I wanted to become a museum curator. For that reason, in the first year of my college, I took up archaeology and museology. But I could not continue further studies as I had to take care of my family after my father developed a serious illness. I was the eldest son. That’s how I landed in the traditional profession of my family — farming.

I started farming on my ancestral farm in Kirugavalu village in Mandya district of Karnataka. Initially, I tried only conventional farming — or chemical farming, as it is called. I did that for three years. We already had three varieties of rice and that inspired us to create a bigger selection of rice varieties. Then, I started to think, why can’t we convert our farm into a live rice museum?

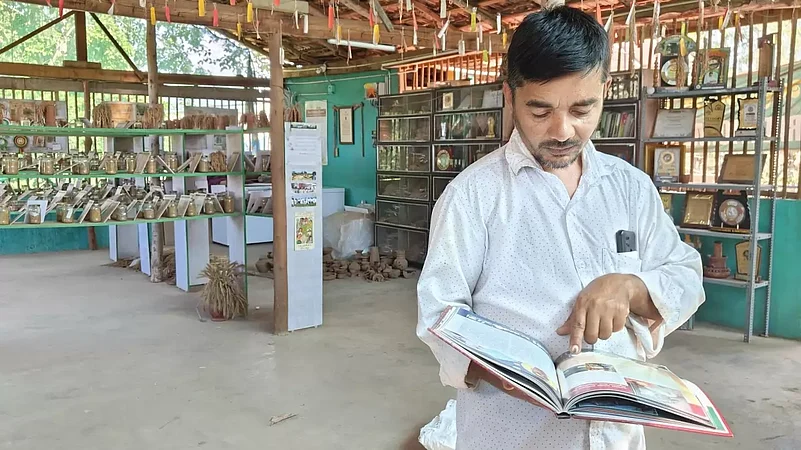

We then started collecting rice seeds from neighbouring villages, then from neighbouring talukas and then districts and finally from across the entire country. I went around the state and then around the nation collecting seeds and growing them, and then distributing it to farmers. We want to conserve the traditional varieties of rice for the future generation because these are existing varieties now. For this, I set up a Rice Diversity Centre. It is set up on the first floor of my house. It is a farmer-initiated non-profit traditional paddy diversity curating and training centre. We aim to conserve paddy diversity and disseminate indigenous wisdom of farmers. Till date, we have conserved 1,350 varieties of paddy.

This includes the Black Jasmine of Thailand, green rice from Odisha, and the Burma Black. We started this in 1996.

We want to conserve these traditional varieties for the future generations. When we talk of rice, we only know about the white rice. We don’t know about the green rice, black rice, or red rice. In our collection, we also have the scented rice, medicinal rice, rainfed rice —which can just grow in the rain— and deep-water varieties.

We are conserving these varieties from Kashmir to Kanyakumari and from Gujarat to Manipur. In 2012, I received the Plant Genome Saviour Farmer Reward and Recognition award from the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India. In 2015, ICAR-Indian Institute of Horticulture Research conferred me with the award of excellence in horticulture. I have received many awards and recognition for my work.

But I have not got the necessary support. If we get government support, we can conserve more varieties.

We want to multiply these varieties and take them to the future generations, spread this knowledge about traditional rice, and analyse their medicinal and nutrient properties. Forty years ago, our food was served as medicine. Today, we are consuming medicine as food. We have also come up with a fine version of black rice which was not available. We plan to get it registered with the National Innovation Foundation in Gujarat and spread it across the country. Everything is grown organically here.

We are also known for conserving and growing mangoes that were cultivated during the time of the ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, who had set up a small watch tower at the site of our village to keep an eye on British forces marching towards Srirangapatna — Tipu’s capital.

One of my ancestors served in the army of Tipu Sultan who donated orchards to his soldiers at Kirugavalu to grow different varieties of mangoes. The 5 km radius was full of mango orchards. This one was called the Bada Bagh. This name is even mentioned in the Gazetteer. When I got custody of the farm, there were 130-135 varieties of mangoes.

My grandmother used to tell us that during their time they needed a mashaal —traditional torch— to enter the orchard because it was so dense. A jungle of mangoes. The mangoes would be sent to Tipu as well as to the Maharaja of Mysore.

Today, around 120 varieties still exist here. Some of the mangoes are unique — mangoes that taste like sweet lime or apple, mangoes shaped like a banana, or scented like jeera. My father would tell me stories that when he was a kid, he could pop 25 mangoes into his mouth at one go — so small was one of the varieties. It’s now extinct.

After the Krishna Raja Sagara Dam came up on the Cauvery, farmers started cutting their mango orchards and began shifting to paddy cultivation to take advantage of the irrigation facilities. My family continued to grow mangoes. We have got our mangoes documented and registered at the National Bureau for Plant Genetics Resources as a national property. It should be a national property. We have records running back as seven generations. Tipu had a lot of interest in this.

My grandmother loved one particular mango. It was called the Amini. She would pluck the mangoes and distribute them among the family and officers. She had great attachment with the tree. During the mango season, she would even spend 10-15 days under that tree. When she died, the mango tree also fell soon after for no reason. Call it attachment?

(As told to Omar Rashid)