Early in 2013, this magazine ran a cover photograph of Rahul Gandhi with the question,‘ Is He for Real?’ Towards the end, it ran a cover with a photograph of Arvind Kejriwal and the statement, ‘Aam Aadmi of the Year’. The journey from Rahul—the question on whom has been answered rather conclusively—to Kejriwal does not just encapsulate the political story of 2013, it also sets the tone for what we may expect in 2014. Both these men have also to be set against the presence of another figure who has dominated the political space in 2013, Narendra Modi. The poll the magazine carried along with the Rahul cover showed Modi (46 per cent) ahead of Rahul (40 per cent) in terms of popular support. In the course of the year, this difference has grown, so much so that the comparison does not even bear a relook.

In September, after much turmoil within the BJP (thanks in the main to L.K. Advani), Modi was finally named the party’s prime ministerial candidate. He hit the campaign trail with the rhetoric expected of him. From references to the shahzada to discussions on Article 370, not much he said was a surprise. He confirmed that he was an effective though somewhat rabid speaker, able in building an immediate rapport with the crowd, but a poor student of history—not just of South Asia, but of his own party. Notwithstanding his lack of knowledge of history or the fact that his home minister was quite illegally willing to depute half the police in Ahmedabad to keep tabs on a woman in whom the BJP says Modi took a ‘fatherly’ interest, he has been picking up support from a huge number of people who were by no means traditional BJP voters, who were concerned not with India’s glorious past but with its abysmal present.

This is the present that has been haunting Rahul. The Congress victory in Karnataka in May was eclipsed once railway minister P.K. Bansal (after a bribery charge against his nephew) and law minister Ashwani Kumar (on charges of tampering with the CBI probe report on Coalgate, filed before the Supreme Court) resigned days after. Much as the Congress tried to slyly deflect the blame on Manmohan Singh, in public perception the distinction between the party and the government was unimportant.

The run-up to the assembly elections in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Delhi was marked by a clumsy and belated attempt by Rahul to distance himself from the UPA-II government. While tearing up the ordinance aimed at protecting convicted politicians in a rather theatrical performance at the Delhi Press Club, he had overlooked the prime minister’s presence in the US at that precise point to meet Obama. This lack of foresight was in keeping with the steps that have marked his rise in the party. The worse he does, the more impressive his designation. The response to his campaign speeches during the recent state elections was, even by his rather minimal standards, dismal. Given that he is already vice-president of the party and his mother is president, it is only fitting that the assembly debacle is likely to be rewarded with him being made the prime ministerial candidate of the Congress.

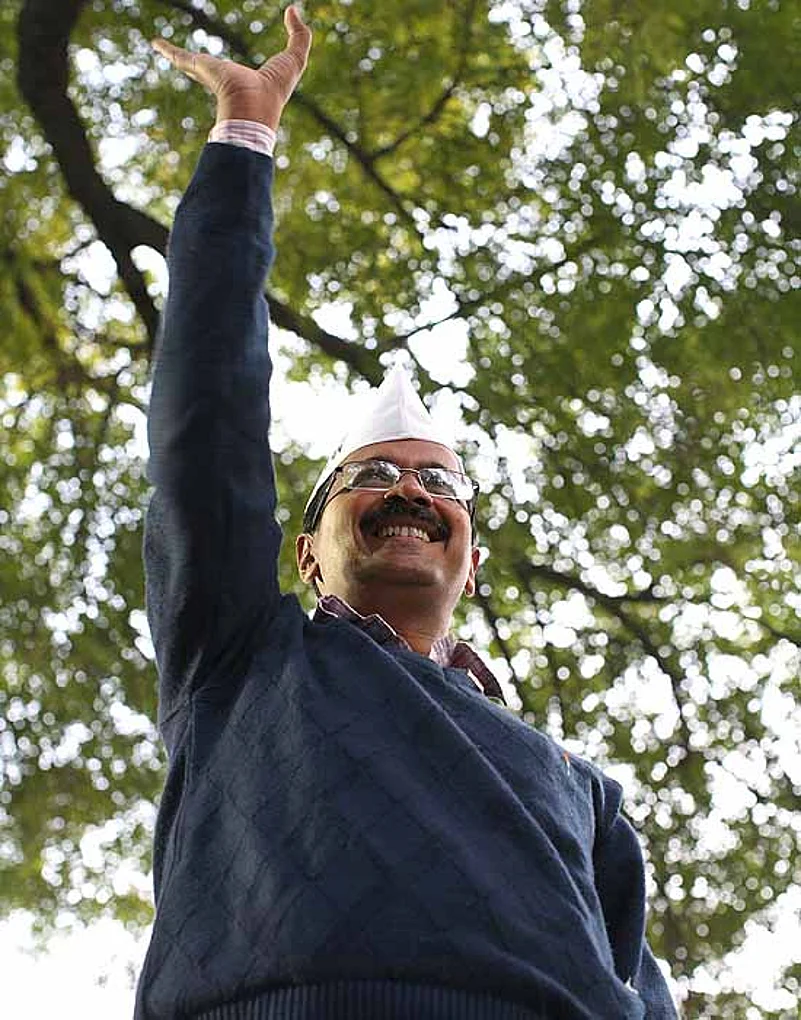

It was amidst this focus on Rahul and Modi that Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) made its spectacular showing in the Delhi elections. However it goes from here, the party has already shown that political change of a kind that even optimistic supporters of Indian democracy would not have predicted is very possible—transparent funding, young candidates with barely an FIR against their name and an organisation of volunteers driven by an enthusiasm for change rather than the promise of patronage.

No stalling Rhetoric is Modi’s strong point, and he is maxing its mileage. (Photograph by Amit Haralkar)

It is no surprise that as this piece is being written, two developments are under way that signal both the strength and weakness of this new paradigm. The first is the passage of the Lokpal Bill by both the Houses of Parliament. This is a clear response to the AAP victory, however much the followers of Anna Hazare may claim credit on behalf of their leader. This bill is in effect the political establishment’s bid to neutralise the AAP threat and defuse the public anger against corruption that has seen the Congress decimated in Delhi and the BJP confounded in its attempt to form a government. Both parties fear a possible carryover to the Lok Sabha elections, however remote the possibility may look now. This fear is why they are so willing to let the credit go to Anna, the very man they had derided just a year earlier, in the hope of containing Kejriwal.

As Anna sat on his umpteenth fast, this time in anticipation of a result he knew well in advance, AAP member Gopal Rai, whose politics lean well left, took on Gen V.K. Singh, a former army chief, whose flirtation with the BJP has hardly been a secret. Seen in context, the faultline wasn’t exactly revelatory. The Anna movement before the AAP came into being was embraced by a wide variety of people. Anna himself was from the right, as were Kiran Bedi and the numerous Sangh elements who hoped to strengthen the moment that was undermining the Congress-led UPA coalition. There were others like Prashant Bhushan, a human rights man with far left touches, and Yogendra Yadav, a liberal, who believed that the movement represented a new kind of politics. When the AAP was born, it was no surprise that the entire spectrum to the right in the movement, including Anna and Kiran Bedi, did not take part. For them the movement was a way to weaken the Congress and pave the way for a Modi-led BJP. The AAP, though it seems to have no true realisation of this fact, is poised as a natural inheritor of the demise of the Congress as the liberal alternative. The same space is available nationally, because the showing of the Congress in Delhi is only a precursor to its showing nationally, but the AAP still seems to lack a full grasp of its own potential and its natural political role.

The enigma at the heart of the AAP, the man who allowed such a disparate set of people to come together in the Anna movement, is Kejriwal. There is something chimerical about the man; in him, people see what they want to. Anna trusted him at one point, and Kiran Bedi, soon after the results in Delhi, declared that the AAP was in safe hands. Both may have changed their views in Ralegan Siddhi recently, but it still is worth asking why many of those on the right in the Anna movement saw him as one of their own.

He has given reason enough for that in the past. He has stood for merit in admissions, usually shorthand for an anti-reservation stance, and had campaigned directly against the Congress during the Hissar Lok Sabha byelections. For those on the political left, his work on the RTI was just one instance of his progressive stance. In this instance, it seems both those on the left and the right had reasons for their beliefs. Kejriwal is a man who is as transparent in his dealings as his party is in its funding, but he seems to lack ideological moorings. He wants to represent change without specifying what that change would be.

Sonia’s dilemma Rahul, pitted against Modi, seems to be getting nowhere. (Photograph by Tribhuvan Tiwari)

This is evident in the platform of the AAP, with its lack of specifics on a host of important issues. It is partly this lack of clarity which left them floundering for days on end with government formation in Delhi, seeking a referendum as if their voters had voted in the hope that the party should not form a government. Unclear on what they really want, they seem to have no way of deciding between the pragmatic aims of governance and the idealistic requirements of the movement they once represented.

However the AAP leaders understand and interpret their role, the fact remains that a vacuum is opening up in national politics with the terminal decline of the Congress. The party has been written off before, but now it seems to lack any means of resuscitation, whether through the non-existent charisma of their first family or through a grassroots revival because the party completely lacks the kind of leaders needed for that.

If the AAP cannot move quickly to occupy this space, or, even as is more likely, it does so in part, a host of regional parties will be the gainers. It is easy to enumerate the major players in this scenario; among the most formidable will be the three women—Amma, Behenji and Didi. They may have various options, but the more-than-likely strong showing by Modi will mean that anyone looking to ally with the BJP will have to be satisfied with a subsidiary role in a coalition. Jayalalitha is the only one likely to try this tack.

If a Modi-led BJP, as is most likely, stops at around 170 seats or so, a churning will start again in the BJP. All those recently eclipsed, including Advani, may see reason to hope again as allies search for someone more acceptable than Modi, but that would be a misreading of the man. Having brought the BJP this close, he is unlikely to step back and let someone else from his party become PM. This effectively confines the BJP to the opposition, where Modi can play to the gallery in Parliament while an unstable alliance collapses in a couple of years.

The real dangers of Modi then could well be delayed, but maybe not by much. Those who worry about his ideology will do well to remember that a greater threat lies in the cult of personality he fosters and his disregard for institutions. The same RSS that is so firmly behind him will one day rue the fact, as they already do in some measure in Gujarat, that they backed him. But that will come later, his first targets, and indeed his first victims, will be those who continue to speak against him, whether in universities, institutions or the media.

The only real alternative to this possibility is an alliance that can miraculously hold together and actually govern effectively. That can occur only if it is glued together either from within or from outside by a party that plays the role the Left did in UPA-I. A stronger Trinamool is unlikely to allow the Left to repeat the feat, but this may well be a possible role for the AAP. Even so, such an alliance will require support from the outside by the Congress. Perhaps, then, the opportunity to form a government in Delhi supported by the Congress seems a forerunner of the tests that lie ahead, and a measure of whether the Congress has forgotten its short-term arrogance of the 1990s that saw it bereft of power for seven years.

Then again, I may well have left out the only scenario that may actually occur. The only thing we can be sure of is that we are living in the midst of the old Jewish curse; politically, these are very interesting times indeed.

(Hartosh Singh Bal is a journalist and the author of Waters Close Over Us: A Journey Along the Narmada.)