‘MBA’ With A difference

- Set to begin in 2010, the Centre for the Study of Informal Business will focus on the unorganised sector

- Will offer an MA in informal business and target research

- Those against the centre say it’s against the ethos of the left-leaning campus

- Those in favour say the centre must have links with SMES

***

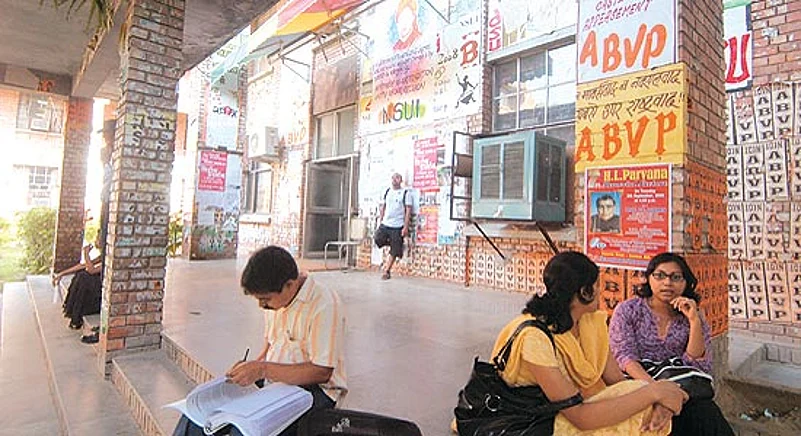

It’s a university where Dow Chemicals is mentioned only when protesting students decry the “unethical” behaviour of US firms. It’s also the kind of campus where Olive Ridley turtles and Singur inevitably dominate talk about the Tata group. With strong political views and an anti-establishment ethos, the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) is not just any left-leaning institution. It’s the academic bastion of the anti-big business viewpoint.

So when there’s talk of setting up a business school at JNU, one can’t help wonder—is there an ideological switch afoot? Not quite, it turns out. The ideological switch, on the contrary, is for the B-school to make. Unlike most existing business schools that train managers for top firms, the Centre for Study of Informal Business, planned for 2010, will only focus on the informal and unorganised sector that employs over 90 per cent of the workforce in India.

This, as JNU vice-chancellor B.B. Bhattacharya explains, is a sector that has failed to catch the attention of most B-schools. “B-schools focus largely on case studies of IBM and General Motors. They have not made much of a mark in conducting research on Indian businesses and producing indigenous literature,” says he. This when Indian corporates are run in a manner distinctly different from those in the West and tend to be controlled by families. “Here you have a situation where a country’s major decisions are going to be taken on the basis of the outcome of a fight within a (business) family. On the other hand, Bill Gates quietly passes on his mantle to a professional, not his son,” he adds.

Given the emphasis on research at JNU, this centre will begin with a research programme and then move on to an MA degree. It has already received sanction for five faculty positions from the University Grants Commission. The centre, beginning 2010, will commence an M.Phil programme in informal business. The research carried out under this programme will then help set a template and evolve a curriculum the master’s programme could follow. Students will be expected to study how informal businesses are run, what unique models they follow and how they fund their expansion, and other allied issues. The entire plan will be put to the university’s academic council for approval later this year.

Bhattacharya sees graduates of this centre joining the government as advisors, working with institutions and NGOs and being employed with firms that are increasingly reaching out to rural consumers. Giving an example of how the students could contribute, he points to debate over the future of small retailers. “We have to have a better idea of the small players in this business. That is where our students will hopefully help.”

Predictably, representatives of small and medium industries (SMES) are eager to see the results of such a programme. Says secretary general of the Federation of Indian Small and Medium Industries, Anil Bharadwaj, “There is no structured research on this sector—hopefully this centre will give a great impetus in orienting research towards SMES, which is a black hole at the moment.” Also, many firms—small as well as large—are looking forward to an increase in the number of ‘hands-on managers’ to help them expand in rural areas. This demand hasn’t been met by the existing business schools given, as Bharadwaj puts it, the “disconnect” with SMES.

But all is not quiet over plans to introduce this centre as some see it as an assault on the fundamental character of the university. “This was meant to be a university with a difference. Never were there plans for any professional school. If we have one for business, what stops people from asking for more such centres on law, medicine and engineering,” asks Kamal Mitra Chenoy, a professor at the university and a member of its executive council that will soon debate whether JNU needs such a centre.

On the other hand, there are some who endorse the idea. “I’m in favour of a hundred flowers. I think it is a good idea to have business schools located in universities that would allow students to take varied programmes and be more socially oriented,” says Jayati Ghosh, professor of economics at the university.

However, even those who approve of this idea have words of caution for the centre. Bibek Debroy, professor at the Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research, says for such a centre to have any credibility, it must have links with the SMES that go beyond research and traditional academics. “I am sceptical of JNU developing any links with industry. Traditionally that has not been the case,” he says. There is, of course, a business angle, he feels. “Because business schools bring a decent revenue stream, I think it is more of a subterfuge, an attempt to bring in a B-school by a sleight of hand. Any conventional B-school at JNU will have the Left up in arms.”

And this is not the first time attempts are being made to introduce SMES in a business school curriculum. Bakul Dholakia, former director of IIM Ahmedabad, says they were included way back in the 1980s but several programmes “petered out” because of lack of popularity. “Research is only the first step in managing these under-managed sectors. The ultimate objective has to be to turn out products that will ensure a flow of skilled manpower to the SMES that require it,” he adds. This can only happen if the centre remains in close contact with the constantly evolving SMES and makes sustained efforts to develop “contextual course material”.

There is no denying the need for such a centre. As Dholakia says, “Among the Indian youth, there are some who want to contribute to society. They have a hazy idea of what to do but no clear focus. Centres like these can attract the few idealistic brains and channelise their energies.” We’ll know by 2010 if the centre will come up—but only in the long run will we know if it’ll succeed.