The group of aficionados inspired by Mehta decided to get Champaner its due, through their NGO, Heritage Trust and—what makes this story worth telling—did it with considerably more panache and ambition than you might expect from your average city-based NGO. Shah and Grover, especially the latter, played key roles in a focused two-decade campaign that succeeded in eventually putting Champaner on regional, national and international platforms. The trust mainstreamed Champaner with an international conference attended by eminent archaeologists and architects, got corporate sponsors on board, and persuaded an array of dignitaries to descend on the site. Mallika Sarabhai danced here. The then American ambassador Frank G. Wisner showed up for a General Motors event. Says Thakur, recalling her long association with the group: "It was an unusual mix of people who came together because they cared about their city and their region; active, resourceful, business-like people who got things done. I have had my fights with Karan Grover, but it's the best NGO I have worked with."

It was in the '90s that the group, which had by now helped to stop quarrying at the site, hit upon its winning strategy of internationalising Champaner's cause. "Champaner was not a priority for the state government, getting Delhi interested didn't look easy," recalls Sandhya Bordewekar, the trust's secretary during this period. "That's when we came up with the idea that if Champaner becomes a world heritage site under UNESCO, the government will be duty-bound to protect it."

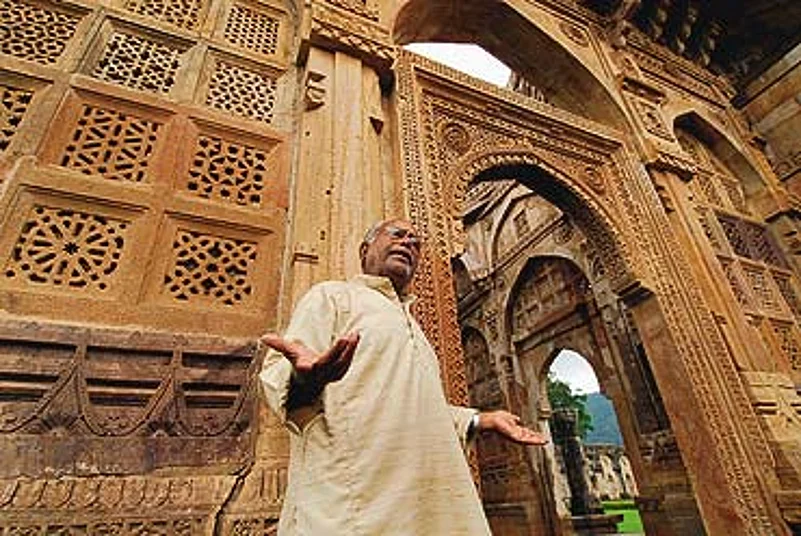

Earth, sky: The Jami Masjid interiors—a Hindu-Muslim blend

With the help of the diplomatic network it had built up, the trust managed to get Champaner nominated to the World Monuments Watchlist of the 100 most endangered sites for 2000. That opened the door for money to document the 120 monuments in Champaner, and paved the way for World Heritage status. But when UNESCO came out with a ruling that a country could only apply for one site in a given year, the trust had to lobby hard for Champaner in Delhi, and even get Jagmohan (then culture minister) to visit the place. In 2004, finally, Champaner was declared a World Heritage site.

Late last year, on UNESCO's recommendation, came a state law, aimed, says Gujarat's culture secretary, V.N. Maira, "at checking unplanned and uncontrolled development of Champaner". The law puts into place an authority that will manage the Champaner-Pavagadh Archaeological Park, consisting of various branches of officialdom, including tourism, archaeology, forests, police, town planning—and the Heritage Trust. Mostly, it's all still on paper, and will take shape, says Maira, after the trust submits its management plan for the site in 2008.

The Act is a significant recognition of the trust's role. "This is the first time a private institution has been mentioned by name in a government law," points out Hasmukh Shah with pride. "To be accepted by the government takes time. We succeeded because we were able to establish our credibility in terms of knowledge base and expertise."

However, there is a touch of irony here. An NGO that networked so well at national and international levels didn't quite manage, Shah concedes, "an effective communication with the local people of Champaner on a continued basis". That is only too evident in the heart of Champaner—the living village inside its citadel—where a debate is currently raging between "pro-heritage" and "anti-heritage" camps. Over tea, we hear a diatribe against Champaner's World Heritage status from sarpanch Kirtida Pandya and her deputy, Mahendra Shah, in which both trust and government come in for flak. (Later, we hear a more optimistic view of the future, from Vinod Patel, sarpanch of the neighbouring village—mainly because he expects land prices to rise because of the archaeological park!) The sore points for the "anti-heritage" camp are restrictions against construction in the protected zone, lack of local consultation, and the communally tinged complaint that Muslim monuments are getting more attention than the Kalika Mata temple and the pilgrimage route. The subtext seems to be that these villagers, who live off the pilgrimage, are yet to see, or be persuaded about, the tangible benefits from heritage conservation. Shah squarely blames local "vested interests" and a notorious BJP rabble-rouser from Vadodara, Niraj Jain, for the "anti-heritage" ferment, but adds, "I would also look within and ask, could we have done more?" A good question. Conservation is a complex business—there are lessons to be learnt, even from a good news story.