Neglected Corridors

- Elephant corridors have no legal protection under Wildlife (Protection) Act or the Environment (Protection) Act

- Many corridors have now become private land and areas under human use (road/rail)

- There is no dedicated money for corridor protection, experts demand Rs 200 crore for this in the 12th five-year plan

***

The first news despatches brought out all the brutal detail: a goods train, going full throttle, mows through a passing herd of elephants in the Dooars region of north Bengal. It was a clear patch between two stretches of jungle, and a moonlit night, but the train didn’t brake. Toll: seven elephants dead, including females and calves. It may have been the worst such accident India has seen, but the recriminations that followed threatened to eclipse the event itself. It was a familiar ritual, with hard-to-miss undertones of Bengal politics: the state forest department officials filed an fir against the Railways for violating speed limit rules—the train that crushed the elephants was moving at 70 kmph rather than the 30 kmph limit recommended for that forested region. The Railways in turn pointed out that the particular stretch is not officially categorised as an elephant corridor and therefore the speed limit rule did not apply.

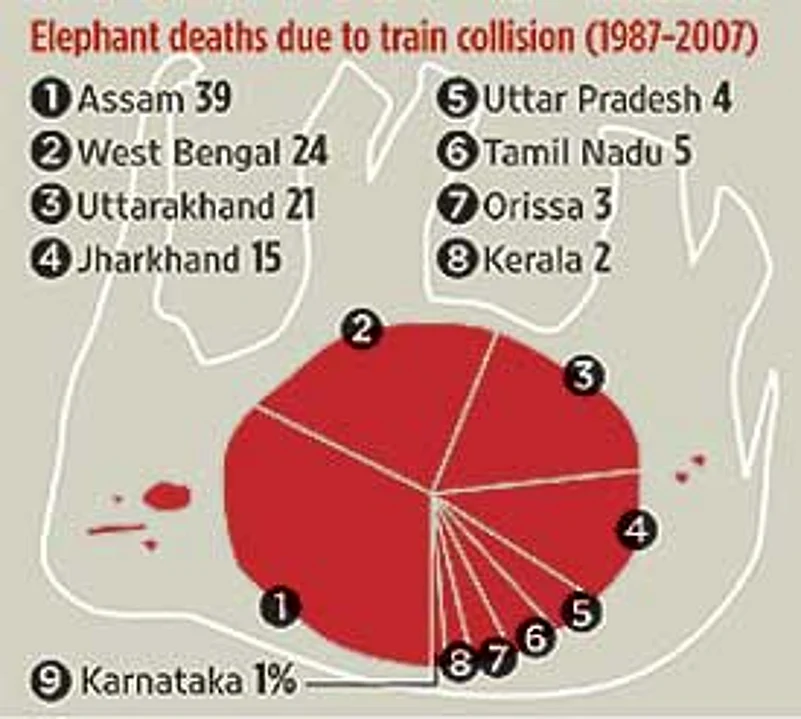

| Source: GAJAH, report of The Elephant Task Force |

Anish Bose, secretary of the Himalayan Nature and Adventure Foundation, says: “While it took seven elephants to die on a single railway track on one single night to grab the headlines, death of animals on the tracks is a regular occurrence here.” According to the most recent census report of the state forest department, 26 elephants have been killed between 2004 and 2008, all hit while either crossing the tracks that run through the forests or while resting on the tracks, unaware of approaching trains.

In the same four-year period, five Indian bisons, three leopards and two Indian rock pythons have been killed in train accidents. Countless other animals such as deer have died but you don’t even hear about these because, unlike elephants, bisons, leopards and pythons, these are not categorised as endangered species. Forest officials say the problem has been compounded by earlier meter-gauge tracks having been converted recently into broad-gauge tracks—these accommodate larger, faster trains. In fact, in 2002, the West Bengal chapter of WWF filed a PIL against the widening of tracks through forest areas. The number of deaths has trebled after gauge conversion. The track on which the elephants died had also recently been converted. It runs through the dense jungle areas between Reti forest and Moraghat forest. On that particular night, the elephants where crossing over from Reti back to their habitat in Moraghat. Locals confirm having heard the herd’s loud trumpets, then the screeching sound of the rail engine as it braked to a halt.

But positive intent, coupled with some ingenuity, can avert such heart-wrenching deaths. Take for instance the Chila-Motichur corridor, near the Rajaji National Park in Uttarakhand, where elephant deaths from railway accidents have been brought down to zero from about 20 in a decade. This happened after the Noida-based Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) collaborated with the Railways and the state forest department to introduce simple, effective measures. “These included cutting down on sharp bends to enhance visibility, making steep railway embankments easier to climb and get off, and creating water bodies in parts of the forests so that elephants needn’t migrate,” says Sandeep Kumar Tiwari, head of WTI’s wildlands division. “So far, we haven’t had a single death and are trying to replicate this elsewhere,” he adds. Other suggested measures include creating passes under elevated railway tracks at spots frequented by elephants.

Human settlements inside forest. (Photograph by Sandipan Chatterjee)

But corridor protection can get more knotty, though not intractable, when humans have to be relocated. The Neoli corridor, located near the Bhutan-Assam border in Udalguri district, was heavily encroached upon; swathes of it were converted into houses, farms and tea gardens. An ashram managed to get itself land allocated illegally. “We got satellite images and mapped them with existing land records to show how they had encroached upon protected land,” says Anupam Sarmah, a senior WWF coordinator. The district administration is now expected to cancel the land allotment to the ashram. “And they are bound to respect it,” Sarmah says. The priority is to reconvert the area into grasslands to re-establish the corridor. In some cases, the WTI even bought corridor land from locals to afford the pachyderms a safe passage. It acquired 25.5 acres of land in Kollegal in Chamarajnagar district of Karnataka and 8.5 acres in Wayanad in Kerala and handed it over to the forest department.

Wildlife corridors are generally neglected, as they are often technically not forest land. However, they offer crucial passage for large mammals between two feeding zones. “Not protecting corridors means you run the eventual risk of reducing wildlife populations to islands with no exchange of genetic material, making them more vulnerable to diseases. You also run the immediate risk of dramatically increasing human-animal conflicts,” says Dipankar Ghose, head of the Eastern Himalaya & Terai programme at WWF India. While the latest deaths pushed Union minister for environment and forests, Jairam Ramesh, to travel to the accident spot on October 2, one just hopes that this time there will be effective action on the ground.

By Dola Mitra in Dooars (North Bengal) and Debarshi Dasgupta