THE master is back. Nine of Satyajit Ray's endangered early masterpieces—from the pioneering Pather Panchali(1955) to the blemishless Charulata (1964)—have been nursed back to health in a Los Angeles lab. Frame by frame, shade by shade, soundbite by soundbite. And spanking new 35mm prints of Jalsaghar, Devi, Mahanagar and the Apu trilogy are whirring once again to spontaneous applause in many US cities.

Exactly 40 years after Pather Panchali saw the light of day, Ray's formidable worldwide reputation has suffered no erosion, although the prints of his classics have. But back in Calcutta, one bitter man is sceptical about the restoration effort. "I cannot bear to watch Pather Panchali anymore. The available prints are so abysmal that they no longer have any resemblance to the film we made," laments Subrata Mitra, the legendary cinematographer who was Ray's lighting cameraman for 15 years.

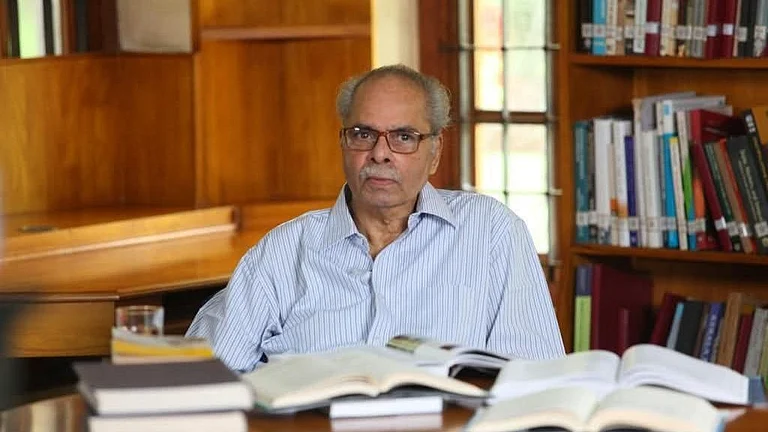

"The restorations have been done mainly from these poor prints. I wouldn't be surprised if the dupe negatives that have emerged from the exercise are worse," says the man who discarded stagey methods of studio lighting and pioneered 'bounce' lighting to give Harihar's typical Benaras dwelling in Aparajito its distinctive feel. "I would be happy to be of help in the restoration process, but nobody has so much as consulted me," says Mitra.

When expatriate Indians and New York's cineastes flocked to the Lincoln Center in April and May to feast on the restored films, many did express annoyance at the few hisses and crackles in the soundtrack and the occasional blackout when the film had to be rewound a fraction and replayed.

Up to 1992, the year Ray was honoured with a special Academy award, nobody knew in just how derelict a state the negatives of his films were. Most were in tatters, some had disintegrated completely. It was the usual story: lack of money and the vagaries of the Calcutta climate. When a film restoration expert visited India that year, he said there was barely another world class film artist whose oeuvre "hung by such a thin thread". Pather Panchali had 15-20 tears per reel, all patched up by tape.

But worse was to follow. A fire in a London film lab destroyed large portions of six already damaged negatives which had been sent in by a concerned admirer and one of the co-organisers of the ongoing US retrospective, film director James Ivory. There was no alternative but to begin patching up these six films from other, also possibly flawed, sources like internegatives, interpositives and prints.

It was at the behest of Ivory and Ismail Merchant that the restoration began. Their sheer persistence helped raise funds for the retro, which has already been to San Francisco, Chicago, Kansas City, Santa Monica and Stanford, and is now showing in Washington. It was their way of saluting the man who, the duo say, launched them as a team by helping them recut their first film, The Householder, in 1963.

"Ray stood behind the moviola crying out 'cut' at the points where the material was to go. This took some getting used to—not so much losing sequences, but the expletive force of the command that blew them away," Ivory recalls.

To restore the films, experts used what is called a "no-noise process" and eliminated most of the scratches that the soundtrack was replete with. "We are happy not only with the response to the retro but also relatively satisfied with the quality of the restoration which time and technological advancement is bound to improve further," says Judith Schell, personal assistant to the Merchant-Ivory team and in charge of their foundation.

"We still get calls from people wanting to know when the retro will come to New York again and whether videos of Ray's films are available. There just seems to be an incredible amount of gratitude for merely having organised the event," says Schell. A master, doubtless, is for ever.