It was in 2004 that Karan Bali, a filmmaker, first came to know of Ellis R. Dungan. “Just the thought of an American making Tamil films, that too in the 1930s, was enough to excite me,” he says. “It felt too good to be true.” But Bali, who was at the time researching for upperstall.com, his Indian cinema website let his excitement remain confined to writing an article on the man who came to India for six months in 1935, went on to stay in the country for 15 years, and made 11 Tamil feature films without understanding a word of the language.

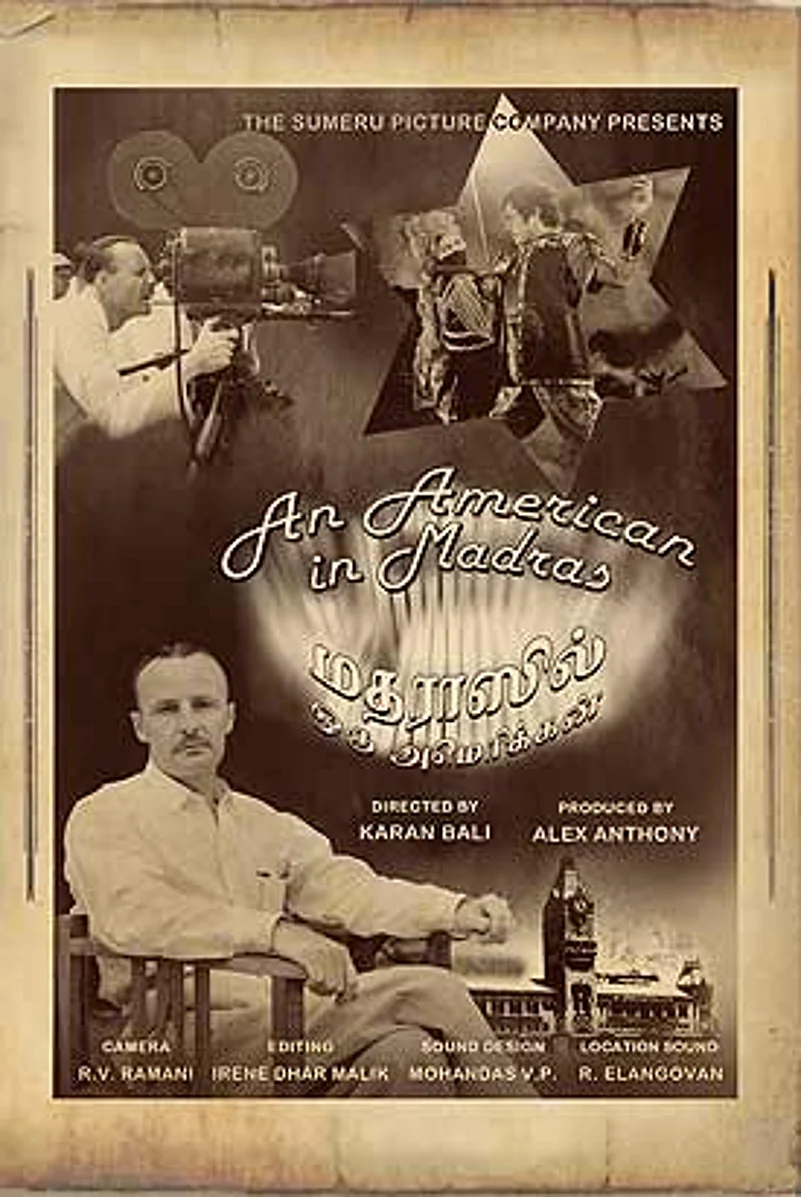

Much later, he read Dungan’s autobiography and saw four of his available films—Ambikapathy, Meera, Ponmudi and Mantri Kumari. He then decided that Dungan merited more than a few thousand words. “Dungan’s contribution to Indian cinema may have been immense, but his name hasn’t travelled beyond historians and hardcore buffs,” says Bali. His documentary, An American in Madras, tries to set right this imbalance, opening up Dungan’s life to ordinary viewers. The film played on February 6 at the Mumbai International Film Festival for Documentary, Short and Animation Films.

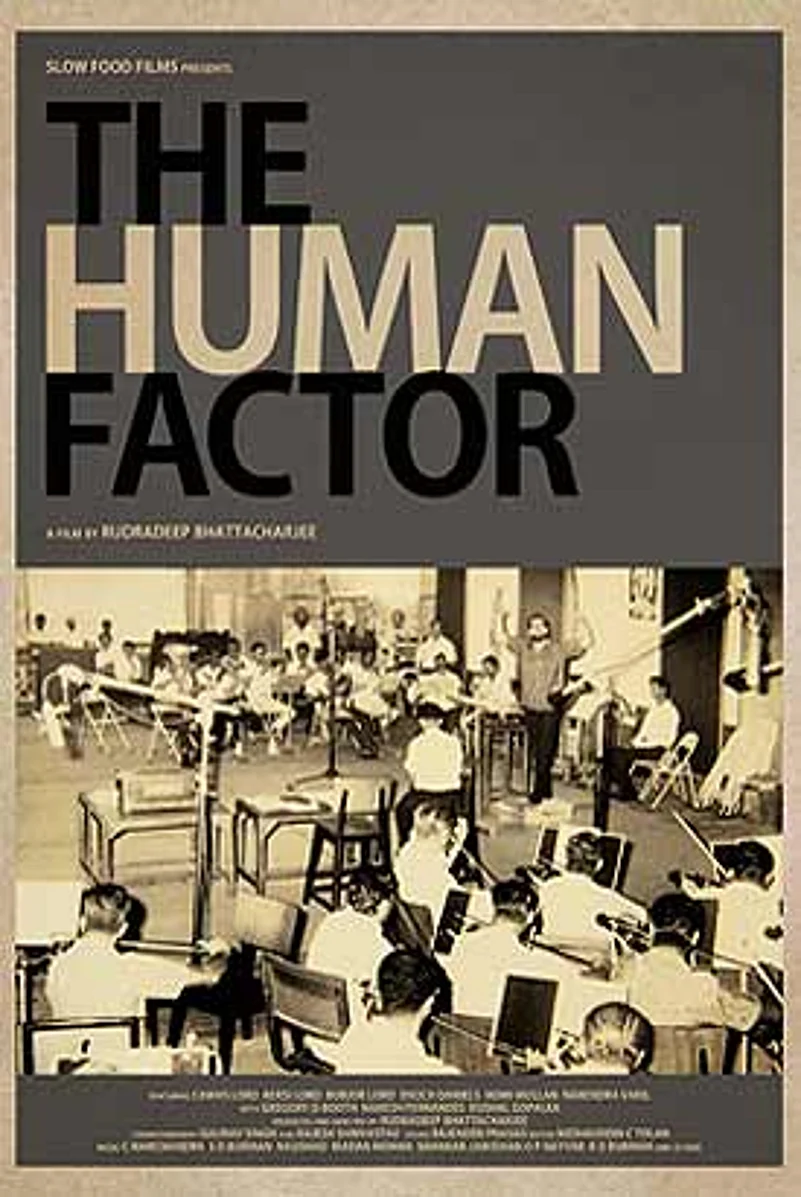

Rudradeep Bhattacharjee attempts something similar in The Human Factor, focusing on the little known Lord family of musicians and arrangers: father Cawas and sons Kersi and Burjor, whose art and craft touched some of the most celebrated songs of their time. It was Kersi who played the cigarette lighter refrain on the glockenspiel in Main zindagi ka saath nibhata chala gaya from Hum Dono. It was him again who devised the delightful conversation between the khol and the Chinese temple block in Jaane kya tune kahi from Pyasa. “Ten minutes of meeting the family and I knew there was an interesting film lurking there,” says Bhattacharjee. The Human Factor tells how the Lords “crafted bridges between the verses and the chorus”, composed incidental music and did the so-called dirty work for the composers. They never got due place, not even in the credits.

These two documentaries aren’t the only ones turning the movie camera on to Indian cinema. Kamal Swaroop’s Rangbhoomi, which premiered at the Rome Film Festival in November last year, looks at the years (1920-22) that Dadasaheb Phalke took a break from filmmaking to live in Varanasi and write the eponymous play. And Jaideep Varma, who made the excellent Leaving Home on the band Indian Ocean, takes an unlikely up-close-and-personal look at the life and times of filmmaker Sudhir Mishra in Baavra Mann.

| Pan shot Posters of documentaries on Dungan and the musical Lords | |

Why Sudhir Mishra? It’s a question Varma has often faced. “Why not Shyam Benegal, for that matter, I’ve been asked,” he says. But his idea was to zoom in on a maverick, “uncelebrated” filmmaker who’d not been able to fulfil his own potential. As Naseeruddin Shah says of Mishra, “he hasn’t made the definitive film yet”.

“Sudhir is obviously talented, always bright,” says Varma. “But he himself admits he hasn’t lived up to his own promise. Making a film on an individual is not just about hailing him or talking about his grand successes. It’s about being human, looking at someone with all their flaws.” Despite that, Varma confesses, Mishra at his best is a filmmaker he enjoys watching. “He handles the personal with a lightness of touch. I admire his Hazaron Khwahishen Aisi and Khoya Khoya Chand,” he says. Mishra fan that he is, Varma looked at his own docu as akin to a hobby rather than a project, working on weekends over one-and-a-half years.

The deeper tie between these films is that they go beyond the personal to cast an eye on cinematic history. Bali’s film does mention the tumultuous marriage of Dungan—the reason why he had to head back to America—but it is more about what he brought to Indian cinema. “His cinematic language was much more evolved, and yet nowhere did it feel that the films had been directed by an outsider,” says Bali. Dungan brought in professionalism, technical innovations—right from shot division to the use of Dungan tracks and trolleys for indoor shoots. He also introduced Max Factor make-up for artistes. The American touch showed in his portrayal of gender equations. “It’s the woman who takes the initiative in love in Ponmudi—a woman who is bold, proactive and in control of her fate,” says Bali.

Varma calls his work a collaboration with Mishra. “I’d told Sudhir to get as candid as he could.” Sudhir has obliged, speaking on his relationship with his late brother Sudhanshu and partner Renu Saluja. In his reminiscences of them, there’s an inexplicable touch of guilt. But Sudhir’s story is also the story of the parallel cinema of the 1970-80s, its idealism, rebellion and dissent; the fun they had as they struggled; the promises they belied; the dry didacticism that might have killed it.

“It’s the cinema that influenced me a great deal. It shaped many filmmakers but no one has paid tribute,” says Varma. On a larger level, it’s also about the cultural milieu of the time and its decline, about how it’s getting difficult to make a good film when the be-all and end-all is the urge to market and entertain.

For Bhattacharjee’s film on the Lords, the trigger was a book by Gregory Booth called Behind the Curtain. “I wanted to make a film on the rise and demise of the orchestra in Hindi cinema, and when I met the Lords I realised it would be best to tell the story through them,” he says. It was in 2010 that he read the book. Two years later, he got down to making the film.

At one level, it’s about the disillusionment of the Lords with the industry. At another, it’s about evolving music trends—how Hindi cinema embraced jazz, Latin American and Spanish rhythms, how that led to the introduction of a range of instruments and sophistication in orchestration. It is about music-making, how the human element lent it soul and how, with the rise of electronic music, it’s become a “spare parts assembly line technique”.

It is about how the pursuit of a better music led to the collapse of an established system, instruments getting phased out and the synthesiser becoming the altar. But the film doesn’t diss technology, rather accepting it as a march of time. “After all, had it not been for the digital Canon 7D camera, I’d have never been able to gather enough resources to make the film,” says Bhattacharjee, who self-funded his project.