In June 2021, as the pandemic forced the world into virtual mode, as WhatsApp, Snapchat, TikTok and Instagram became our interface not just for human interactions but also for knowledge and information sharing, I gave birth to a beautiful boy. When I held my baby in my arms, I whispered, “I have no idea, absolutely no idea about how to raise you. About how to be the parent you deserve.” You see, I come from a family of girls. We are two sisters, my mom also has only sisters, and my sister too has only daughters. As a girl born and raised in patriarchal India, and as a journalist turned gender-rights activist, I knew what to tell my daughter. I knew how to prepare her to take on a sexist and misogynistic world. But a son! Those three letters were unknown territory to me.

Fast forward to March 2025, and I found myself gripped with that same fear, rather exponentially, as I sat watching the Netflix series Adolescence. As Jamie sat shaking and crying in the police van, asking for his dad, I imagined my son there. When the polite and shy 13-year-old suddenly changed character and shouted at his therapist in a burst of rage, I tensed up. My son is only about three now. But on a daily basis, he interacts with a world that tells him he has privilege because he is a male. And this signals to him that his emotions should be suppressed because “strong boys don’t cry”, which creates a false sense of entitlement in him with the message—“you can grab what you want without consent”. I worried about my baby boy. When he chose a pink yoga mat at gymnastics, he was told, “Arrey yeh toh ladkiyan use karti hai...tu toh ladka hai” (Girls use this...You are a boy). When he wore a bindi, he was asked, “Arrey, ab chudiyan bhi pehnoge kya?” (Will you wear bangles too?)

The toxic masculinity that my little boy was being subjected to pushed me to think in a very different direction than what my default was—both on a personal and a professional front. Now, I was not just thinking about how to empower girls to believe in themselves but also how boys can be told that they are perfect as they are without having to prove anything. How can we create a system where children grow up knowing and respecting other genders without fear, threat or prejudice? My team and I at The sex education Azadi Project got together to brainstorm and research.

Sex Education

A quick internet search revealed that in the last decade or so many states in India have rejected sex education in their curriculum, labelling it a western concept. Very few organisations have been able to break through the government bureaucracy to include conversations about consent, puberty, gender stereotypes and sex in school curriculums. So, conversations about sex, consent, bodily autonomy are not happening in a sensitive and controlled educational environment that is led by a trained expert. In its absence, tweens, teens and young men are being drawn to online influences—be it pornography or social media chat groups which are uncontrolled, not led by a trained expert, and are at risk of being toxic and violent.

A 2023 study by the Population Council examined the link between exposure to pornographic content among Indian adolescents and violence. According to the study, approximately 88 per cent porn scenes include acts of physical aggression, 48 per cent contain verbal aggression, and 94 per cent of the target group is women. Porn videos also portray men as being in charge, while women are depicted as submissive and obedient. This exemplifies unequal power relations and fosters beliefs of male superiority and women’s inferiority.

How does one responsibly counter this narrative?

The Azadi Project

We at The Azadi Project worked with experts and organisations to draft a curriculum that starts for children as young as seven or eight years. Topics such as consent, boundaries, gender identity and masculinity are taught through play-based interactive sessions facilitated by a trained expert. Three separate curriculums have been designed to meet the age-sensitive needs of the children and young adults—one for children of 3rd to 5th grade, the other two for 6th to 8th grade and 9th to 12th grade. Children are presented with real-life situations/case studies; nudging them to think, question and act. This excerpt from the section on healthy relationship-building is an example:

Meena and Raj are close friends, but Raj often pressures Meena to share her social media passwords, saying things like, “If you’re really my friend, you should trust me and give me your passwords.” Meena feels uncomfortable and invaded but is afraid to say no because she doesn’t want to upset Raj. Despite her discomfort, she eventually gives in to Raj’s demands, which makes her feel violated and disrespected.

Question:

Do Meena and Raj have a healthy relationship?

This curriculum or others like this is no magic bullet that will instantly solve India’s problems of sexual violence and misogyny. But by openly having conversations about our bodies, sex and relationships, we aim to create a respectful way of seeing and addressing each other. Also, the aim is to teach them young, at a critical time in a child’s life, when ideas about gender are taking shape. At this stage, children can develop a gender-sensitive attitude that focuses on equality and equity, instead of a discriminatory approach to other genders. Biased attitudes hinder both personal and national progress. Hence intervention is critical, especially at a pre-adolescent and adolescent stage.

Counter to influencer Andrew Tate’s manosphere philosophy that perpetuates “absolute misogyny and sexism”, we focus on four key modus operandi: create safe and inclusive spaces in schools where children can share their gender-related experiences openly and learn to question gender stereotypes; transform children and young adults into gender champions; increase gender-inclusive practices in educational institutes and communities—for example, inclusive language usage, participation in school and extracurricular activities, also in leadership roles; and promote empathy and respect for individuals of diverse gender and identities.

Since our approach is collaborative and movement-building, the curriculum is open source and free for all. The children at a government school in Delhi, where we have been piloting the programme since last year, are already showing remarkable progress. They feel more confident to talk about their gender-specific experiences such as puberty in shared safe spaces. They also feel comfortable seeking help and support from friends of other genders.

On the home front, this anxious mom is not so anxious anymore. I have found a wonderful way of engaging my three-year-old in important conversations of body, consent and boundaries—PLAY. At three-and-a-half years, we have already had conversations about good touch and bad touch, the importance of respecting ‘no’, and anatomy: the difference in male and female bodies. In order to avoid losing our children to the likes of Andrew Tate and his bhakts, we need to act soon by creating safe spaces at schools and homes, where respectful, open and frank conversations can happen without judgement.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Priyali Sur is the founder and executive director of the Azadi Project that works for women from marginalised and refugee communities

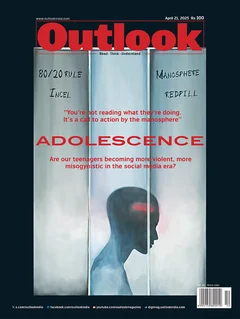

This article is part of Outlook’s April 21, 2025 issue 'Adolescence' which looks at the forces shaping teenage boys today—online misogyny, incel forums, bullying, and the chaos of the manosphere. It appeared in print as 'Boys Can Cry.'