December 6, 1992. It is the hour after the demolition of the Babri Mosque. Naveen Kishore, the founder of Seagull Books (then in its 10th year), was preoccupied with designing a stage for an Indian music concert featuring Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia on the flute and Ustad Zakir Hussain on the tabla, when he heard a rumour that some people had apparently rushed on to a train from Pune to Bombay, wanting to cut off Hussain’s hands.

With a jolt, he realised that the found objects and ephemeral smoke effects he had been playing with till then would no longer do. So, he reached for an aluminium ‘A’ ladder lying in the theatre, and another ladder and placed them diagonally across the back of the 16x8ft platform covered in black velvet. He placed this platform square on the stage floor that was shrouded in a matte black cloth. He then inserted wooden battens like giant spikes between the different rungs and ripped open reams of blood-red cloth, suspending one end from the black flies (the theatre term for extending stage walls upwards to allow the scenery to be flown upwards till the audience can’t see it anymore) above the ladders, while the other end was used to tie the ladders into knots. The rest of the cloth spilled onto the black velvet, making its way across the black of the floor cloth.

“There was no stopping the blood. It flowed free and uncontrolled. Like a slit artery. It covered the seats bisecting the hall, going into the foyer, up the stairs and onto the street. The audience would have to sit on the bloodied seats.” This ability to visibilise the invisible, admit the inadmissible, be politically incorrect, passionate to make art and publish books that swim against the stream is what Kishore, and by extension Seagull Books, have always represented.

‘The publisher is an accidental historian’

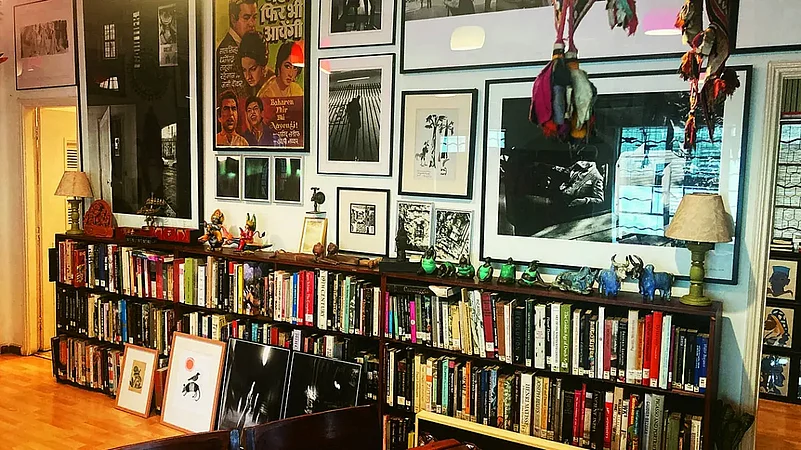

Seagull Books—synonymous with publishing serious, meaningful books from across the world in English translation—was borne out of Kishore’s desire to document the exciting work around him in the arts, cinema and theatre. “The publisher is an accidental historian, who documents the times in a more tangible form. We started 40 years ago, ‘the period of new Indian cinema’, when you had filmmakers Mrinal Sen, Satyajit Ray, Shyam Benegal, Adoor Gopalakrishnan and others. Yet, nothing was getting documented because, in purely commercial terms, for a publisher with many mouths to feed, it was not always the first choice to document the arts. But it needed to be done.” That someone was him, and he has been doing so for four decades now. On June 20, Seagull Books turned 40.

Since 2005, the company has published English translations of fiction and non-fiction by major African, European, Asian and Latin American writers. It now boasts of a backlist of over 700 titles. Beginning with authors such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Jean-Paul Sartre, Roland Barthes, Jorge Luis Borges, Theodor W. Adorno, Aimé Césaire, Thomas Bernhard, Edward Said, André Gorz, Satyajit Ray and Max Frisch, Seagull Books now represents major contemporary writers such as Yves Bonnefoy, Philippe Jaccottet, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Mahasweta Devi, Peter Handke, Pascal Quignard, Hélène Cixous, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Marc Augé, Nabarun Bhattacharya and many more. In 2012, Seagull author Mo Yan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Maryse Condé, whose three volumes Seagull translated and published in English, won the alternative Nobel in 2018.

The company’s success is proof that you don’t need multi-billion dollar investments and offices across the world to have a global footprint. Kishore registered the global publishing house in London, but set up a base in Calcutta precisely to make a point—that location doesn’t matter. From his cosy corner in the Bengal capital, Kishore brings out an annual list of books that is every publisher’s envy. “I have learnt to disrespect the notion of boundaries as these are man-made. But culture travels. Translates. Therefore, we transgress. Not just boundaries but also imagination. We subvert existing frameworks by suggesting different ones. They set up nation-states that ghettoised the book. Make it a commodity. In the publishing world, too much time, energy, and money is spent on creating structures that ultimately box us in.”

‘It has taken us 40 years to get to the point where our books are being noticed’

The soft-spoken, multi-faceted Kishore, however, has remained an enigma in Indian publishing—an outlier almost. Perhaps why you won’t hear of all the times he has put Indian publishing on the global map, including on May 25 when he was awarded the first Cesare De Michelis Prize at the Incroci di civiltà (Crossings of Civilisations) festival—an international literary festival started in 2008—for distinguishing himself ‘internationally through the development of outstanding publishing projects’ for four decades.

Seagull’s translation of Herbert, a novella by Bengali writer Nabarun Bhattacharya (translated by Sunandini Banerjee, a senior editor at Seagull), published in the US by New Directions, received mention in The New Yorker, and glowing reviews in The Washington Post and The Paris Review.

And yet, a few years back, a German journalist who was interviewing Indian publishers in Delhi for a documentary told Kishore, ‘I’m surprised to see that you do all this world literature, because in Delhi everybody said you were a regional publisher,’ Kishore remembers. “People will perceive you as they will, and I will not try to battle that perception. Our work speaks for itself. It has taken us 40 years to get to the point where our books are being noticed. So, it is important to keep doing the work.”

‘The pockets of resistance are always going to be a minority exercise’

Kishore knows about the futility of resistance in the current political climate—and yet resist he must through his words, designs and photos and books. His first book of poems—Knotted Grief (published by Speaking Tiger)—published to great acclaim, was Kishore’s heart responding to the crisis in Kashmir. “It was personal, political, and a national grief. It needed an outlet, and that outlet was poetry.” He says publishing cannot isolate itself from this need of the hour. “The important thing is that stories must carry on—particularly today when governments are trying to stop people from telling their stories, and are instead circulating their own versions of stories. In such a scenario, we have to do the best we can. Till we can. The ‘till’ is not just till we drop dead, which has now become a serious fear of genuinely being halted in your tracks,” he says. “The pockets of resistance are always going to be a minority exercise. There will come a time when that minority is able to influence the masses, but sadly we haven’t been able to do so yet.”

Would he withdraw or retract a book he believes in? “No,” he says firmly. “I would face the consequences of what I’ve set into motion. This is why our contracts don’t have a defensive clause that makes it the author’s responsibility to protect you from libel and obscenity. We believe making books is a collaborative act—when two minds get together. So then, where is the need to protect yourself from something that you didn’t find offensive when you decided to publish it? How does it then just become the author’s responsibility because some other person has taken offence in that work?” But Seagull has withdrawn books too, when it disagreed with the author’s politics. “Somebody who you have grown up reading and admiring their politics, and when the book comes back translated to you, you realise the author’s politics has totally changed…you have no choice but to withdraw the book.”

‘No one can know for certain what people will read’

Seagull wants to be different from the mainstream—not out of arrogance, Kishore says, but because all of that is already being done. “It isn’t about size or scale. It is about making the choice that allows you to risk stepping outside the structures so ‘magnificently’ set up by the world of corporate publishing. To publish books that in our opinion need to exist.” And to find readers who must exist because, “target audiences are a myth”. “No one can know for certain what people will read. It is always after the ‘event’ of the book being bought and read that you grow wise to the fact. Not before.” Meanwhile, Kishore is ecstatic that the English translation of Ret Samadhi won the Booker prize this year, but also pragmatic. “It’s a moment in time where a wonderful book has got world recognition, but I doubt it is going to change the face of Indian translation.”

‘I don’t look back’

You cannot fit the maverick publisher in any box. He does things his way. Like a true visionary, he moves with the times. Like a true legend, he has set a path that many others are and will continue traversing on. He might possess the old-world charms of politeness, integrity and chivalry—but he also constantly reinvents himself, Seagull, and his authors. This includes republishing works by his authors in modern formats such as graphic novels or audio books. Of course, he doesn’t have the time to look back. Even less, look back in regret. “I don’t genuinely look back or feel I could have done anything differently. Yes, there’s always stress and anxiety that is universal to independence. Every new book is like starting again—and sometimes it feels like a treadmill. What balances the treadmill is the joy of doing what we want to do. And the freedom that comes with it.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "40 Years and Counting")

Nilanjana Bhowmick is an independent journalist and author