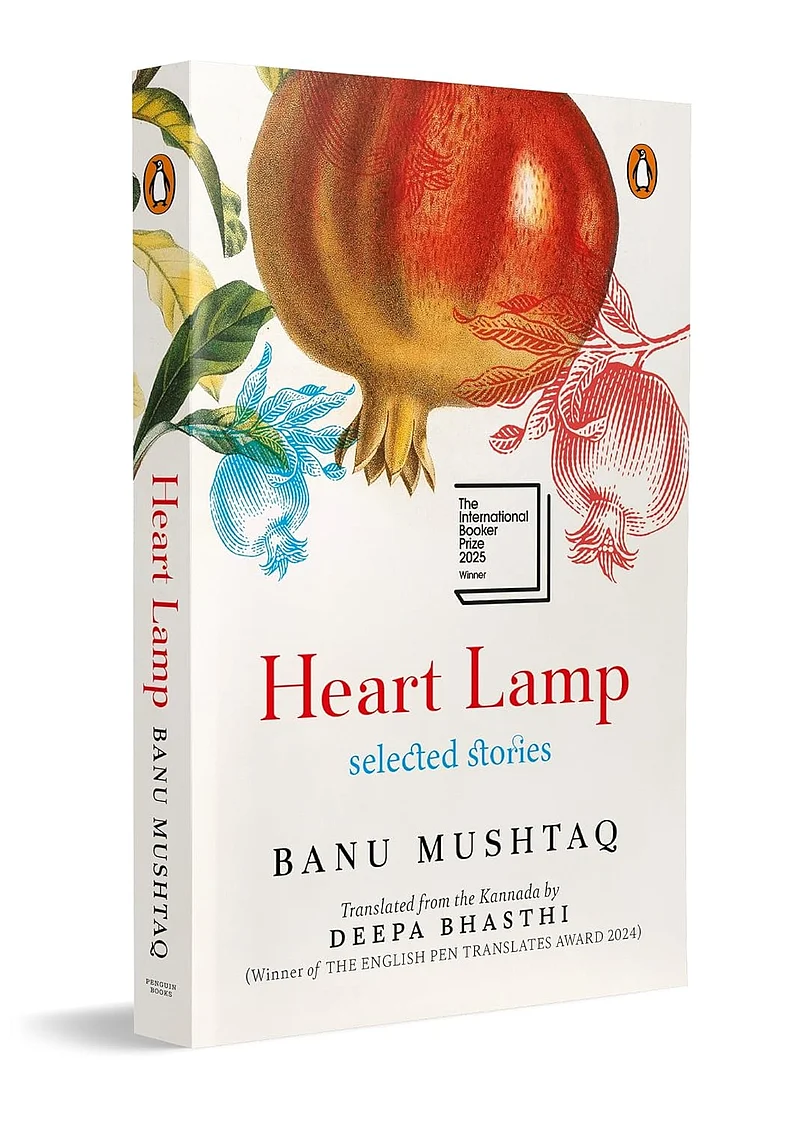

'Heart Lamp' received the International Booker Prize in 2025 for recognising women’s quiet resilience against patriarchal conundrums. In her translator’s note, Deepa Bhasthi writes that these stories are not confined to a single faith or region, but speak to a shared experience of womanhood, where survival often rests on small, defiant gestures. The women in these pages never forget what their lives could have been or still might be. Reading these stories is to carry that faint light forward, not as readers looking in from a distance, but as witnesses standing beside these women in their rooms, their kitchens, their silent moments of refusal. The light is not bright. But it is real. And sometimes, that is enough.

(Priyanka Tripathi teaches English & Gender Studies at the Indian Institute of Technology, Patna)