India Slow Down Story

In May, manufacturing witnessed a lower growth compared to the same month last year

IIP estimates for April this year were scaled down by over 1%, and those for May were lower than last year

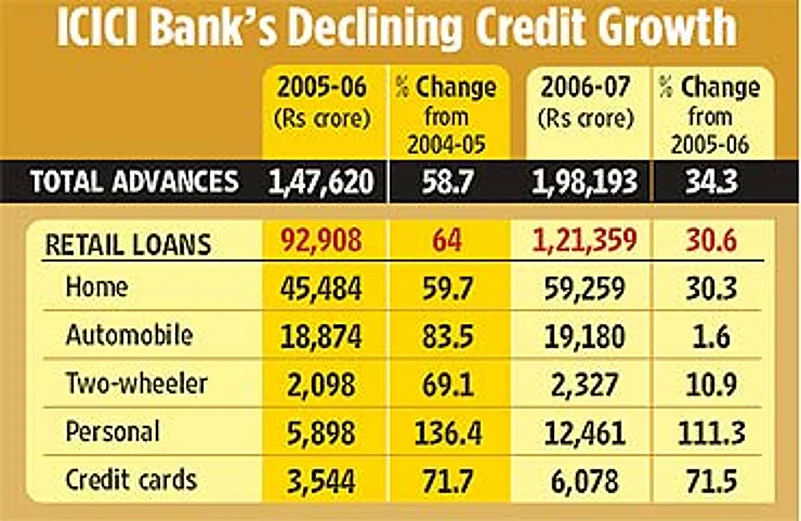

Credit offtake has shown lower growth; in some sectors, the growth has halved

Exports are slowing down; some estimates indicate India will clock $135-140 bn this year, and not $160 bn

Investments, both public and private, are being reworked; in areas like power, it will lead to higher tariffs

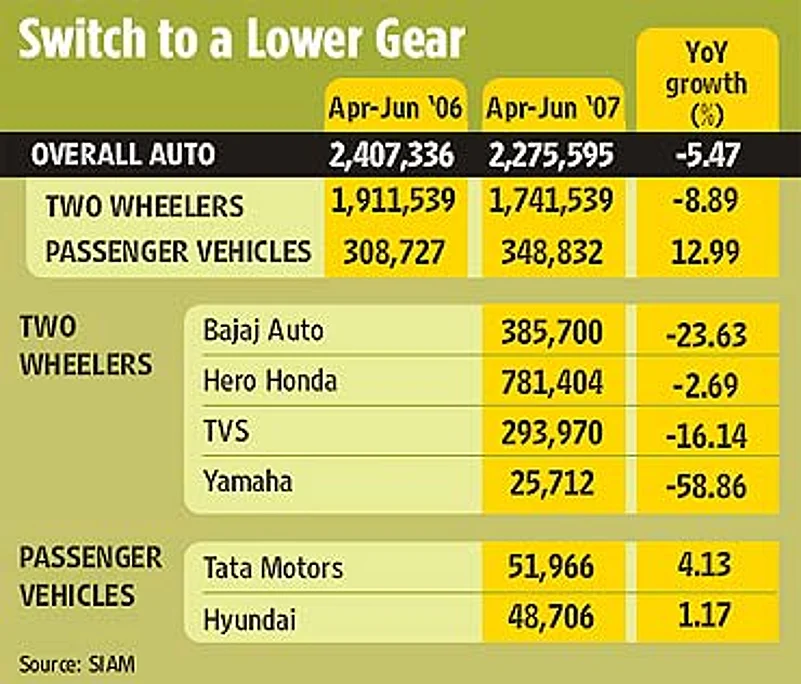

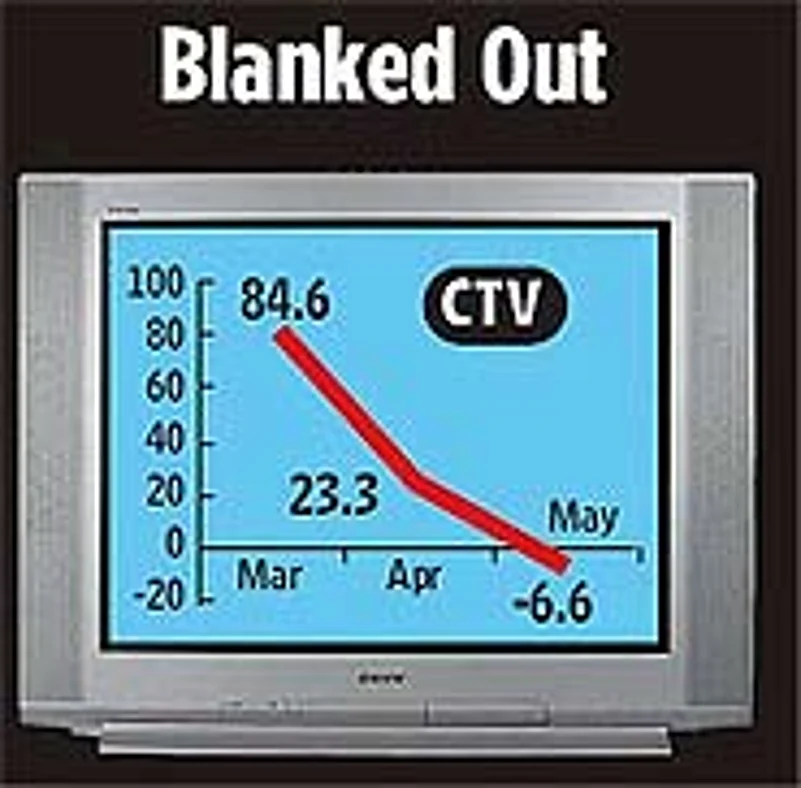

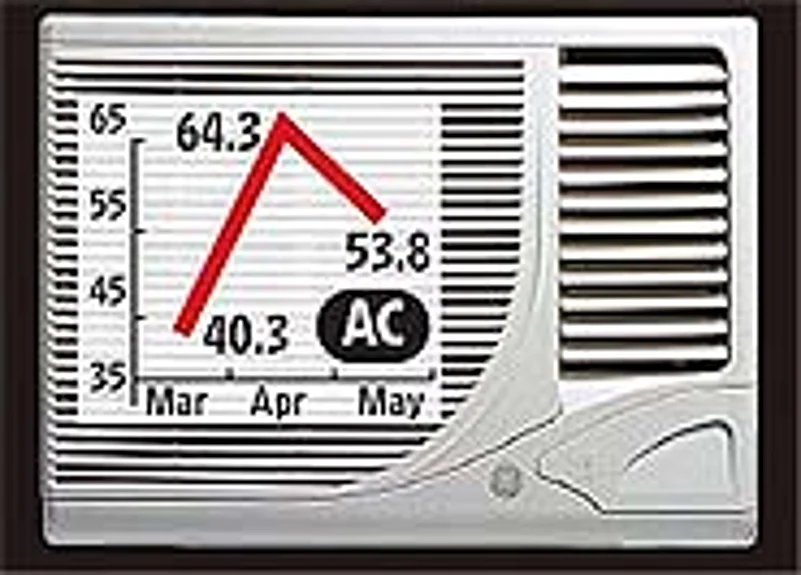

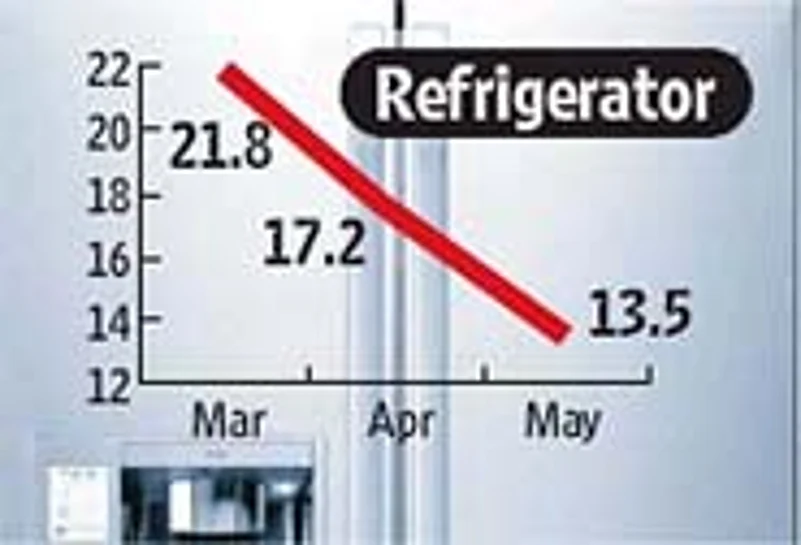

Some sectors like auto and consumer durables are showing signs of much lower growth rates; but firms are still quite optimistic

So, while GDP is expected to grow at around 7.9-9.2% this fiscal, compared to 9.4% last year, the growth is expected to be far lower

***

P. Chidambaram, FM: "In April and May this year, the core industry has done better than in April and May last year."

Y.V. Reddy, RBI governor "We expect the real GDP growth in 2007-08 to be around 8.5 per cent.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman, Planning Commission: "Yes, there will be a moderation in the pace at which the Indian economy has been growing."

Gopal K. Pillai, Commerce Secretary: "In the second quarter, expect some hit (on exports), as witnessed in the first quarter. In September, we will take a review."

C. Rangarajan, chairman, Economic Advisory Council: "There is some slight slowing down of the economy—from 9.4 to 9—if you wish to call it slowing down."

Subir Gokarn, chief economist, CRISIL: "I wouldn't call this economic scenario a slowdown but would see it more as a moderation where an 8.5-9% growth is neither a shock nor a bad omen."

D.H. Pai Panandikar, RPG Foundation: "Even the PM's Economic Advisory Council has scaled down the expectations of exports growth this year from 21 to 18 per cent."

Abheek Barua, chief economist, HDFC Bank: "There is some deflation in the euphoria about the economy but it is certainly not significant. Yes, there is some deceleration."

***

It was quite a surprise. Not many in the government want to talk about it. With his typical slight smile, finance minister P. Chidambaram says that "I don’t wish to comment on it." Another senior bureaucrat was more revealing. "I am sorry that I can not comment on the issues. As a government representative, we have been told to observe a cool period," he says. The head of a leading infrastructure investment firm, which deals with the Centre on a daily basis, too refused to say anything. Question: is the government deliberately trying to douse an economy on fire?

Now, when government officials shy away from certain questions, you can be sure there is something brewing in the corridors of power. It can be a policy-related strategy with clear intentions. Or it can be an uncertainty about the impact of the ongoing policies. Clearly, a definite plan has been put into action. In fact, Chidambaram did hint at it when he recently spoke to the country’s economic editors.

The FM said that if agriculture could grow by 4 per cent in 2008-09, compared to an annual average of less than 2 per cent in this century, India would achieve a double-digit growth in the overall economy. His comment is insightful for two reasons. One, he is banking on really high agricultural growth in the near future to achieve a robust GDP growth. Two, he probably feels that the rate of growth in other sectors, like manufacturing, may dip.

He’s partially right. All estimates, including by government and other think tanks, for the current year indicate that agriculture cannot grow by more than 3 per cent. They are convinced India’s economic growth will be lower than the 9.4 per cent achieved in 2006-07. Some say it may be less than 8 per cent, others a still vibrant 9.2 per cent. But no one is willing to bet on 9.5 or 10 per cent. "Yes, there will be a moderation in the pace at which the Indian economy has been growing," contends Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman, Planning Commission.

Some experts view the phenomenon in a more nuanced manner. C. Rangarajan, former RBI governor, and now head of the PM’s Economic Advisory Council (EAC), says that "there is some slowing down of the economy... if you wish to call it slowing down." Subir Gokarn, chief economist, Crisil, does not see the current scenario as a slowdown, and adds that "I would see it more as a moderation where 8.5-9 per cent growth is neither a shock nor a bad omen." Abheek Barua, chief economist, HDFC Bank, thinks that there is some "deflation in the euphoria about the Indian economy".

But what is crucial is that the slowdown or moderation is part of a deliberate exercise. It is part of a conscious economic roadmap charted out by the policymakers. It stems from a realisation that the economy is overheated. So, it is imperative to cool it down. It is the result of short-term decisions that seem to be working. It is a sign of a maturity where the government feels that it can deal with lower-than-achievable growth in the short run without hurting the long-term story.

So, what exactly are the government’s worries? How is it dealing with them? What have been the on-the-ground results and what are the long-term impact of these policies? A few months ago, the RBI thought India was entering into a high-growth, high-inflation phase. In economic jargon, it pointed to an overheating. In political lingo, it was suicidal with the state and national elections on the anvil.

To curb inflation, which is essentially the result of too much money chasing too few goods, it hiked interest rates. The idea was to suck out excess money from the system: higher rates would logically curtail borrowings, and also ease the zooming prices of assets like real estate. Since then, housing demand has eased and prices in Tier II cities have slumped. To cite an example, ICICI Bank’s home loan portfolio grew by just 30 per cent in 2006-07, compared to nearly 60 per cent in the previous year.

But the impact was more drastic in other sectors. In four-wheelers and two-wheelers, ICICI’s portfolio growth fell sharply. During April-June 2007, the auto sector and the two-wheelers segment witnessed negative growths compared to same period in 2006; although car sales were higher, companies like Tata Motors and Hyundai Motor showed modest growths. The same is the case with demand in other interest rate-sensitive areas like consumer durables. Says HDFC Bank’s Barua, "Some sectors are leading the deceleration. They have been affected, perhaps quite significantly." Adds Madan Sabnavis, economist, National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange, "The only worrisome feature is the growth in credit because it is a kind of proxy for what could be happening on the production front. After many years, we have seen a fall in outstanding banks’ credit." And Kaushal Sampat, coo, Dun & Bradstreet India, says that restrained demand due to tight monetary policies is responsible for the slowdown in the consumer durables segment.

Despite the negatives, firms are putting up a brave front. Says Ravinder Zutshi, deputy MD, Samsung India, "Normally the consumer electronics industry grows by about 8 per cent, but this year it is growing by about 12-15 per cent." Adds Girish V. Rao, VP (strategy and marketing), LG Electronics, "I don’t think the consumers are bothered, they are buying irrespective of the price." Only Gunjan Shrivastava, director (entertainment solutions), consumer electronics, Philips, admits that "what I anticipate is that if the slowdown continues for a longer period, volumes would be hit."

In the passenger car segment, major players are introducing special packages and schemes to boost volumes. Hyundai Motor recently launched its low interest (7.99 per cent) scheme as well sub-Rs 5,000 EMI for its largest-selling Santro. The schemes may be extended to other mass models like Getz. Similarly, Maruti Udyog’s MD Jagdish Khattar admits "it will be difficult to match last year’s growth", particularly the 35 per cent growth in compact cars "is out of the question" because of the base effect. Maruti has started new initiatives, some of them targeted at rural areas and village panchayats.

This enthusiasm is not visible when it comes to corporate earnings. A July report by Citigroup states that future earnings growth will be "less spectacular". The reasons it cited were "limited levers for margin expansion" and "moderating credit growth". A study by Macquarie Research pointed out that higher interest rates will "lead to volume decline" in the auto sector, which will also witness lower profitability due to margin squeeze, harsh competitive landscape, and rising raw material costs.

Everyone, however, is waiting to see the impact of high interest on future investments, both in the public and private projects. At present, the jury is still out on this issue. Says Gajendra Haldea, advisor, Planning Commission, "At a macro level, if interest rates go up, theoretically there could be some slowing down on investments. But at the project level, the impact is difficult to quantify. I don’t think we are in such a high interest scenario where we should have a fear of investment levels going down." Others feel the same way. "High rate of interest and therefore high cost of capital is bound to affect investments but how significant is the effect is not yet clear," says Shashank Bhide of NCAER. "People don’t invest looking at the investment rate today but at the profitability. So even if there is zero interest rate people will not invest unless there is profitability. The investment rate has risen from 25 per cent five years ago to 35.6 per cent now," explains Saumitra Chaudhuri, economist and an EAC member.

But there are a few contrarion views. Pai Panandikar of RPG Foundation says that although "there continues to be an increase in investments mainly due to company profits being very high, leading to a ploughback of profits," the situation can change dramatically if RBI further hikes interest rates. P.S. Bami, president, India Energy Forum, is more vocal: "Definitely it (high interest rate) is having an impact on capitalisation. If you have to be competitive, the rates have to be lower." When you look at the situation on the ground, there are already delays in infrastructure-related projects. "At this moment, it is hitting the small and medium enterprises. For them, projects whose viability had been calculated at lower interest rates have suddenly become unviable. Very soon, the same situation would cross over to the larger enterprises," explains Amit Mitra, secretary general, FICCI.

Lizzie Jacob, chief secretary, Kerala, feels that although "projects may not be impacted straightaway, but the effect will be seen after a little gap." But she admits that costs have gone up for road projects. In the case of public-private partnerships, the companies are seeking bigger government share which, in turn, implies that the state government will have to borrow from external sources and its debt burden will zoom. In addition, says Rakesh Nath, chairperson, Central Electricity Authority, "The tariff rates will go up. Ultimately the consumer will have to pay more for power."

Hyundai automobile plant in Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu

Still, there is a section that thinks the interest rate issue is a bogey and should not be taken seriously. Haldea says that the current scenario is different from the past era, where everything was cost plus. Thus, in the past, higher interest rates meant higher costs. "In a competitive market, some of these costs could be absorbed by the investors," he adds. According to C. Rangarajan, interest rates cannot be looked at in isolation. "If the expected growth rate is 9 per cent and it can be sustained over years, than you can have high rate without any adverse impact. The same rate is unsustainable when the economy is growing at 3.5-4 per cent. When South Korea was growing rapidly, the real interest rate was 7 per cent."

One will have to wait a while to see the exact impact of the high real interest rates. But the effect of another policy that the RBI deliberately pursued is clearly showing. The central bank allowed the rupee to strengthen against the dollar to stem the inflows of foreign money, yet again to control inflation. In the past one year, the rupee has gained 11 per cent against the dollar, and the figure for pound and yen is slightly lower. Expectedly, this has hurt exporters where it matters the most.

A knitwear unit in Tiruppur

According to a FICCI study, in sectors like pharma, textiles and processed food, exports turnover is down 10-40 per cent, while realisations have fallen by 6-15 per cent. In other areas like machinery, handicrafts and electronics and electricals, the turnover is expected to fall steeply by 25-50 per cent. Admits a cautious Gopal K. Pillai, commerce secretary, "Expect some hit in the second quarters, as witnessed in the first one. We are still looking at 18-20 per cent growth, though it is lower than earlier expectations." The best way to illustrate what’s happening is through an exporter. Meet Mukhtarul Amin, CMD, Superhouse Ltd, a leading leather footwear exporter. He says, "shipments have been going at a loss, and some firms are in the process of laying off labour". Superhouse postponed its plans to set up two new factories and raise production capacity by 10,000 pairs a day. But last week, the government announced a relief package for small and medium exporters and some select sectors by reducing interest rates for pre-and post-shipment. "With the new incentives, we propose to go ahead with our plans," he explains.

But Amin categorically says that this relief package is "at best, a bridge solution. The government will have to take more steps". In fact, Superhouse is furiously trying a two-pronged strategy to combat the negative influence of the rising rupee. It is cutting costs wherever possible, finding ways to absorb price increases, and getting into more value-added products by putting more efforts in the designing part of the footwear. "In the case of fashion-based products, the impact was not much," contends Amin.

Auto credit has hit a roadblock. Automakers are luring customers with easy deals

As the grand economic strategy shaped by Chidambaram, Reddy & Co becomes clearer, and its combined impact becomes more visible, there are two opposing camps that have been formed on the implications of this deliberate cooling down of the Indian economy. One says that there is no other way out except to reduce interest rates, and either give more incentives to exporters or let the rupee slide a bit. Even Arvind Panagriya of Columbia University wonders "whether growth will decelerate in the next few years," since reforms are on the backburner.

On the other side is Ahluwalia, who thinks that thanks to the current policies, the fears of overheating are things of the past and inflation has steadily declined. "The monetary tightening has achieved the objective that was expected and I don’t think it has really killed the growth momentum," he adds. According to Shankar Sharma, joint MD, Angel Broking, "Even if we slow down to 8.5-9 per cent, heavens will not fall". And Gokarn concludes that "the current slack is actually good for the industry and country instead of hurtling towards a breakneck growth rate that was largely unsustainable."