Indian Worries

- Will Madhav’s government survive?

- If it falls, the Maoists could return to power

- This could see Nepal move closer to China

- India realises that Maoists must be part of the solution. Therefore...

- Create space for both Maoists and others to work together and ensure a new Constitution is framed by mid-2010

***

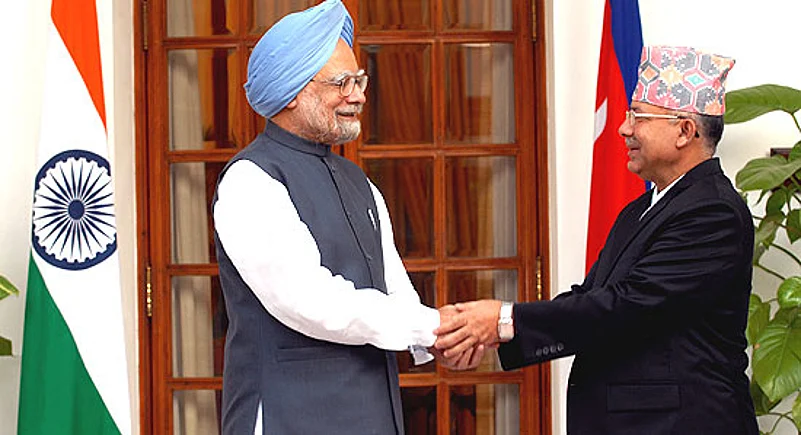

When Nepali Prime Minister Madhav Nepal arrived in Delhi on August 18, he had quite consciously restored the hallowed tradition his predecessor, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’, had suddenly violated—for, a new Nepali prime minister always chooses India as his first foreign port of call. Prachanda, on becoming PM in 2008, had instead bestowed this favour on China, ringing alarm bells in New Delhi about his intention to cosy up to Beijing. The restoration of this tradition, however, has a subtext: Madhav’s visit demonstrates his wish to seek New Delhi’s support in keeping his three-month-old coalition government afloat.

His India visit comes even as political instability continues to buffet Kathmandu. For one, Madhav wouldn’t have become PM had Prachanda not decided to unilaterally dismiss the army chief Rookmangad Katawal, who was bitterly opposed to the integration of Maoist fighting cadres into the army. The other political formations ganged up against Prachanda’s precipitous decision, compelling him to resign. Weeks of instability saw Madhav muster together a coalition. His grip on power, though, remains tenuous: a day before he flew down to Delhi, the Maoists made it clear at an all-party meeting that he must not sign major agreements with India. Worse, foreign minister Sujata Koirala, a key member of the Nepali Congress, Madhav’s key coalition partner, dropped out of the visit, piqued that she hadn’t been made deputy prime minister.

As Madhav met Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, there were many who were asking: can India bolster the new government in Kathmandu? Former Indian ambassador to Kathmandu K.V. Rajan told Outlook, “I’m afraid we have lost the plot in Nepal. India seems to have tied itself in knots.” He feels India’s problem stems from the erroneous assumptions it made when it brought together the Maoists and other democratic forces to marginalise King Gyanendra. Defying Delhi’s predictions, the Maoists emerged as the biggest winner in the election and Prachanda became PM. Extremely uncomfortable with Prachanda and his flirtation with Beijing, New Delhi wanted to see the end of Maoist rule. This was successfully achieved over the Katawal incident.

Maoist protests post Prachanda’s expulsion

Others say India didn’t make wrong assumptions in midwifing an agreement between the Maoists and mainstream political parties. It was only when Gyanendra began to overreach himself, infuriating non-Maoist parties as well as the people, that New Delhi began to seriously look at a scenario in Nepal beyond the monarchy. After all, New Delhi did not want to be popularly perceived in Nepal as the force bolstering the much-detested Gyanendra. It’s true India did not think the Maoists would emerge the largest party in the Constituent Assembly elections of April 2008, vanquishing by a substantial margin the Nepali Congress and the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist).

Nor did Prachanda provide any comfort to New Delhi. His decision to visit Beijing in August 2008 only deepened India’s suspicion. In his years in the bush, the Maoists had constantly railed against India and its inclination to ‘interfere’ in Nepal. Prachanda’s China card was consequently seen as a deliberate provocation. Yet Nepal’s importance in India’s scheme prompted New Delhi to allow Prachanda an official visit in September. This was hailed as a success, but India looked askance at Prachanda’s attempt to dominate the other political parties and his allies in the government.

The Katawal incident only fanned these fears. Prachanda’s decision to sack Katawal was perceived as an attempt by the Maoists to push its erstwhile fighters into the army, capture the institution, and exploit its clout to usher in a one-party system. The Nepali president used his constitutional powers to overrule Prachanda and Madhav’s CPN(UML) decided to withdraw its support from the Maoist-led coalition, forcing Prachanda to step down.

But all this sowed the seeds of discord for the future. Most feel the crisis over the Katawal incident was orchestrated by India, a claim not contested by the Indian leadership either. “It was a very difficult situation for us but we managed to deal quite effectively with it,” an aide of the Indian prime minister said. He offered two reasons to explain Prachanda’s brinkmanship. One, he thought the sacking of the army chief would go unnoticed in India since it was preoccupied with its own elections. Two, he banked upon the Chinese to bail him out. “On both counts, he was totally wrong. India decided to get other political parties to rally against the move. And the Chinese decided to stay away from the crisis,” the prime ministerial aide added.

Obviously, India couldn’t intervene overtly, but it made sure the “middle ground” held, ensuring neither the Maoists nor supporters of the ousted monarch dominated the political scene. An Indian diplomat, who served in Nepal during the Katawal crisis, argued it was not in New Delhi’s interest to see the marginalisation of the Nepali army. “We don’t want the army to get involved in the political mix in the country. We want the army to ensure all other institutions remain in place,” he said. In other words, the army must be there as a counterpoise to the Maoist dream of establishing a single-party political system.

Yet New Delhi wanted to be seen as playing fair. In ensuring Katawal retired at the end of his tenure in July, South Block officials say they sent out a strong signal that India’s only interest was a politically stable Nepal. Former foreign secretary Lalit Mansingh told Outlook, “Nepal is going through an internal crisis and India, which has a large stake there, will have to show patience in dealing with it.” The patience is required because India can’t intervene overtly in another country. Mansingh says India hasn’t lost the plot in Nepal, bolstering his assertion through an example—even though Prachanda lashes out against India, he has asked CPI(M) leader Sitaram Yechury to come to Kathmandu to break the current impasse. “This clearly shows no matter what, Indian help is sought by all in Nepal,” Mansingh concludes.

New Delhi is in no mood to see a drift in the situation in Nepal. No wonder Manmohan Singh’s meeting with Madhav had the most important Indian cabinet ministers (finance, home, commerce, foreign and power) in attendance. A trade agreement and financial assistance to Nepal are on the anvil. But will this ensure Madhav’s survival? With the Maoists not willing to play ball, should other partners of the government, like Sujata Koirala, begin to demand their pound of flesh, fresh doubts will be raised about the durability of the peace process and the Constituent Assembly’s ability to deliver a new Constitution by mid-2010. The ensuing political instability could only strengthen the Maoists, much to India’s discomfort.