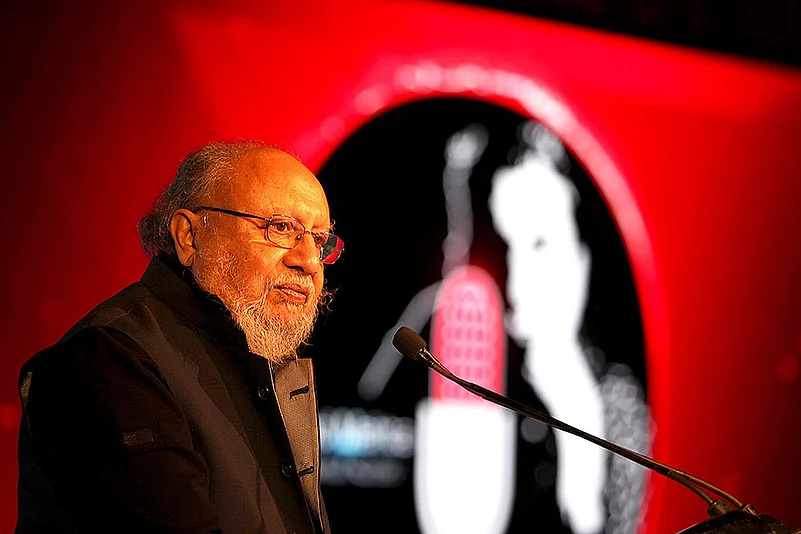

At 80, Ashis Nandy goes to office, his beloved CSDS (Centre for the Study of Developing Societies), thrice a week. He doesn’t take a salary and does not have a pension after he retired from the Centre some 15 years ago. But he likes to interact with the young minds there. The Nandys’ living room is more like a study, bookshelves on all sides, papers and files strewn all over the tables, and a dozen smoking pipes here and there. “Let me light my chillum,” he says. What tobacco is it? “I like Dunhill and Davidoff. I used to like a Trichinopoly brand and get it through a close friend, but he died and I cannot get it anymore. Even these are hard to get as I am cutting down on my international travel,” he says and settles down for a chat. Excerpts from the conversation with Satish Padmanabhan.

Your mother was the first Indian vice-principal of La Martiniere for Girls in Calcutta. It must have been a very academic milieu for you, right from childhood?

I read that in a biographical note on me. But that was the case in most middle-class Bengali families at the time—they gave tremendous importance to learning. We had access to so many libraries, there were so many books at home, it was customary to gift books on birthdays and marriages; it was rarely a dress or a new pair of shoes. There was much pioneering work in many fields taking place in Calcutta those days. It was the 1950s and some of finest writers of Bengal were in their prime; Satyajit Ray had produced his first film and Shambhu Mitra’s theatre group Bahurupee was very active. The colonial period had not been a good time for our educational system; it posed new challenges that opened up new possibilities, but also broke the self-confidence of a large section of the Bengali intelligentsia. The 1950s was the decade when the process of the recovery of the self became noticeable. Bengalis had been under colonial rule the longest, since 1757, and had taken to English literature and modern science quickly. It was not just love for new knowledge, but also the new job opportunities created by the colonial system. By the late 18th century, it was common to see people begging, not for alms, but for English books at Calcutta’s dockyard.

You were studying to be a doctor in Calcutta.…

Yes, I was in the medical college for three years, but I ran away.

From home?

No, from medical education. I went to Nagpur for a vacation to see my aunts, my father’s two unmarried sisters who were then principals of two schools at Nagpur. I told them I didn’t want to study medicine and they took it rather calmly. Unlike my parents, who were very upset and went virtually into depression. It was their life’s ambition to make their son a doctor; they thought it would give me economic security and success in life. There were half-a-dozen doctors in my family and, looking at them, I knew my future right there. And it was a terribly boring future. My parents were not in touch with me for nearly two years, until I completed my BA.

As I was exposed to science and mathematics earlier, it was easy for me to pick up the social sciences, then trying desperately to quantify every social and psychological concept and phenomenon. I also had more time in Nagpur to read whatever I wanted to. The sociology department of Nagpur University was in Hislop College and it was excellent.

This would be soon after Independence. Was the faculty all Indian?

If I remember correctly, when I joined Hislop, there were two non-Indians. By the time I graduated, one of them had gone back.

And after sociology, another big switch, to clinical psychology?

In Nagpur, I was reading a lot of books on psychology. The university library was superb and very accessible. Freud, in English at least, was lucid, though he turned into an ultra-positivist psychiatrist. I would rebel against that later, but at the time it opened a new world for me. So, when the B.M. Institute of Mental Health in Ahmedabad announced research and training fellowships, I applied. This idea of using clinical insights for larger social problems was so fascinating, it changed my life. Psychology had already grown by the mid-’50s. It had expanded during World War II and, by the time I joined B.M. Institute, it was a most attractive discipline.

Disciplines also have their cycles of creativity and popularity. Now, sociology and political science are not in the best of health globally. Nor is anything spectacularly new coming out in disciplines like management and academic psychology. As for development economics, one knows all there is to know. A country can develop without development economists. The entire discipline now is primarily a matter of crossing the t’s and dotting the i’s. It started with community development, then rural development in India and Tanzania and ethno-development in Mexico. Then it became alternative development and now the buzzword is sustainable development. I don’t think this will last either. Whenever countries have developed, they have done so with the old-fashioned concept of Development, with a capital D.

Has psychology too reached a saturation point?

Psychology dominated the show from the 1940s to the ’80s. A lot of creative thinking took place during that time, and now I see a clear decline. There have been major breakthroughs in certain areas because the data were not previously available or were not collected for political reasons. For instance, in genocide studies, but for the European genocide of the 1940s, earlier psychological work was scanty. Many of the genocides have been rediscovered or owned up as genocide only now. Nobody knew much about the Indonesian genocide until Joshua Oppenheimer made a documentary on it in 2012 (The Act of Killing), making the killers, who considered themselves great nationalists, act out their actual role in the genocide. People had almost forgotten the German genocide of Hereros and Namaqua people in South-West Africa (now Namibia) in the early 20th century. They virtually wiped out two entire communities and the perpetrators were very proud of that achievement. Then there was the Nanking massacre by the Japanese during World War II and the old case of the Armenian massacre, which the Turkish government even now doesn’t recognise as genocide. But many Turkish intellectuals think otherwise. This is an example of how a new discipline or subdiscipline is born.

Wasn’t it in Ahmedabad, while studying psychology, that you met your wife?

Yes, she was already in the B.M. Institute, in the clinical side.

So that’s how you speak fluent Gujarati....

Well, I speak it fluently, but not correctly. However, I can read Gujarati.

How many languages are you comfortable in?

I can handle only two languages well, Bengali and English. That too Bengali first and then English. Some things come intuitively to me only in Bengali. I think in Bengali.

I know a little bit of Hindi from my childhood, like everybody did in Calcutta, because about two-thirds of the working population in the city was from eastern UP and Bihar and spoke mostly Bhojpuri or Maithili. But my confidence in Hindi was broken when I went to Nagpur. There is a large settlement of Bengalis in Nagpur and they used to ask, “Where did you learn this mixture of Hindi and Bengali?” For I would say luka liya for chhupa liya and bujha diya for samjha diya. These were perfectly legitimate in Bhojpuri Hindi, but I did not know that. So, I gradually picked up Nagpur Hindi. Then I went to Ahmedabad and some of my colleagues began to ask me, “Yeh mawali Hindi kahan se seekha aapne?”

Though you are a confirmed non-believer now, you were raised as a Christian.

Yes, my parents were devout Christians. But I did not notice much difference between Christian values and the values of our non-Christian neighbours. These differences were reduced even more by the presence of reformist sects like the Brahmo Samaj; Bengali Christians had the same kind of respect for austerity, puritanism, strict morality and, if I may add, primness. I am pretty sure most Bengali Christians will find nothing funny in the cliched story about Heramba Maitra, the famous Brahmo leader known for his high moral standards. One day, when Maitra was standing in front of his house, a passer-by asked him the way to Star Theatre. A hardened puritan convinced that theatres were dens of immorality, the Brahmo leader sharply said he didn’t know. A few moments later, it struck him he had lied and he ran after the pedestrian. On catching up with him, he said, “I lied to you. I know where Star Theatre is, but I won’t tell you.’

But your parents didn’t give you a Christian name?

My father would have claimed that I had a perfectly Christian name. Calling me Benedict would have only changed the language, not the meaning of my name.

It is hard to believe that Pritish Nandy is your brother. You are an academic and an intellectual; he is flamboyant and makes Bollywood films…

He is essentially a poet and a brilliant self-taught designer, though he has many incarnations. Don’t get taken in by what he is doing. I think he produces films and does many other things to keep himself and his family afloat and stable. But his best work is in poetry and perhaps also in designing.

Your politics is also diametrically opposite of his.

That’s true if you take the left-right dichotomy seriously. But he really doesn’t believe in any systematic ideology. I think he, like many of his kind, belongs to a post-ideological generation. It’s true of many politicians too. Ideology for them is a transient instrument. Everyone knows this. That is why they are not surprised when someone changes colours overnight. In Britain, everybody remembered Winston Churchill switching from the Liberals to the Conservatives in 1924. Everybody reminded him of that change as long as he lived, calling him a turncoat. Here, if somebody who has been in the CPI(M) for 30 years and jumps all the way to the BJP, nobody bats an eyelid. Sudheendra Kulkarni was a card-carrying member of the Left. Swapan Dasgupta was a Trotskyite for a good 20-25 years.

I have come to a somewhat similar conclusion about ideology through a different pathway. My work on comparative genocide tells me that ideology arguably has been the greatest killer in mass violence in the 20th century. Religious war might have been so in earlier centuries, but the records of many secular ideologies—nationalism, Leninist and Maoist Marxism—have been much worse in our times. Turncoats, to the extent they have an instrumental view of ideologies, are probably safer.

In The Tao of Cricket, you bring some of these concerns to cricket.

Yes, it is basically a book on political ethics balance. Cricket is like a Rorschach Test—a person reveals himself because nothing much happens on the field. It reveals who really you are and not what you want people to believe about you—at least Test cricket, which is truer to cricket’s original self and is something like the Japanese game of Go. Cricket is a slice of life, or a reflection of a slice of life as it is refracted through the personalities of the players.

Do you still follow cricket?

I follow it, but not that much. But I am still very proud of The Tao of Cricket. It is my favourite book, where through cricket I have coped with the problems of ethics, friendship, enmity, victory, defeat and the fate of homo Luden.

What do you think of this new format of T20 cricket?

That’s not cricket. It conforms to the standard protocol of corporatised sports. One-Day cricket is a bit more nuanced, but T20 is a forgettable enterprise.

You are also very much interested in films. How come you never wrote a book on it?

I am interested in popular cinema. I never wrote a book on films but I edited one (The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence, Culpability and Indian Popular Cinema). The Tao of Cricket, though, has long section that compares popular cinema and cricket as two distinct but compatible modes of self-expression.

There are many things popular cinema did first to survive on people’s acceptance. The more absurd and repetitive the story, the more people seemed to like them and the films became hits. A good example would be the films of Manmohan Desai. Nobody will consider them classics, and yet they captured the heart of a country. Why? If you see the earlier films of Amitabh Bachchan, there is a clear shift. He breaks the mould of the earlier androgynous heroes. But the older films also survived. Then there is something like the story of Devdas. I once counted about 29 film versions of Devdas. There are three Hindi versions, a fourth silent one and a Bangladeshi version. There have been at least four Telugu versions. Why is a passive, androgynous hero who self-destructs through alcoholism so popular? Why do millions empathise with him? I do offer a partial answer in my long chapter on Pramathesh Barua in my book, An Ambiguous Journey to the City: The Village and Other Odd Ruins of the Self in the Indian Imagination.