Seven decades have passed since the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. This victory, etched in American history classrooms, promised a future where children of all backgrounds would learn together in integrated environments. However, the reality on the ground paints a different picture. American schools are becoming increasingly segregated, raising critical questions about the legacy of Brown v. Board and the path forward towards achieving equal educational opportunity.

The Legacy of Segregation

Despite the legal victory in 1954, the dismantling of segregation proved a far more arduous task. Decades of resistance and legal challenges followed, hindering the full implementation of Brown's mandate. Southern states, in particular, employed a variety of tactics to delay or obstruct desegregation efforts. These tactics included school closures, the creation of segregated private academies, and even violence. The slow pace of change underscored the deeply entrenched nature of racial prejudice in American society.

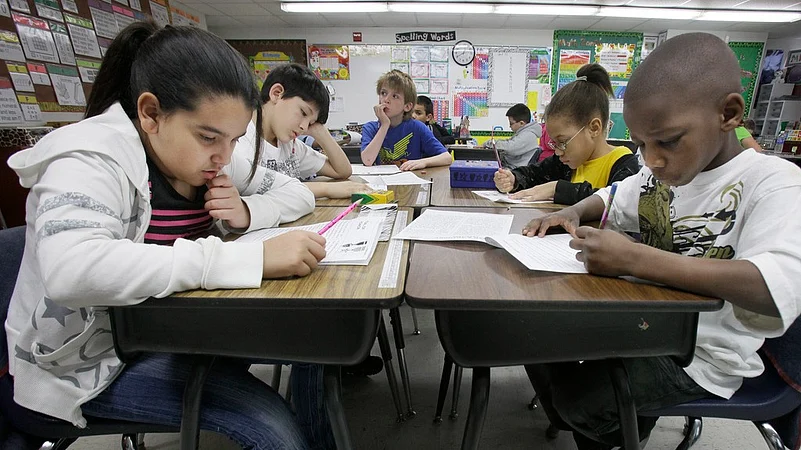

Today, a troubling trend of re-segregation plagues American education. Schools serving low-income communities, which are often predominantly Black and Hispanic, face a stark reality. These schools are more likely to be under-resourced and lack access to the same quality of programs and facilities as their wealthier counterparts. Classrooms may be overcrowded, with fewer experienced teachers and counselors.

Advanced Placement (AP) courses and extracurricular activities may be scarce. This socioeconomic disparity creates a vicious cycle, reinforcing racial segregation and perpetuating educational inequalities. Students attending segregated schools are often denied the same opportunities and resources as their peers in wealthier districts, hindering their academic achievement and limiting their future prospects.

Why Integration Matters?

The importance of integration extends far beyond superficial notions of diversity. At its core, Brown v. Board was about ensuring equal opportunity for all children. Integrated schools provide students of color with access to better resources, higher quality instruction, and a broader range of educational experiences.

They are exposed to different perspectives and cultures, fostering understanding and tolerance. Research consistently demonstrates the positive impact of integration on academic achievement, graduation rates, future career prospects, and even health outcomes. Students who attend integrated schools fare better across a multitude of metrics, regardless of their own racial background. Studies have shown that students of color in integrated schools experience higher test scores, increased enrollment in advanced coursework, and a greater likelihood of attending college.

Conversely, segregation concentrates poverty and disadvantages students of color, limiting their potential and undermining the promise of a truly equitable education system.

Progress and Setbacks in Integration Efforts

The history of school integration in America is marked by both progress and setbacks. Busing programs, a key strategy employed in the decades following Brown, aimed to desegregate schools by transporting students to schools outside their neighborhoods. While these programs achieved some success in bringing students of different races together, they also faced intense resistance from white communities.

Many white parents objected to their children being bused to predominantly Black schools, fearing a decline in educational quality or exposure to violence. These concerns, often fueled by racial prejudice, led to white flight from urban school districts, further deepening the racial divide. Furthermore, court rulings since the 1970s have progressively limited the tools available to school districts for achieving integration. The landmark Milliken v. Bradley decision in 1974, for example, restricted the use of busing across district lines, hindering efforts to integrate suburban schools with those in urban areas.

The burden of ensuring racial diversity has shifted to individual families, often with mixed results. Magnet schools and inter-district transfers can offer some avenues for escaping segregated schools, but these options are frequently limited and leave many students behind. Magnet schools may have rigorous application processes, and inter-district transfers may be restricted by availability or transportation challenges.

These limitations highlight the need for systemic solutions that address the root causes of school segregation.

Legal Challenges and New Strategies

Despite the challenges, the fight for school integration continues. Organizations like Brown's Promise are working to bridge the gap between school funding and integration. Their strategy leverages state courts to secure the tools that have been taken away from school districts by federal rulings. Brown's Promise argues that unequal funding between predominantly white and minority schools violates state constitutions, pushing for greater investment in schools serving low-income communities.

Recent lawsuits in states like Connecticut, Minnesota, and New Jersey demonstrate ongoing efforts to achieve school integration through legal means. These initiatives aim to challenge funding disparities and promote policies that encourage racial diversity within schools, such as magnet school programs with open enrollment or controlled enrollment plans that take into account racial demographics.

The path towards a truly integrated educational system is imperfect and likely to face roadblocks. However, the potential benefits are undeniable. By ensuring equal access to quality education for all students, regardless of race or socioeconomic background, America can invest in its future and build a stronger, more just society.

Several challenges remain on the road to achieving integration. One major hurdle is the issue of residential segregation. Since schools are typically funded by local property taxes, schools in wealthy neighborhoods tend to have more resources than those in low-income areas. This funding disparity perpetuates the cycle of segregation, as families with means often choose to live in communities with better schools. Addressing residential segregation will require comprehensive strategies that promote affordable housing options and mixed-income communities.

Another challenge lies in overcoming racial prejudice. While attitudes towards race have undoubtedly improved since the Brown v. Board era, implicit biases can still influence decision-making processes, such as school enrollment or teacher placement. Professional development programs for educators that address racial bias and promote culturally responsive teaching practices are essential steps forward.

Despite the challenges, there are also opportunities to advance the cause of integration. One promising approach is the use of interdistrict choice programs. These programs allow students to attend schools outside of their immediate neighborhoods, fostering racial and socioeconomic diversity. However, interdistrict choice programs must be carefully designed to avoid exacerbating existing inequalities. Transportation options and clear guidelines for admissions are crucial to ensure equitable access for all students.

Community engagement is another key factor in achieving integration. Building partnerships between schools, families, and community organizations can foster a shared commitment to diversity and equity. When parents and community members are involved in decision-making processes, they can help shape policies that promote integration and ensure that all students have the opportunity to succeed.