Jordan became the first country in the world in 2024 to be officially verified by the World Health Organization (WHO) for eliminating leprosy, even as several countries, including India, continue to struggle with the disease that has persisted for decades.

“Making leprosy a notifiable disease was key to Jordan’s success, ensuring timely diagnosis and prompt treatment,” said Dr. Catharina Boehme, Officer-in-Charge, WHO South-East Asia, as the world marked World Leprosy Day on January 25.

In contrast, India has seen only a gradual decline in new leprosy cases. According to WHO data for 2024, Brazil, India, and Indonesia continue to report more than 10,000 new cases annually. India has now set a target to eliminate leprosy by 2027—three years ahead of the WHO’s global goal—following its decision to declare the disease notifiable in May last year to strengthen surveillance and early detection.

Leprosy is reported from all the six WHO regions; the majority of annual new case detections are from the South-East Asia Region, which includes India.

Dr. Boehme also noted that the introduction of multi-drug therapy (MDT) in the SEARO region has been a game changer, while early interventions such as contact screening now make disability prevention possible through timely detection.

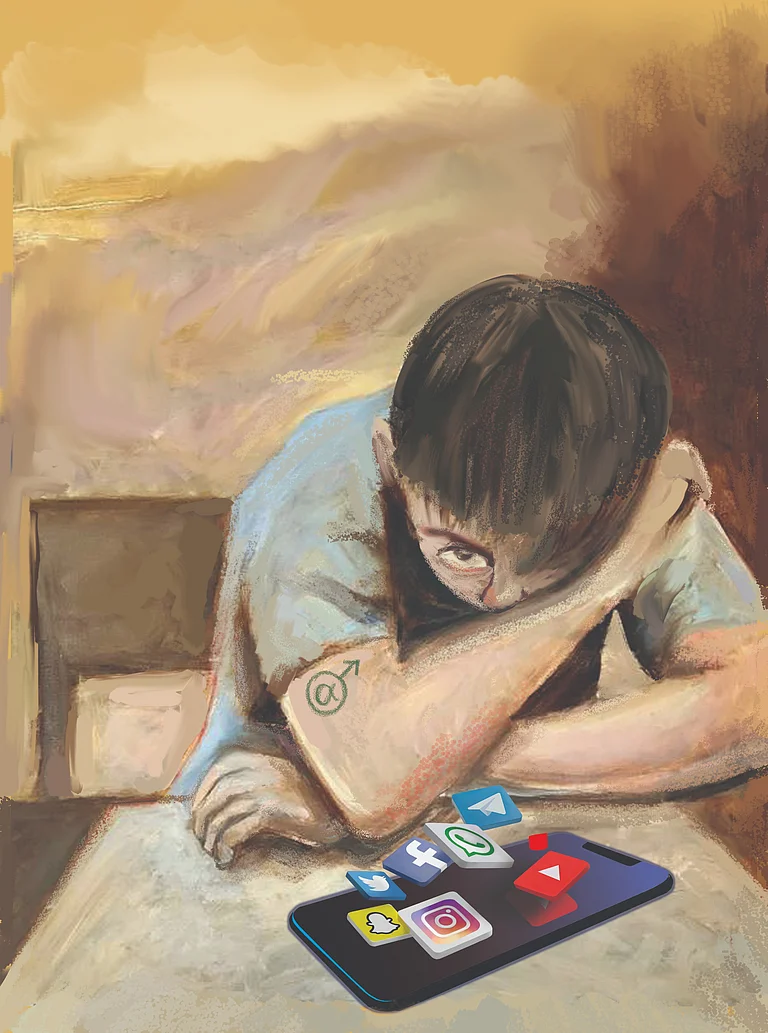

“Yet, despite these medical and technological advances, the social dimension of leprosy remains largely neglected. Stigma and discrimination continue to deter people from seeking timely care and adhering to treatment. The impact extends beyond those affected by the disease to their families, fostering social isolation, marginalisation and profound mental health challenges,” pointed out Boehme.

She lamented that discriminatory laws still persist in several countries, denying people affected by leprosy their basic rights to employment, education, marriage, and full participation in society.

“Preventive strategies are also being scaled up globally, supported by donors, with single-dose rifampicin being used as post-exposure prophylaxis for those at risk.

“Technology has further strengthened the fight against the disease. Digital tools, including DHIS2-based platforms, are improving epidemiological surveillance and individual case management, enabling data-driven programmatic decisions and more effective care and support for patients,” she pointed out.

While the medical burden is diminishing, the social consequence of leprosy remains unacceptably high, denying people dignity, opportunity, and fundamental rights, she said in a statement here.

While Brazil, India, and Indonesia continue to report more than 10,000 new cases, 12 other countries (Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Philippines, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and the United Republic of Tanzania) each reported 1,000–10,000 new cases. Fifty-five countries reported 0 cases and 117 reported fewer than 1,000 new cases, as per WHO data of 2024.

In India, though a few states had already notified the diseases, the Centre’s move to announce notifiable aims to bridge longstanding gaps in surveillance and inter-sectoral coordination under the National Leprosy Eradication Programme (NLEP), particularly with respect to cases treated in the private sector, which often go unreported.

While announcing the government’s decision last year, Dr. Sunil V. Gitte, Deputy Director General (Leprosy), Union Health Ministry, noted that a key challenge under NLEP has been the lack of coordination with private healthcare providers, which hampers real-time data on the disease burden and delays timely public health response. India has kept 2027 as an elimination target.

Welcoming the move, international NGO Lepra, which works on leprosy and neglected tropical diseases, called it “a proactive and transparent step” that will enhance access to treatment and allow more focused awareness and outreach efforts.

India declared the elimination of leprosy as a public health problem in 2005, having reached a prevalence rate below 1 case per 10,000 population. However, the government acknowledges that transmission continues in certain pockets, especially among tribal and hard-to-reach populations. Dr. Gitte, who has spearheaded several GIS-based innovations in tribal belts of Central India, stressed that the inclusion of leprosy in the list of notifiable diseases is key to achieving sub-national elimination.

Talking to Health Outlook, Dr. Rashmi Sarkar, Director Professor, Department of Dermatology, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Associated SSK and Kalawati Saran Hospitals, Delhi, said that the theme for this year—“Leprosy is curable, the real challenge is stigma”—highlights the urgent need to address social barriers surrounding the disease.

She stressed that it is crucial for organisations to educate patients and communities that leprosy is completely treatable with medicines that are available free of cost at government hospitals and dispensaries. Timely treatment, she explained, not only cures the disease but also prevents complications and deformities associated with leprosy.

Dr. Sarkar emphasised that professional bodies such as the Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists (IADVL) and the Indian Association of Leprologists (IAL) must prioritise education, awareness, and rehabilitation. This, she said, is essential to ensure that persons affected by leprosy do not lose their livelihoods, that children continue to attend school, and that patients are not ostracised by their families or communities.

Highlighting the way forward, she said that sustained messaging on early diagnosis, proper medication, and the fact that leprosy is curable is the most important strategy at this stage. Dr. Sarkar is also Regional Director of International League of Dermatological Societies for South Asia, Middle East, Africa and the Past Director of International society of Dermatology.

Leprosy primarily affects the skin, peripheral nerves, mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, and eyes. While not highly contagious, it can spread through prolonged, close contact with untreated individuals, especially via nasal droplets. Children remain more susceptible to infection than adults.